Among the biggest vehicles on the road—and working in the most severe conditions—Class 8 collection trucks are everywhere, from busy urban centers to rural residential neighborhoods—and yet, most people pay them scant attention. Nevertheless, these “unseen” civic workhorses have evolved: Collecting garbage is not the simple task it once was, and technology in the refuse collection industry has not remained stagnant.

For centuries, simple wagons sufficed. Trucks were introduced in the automotive age, with open-top dump trucks becoming commonplace 100 years ago. Because they were not specifically designed for the refuse industry, these adapted haulers were rife with flies and vermin, wafting trails of heavy of stench from spoilage and decay in their wakes. To combat the malodorous neighborhood invasion, covered-body trucks had been designed by the 1920s to handle the odoriferous task.

In 1937 George Dempster invented the Dempster-Dumpster system that involved mechanically tipping waste containers into the collection vehicle. This improved speed and safety. One year later, a hydraulic compactor was added, doubling a truck’s capacity. In the mid-1950s the first front loader was introduced.

Change and innovation didn’t stop there, particularly in response to encroaching emissions regulations, federal highway laws, and the rigors of the job. “It is the most severe service vehicle on the road,” claims Mark Neale, director of application engineering for Autocar, based in Hagerstown, IN. Comparing the refuse truck with another large, urban civic vehicle, the city bus, he says the collection vehicle is roughly double the weight of a bus at 50,000 to 60,000 pounds and stops more often, with an average of 1,500 stops per day.

Although the collection-vehicle industry poses some unique and demanding requirements, it does not have sufficient volume to dictate design criteria. “It’s a small market,” Neale notes. Out of approximately 250,000 Class 8 trucks produced annually, refuse trucks comprise only about 6,000 to 7,000. “It’s all about economies of scale, and a small market means compromise.” Nevertheless, just as garbage trucks were adapted for their dirty duty 100 years ago, so too are they now, taking advantage of automotive advancements in design, engineering, and technology.

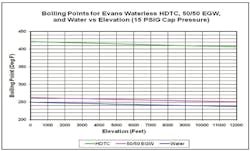

Waterless Coolant Veolia Environmental Services has been conducting a yearlong fuel economy test with Evans Cooling Systems since September 2009. The test involves using Evans’ waterless engine coolant, along with higher temperature thermostats and elevated fan-on temperatures. A 2006 Mack MR688S was retrofitted with Evans waterless coolant (HDTC), a 215 thermostat, and a resistorpac to elevate the fan on temperature. Fan temperatures can be safely increased to 230°F, reducing the fan-on time, often by as much as 50%. Over the course of the past year, results have shown fuel savings up to 4.75%.Dan Cowher, fleet director at Veolia, says, “In our year-long evaluation, we’ve seen that Evans waterless coolant allows fuel saving strategies with elevated temperatures. Results have shown improved fuel economy month after month since the test began with Evans.”Keeping an engine cool in severe duty applications consumes a lot of fuel. Radiator fans for heavy-duty engines draw considerable horsepower, particularly in refuse trucks that repeatedly start and stop and operate in circumstances that lack ram air. Consequently, the fan engages frequently, consuming energy and fuel. The energy that it takes to maintain coolant temperatures below the boiling point of water can be a huge waste of fuel. Any reduction of fan-on time will decrease fuel consumption.

The SAE Type II Fuel Consumption Test was recently conducted using Evans waterless coolant and 215°F thermostats, demonstrated a fuel economy improvement of 3.04%. The fans of both the test truck and the control truck were locked 100% “on” in order to eliminate the fan as a variable. The improvement in fuel economy from using 215°F thermostats is in addition to savings are obtained by increasing the fan temperature to 230°F.

Evans waterless coolant boils at 375°F, creating a huge separation between the operating temperature of the coolant and its boiling point. Metal temperatures can be controlled at coolant temperatures above the boiling point of water, allowing fan-on temperatures to be safely increased. By removing the boiling point barrier, fuel saving strategies not previously achievable can be employed with waterless coolants.

Gas and Go

A recent study by Transport Canada estimated the North American urban refuse fleet at 200,000 vehicles. Those refuse trucks use 1 billion gallons of diesel fuel annually, representing 3% of the US’s total diesel fuel consumption. About five years ago, the Environmental Protection Agency identified trash trucks as one of the top 10 polluters. Contributing factors were diesel engines and stop-and-go driving. With increasing fuel costs and growing concern for the environment, demand is building for cleaner, quieter, more energy-efficient collection vehicles.

Because refuse trucks are making the rounds every day of the week, a clean-burning, economical fuel can benefit both a municipal budget and the environment. With the average price of natural gas as much as $1 per gallon less than diesel, according to Clean Energy, the number of municipalities and refuse haulers operating natural-gas vehicles has been increasing nationwide since 1998, when Waste Management paved the way in California.

The trend is definitely going away from diesel, insists Marc Nadeau, product manager for the Labrie Environmental Group, in St. Nicolas, QC. Labrie, a top tier manufacturer of equipment for the solid waste industry in North America, has been working with compressed-natural-gas (CNG) trucks since 2001. As the first manufacturer of its kind to obtain ISO 9001-2000 certification (in 1999), Labrie has developed standard-setting technology through design by investing heavily in research and development to offer greener, more efficient, smarter, and safer equipment.

Compressed natural gas is the choice prompted by what Nadeau calls “big reserves of natural gas in the US and Canada,” adding that “the trend in that direction is for cleaner engines.” Considered the cleanest fuel currently available, natural gas reduces smog-causing nitrogen-oxide emissions by more than 80% and reduces greenhouse gas emissions by 10% to 15%, compared with diesel-powered vehicles. Natural-gas vehicles are also 90% quieter than their diesel counterparts, a benefit in urban communities where noise pollution is a growing concern.

Cleaner fuel helps the engines last longer. It’s one reason Kevin Watje, president and chief executive officer of Wayne Engineering in Cedar Falls, IA, thinks CNG was adopted early. Another reason for acceptance is because the fuel is cheaper—especially when companies take advantage of fixed-price, multiyear fueling contracts. Diesel trucks are more expensive, thanks in part to the add-ons required to meet 2007 emission standards established by the EPA. Those costs will continue to increase, with additional add-ons needed to meet the more rigorous 2010 EPA emissions standards.

Natural gas is also more easily accessible, contends Matthew Walter, director of product management, and Jeff Swertfeger, director of marketing communications, with McNeilus Truck and Manufacturing, based in Dodge Center, MN. “CNG is the winner for the refuge market because of the difference in infrastructure,” Walter believes. “It’s off-the-shelf, easy-to-maintain technology. If you have a natural-gas line, you’re a good candidate.”

CNG is supplied through a pipe in the ground. Liquefied natural gas (LNG), on the other hand, requires a third party to manufacture and deliver it: There is no way to manufacture it onsite, Walter insists. Furthermore, it requires someone wearing protective equipment to fill the tank, whereas the driver of a CNG vehicle can refuel. Another complication of LNG is that it must be stored at a temperature of –260°F and will “vent off” when the vehicle is parked at night. “For vocational use, where trucks fuel at the same location, the economics work better for CNG,” Walter summarizes.

McNeilus believes so strongly in CNG that the manufacturer now designs and installs the system. “If you order a body, chassis, and fuel system, we install, test, and deliver it,” Walter states. “It’s turnkey.” It preserves what Swertfeger describes as the chain of custody and reduces lead time on orders. Traditionally, with natural-gas vehicles, the chassis manufacturer installs the engine but not the fuel tanks, because they mount to the body, not the chassis. “Body and chassis companies have non-running vehicles,” Walter details. “It’s a cumbersome process, with the components going back and forth in a loop, shipping from one manufacturer to another. It gets expensive.”

The economics work out better, Walter believes, if McNeilus installs the CNG infrastructure, piggybacking on the technology of buses by mounting the tanks on the otherwise unused roof area. “It’s not difficult or cumbersome. The fuel-system pressure test is done here. It cuts shipping costs.”

Getting Rid of Gas Pains

The natural-gas engine is as productive and reliable as the diesel now, Neale says, thanks to a lot of research and development over the last 10 years that led to improvements. California was the pioneer, he claims, but now all manufacturers are willing to get involved.

One reason many are willing to get involved stems from federal tax credits of up to $32,000 per heavy-duty truck, making natural-gas trucks even more economical and helping ramp up production. The financial incentives help offset the upfront investment, which Ken Beaver, director of marketing for Heil Co., says more municipalities seem willing to make for the relatively clean, domestic source of fuel. And, because vehicles achieve better fuel economy when using CNG, there’s some payback.

Neale thinks the same concessions should be granted to other emerging fuel technologies. “Natural gas provides a 30% reduction in carbon emissions. If you get 40% reduction in fuel [with other sources], you will have a cleaner vehicle than with natural gas. The government should reward that technology. Asking people to commit to new technology is expensive.”

Autocar, the largest builder of natural-gas vehicles, is committing by developing trucks powered by alternative fuels. Neale says the tax credit could help, noting that a $1,200 credit on hybrids has expired. Because the components are still made in low volume, prices are high, he complains, and without tax credits and incentives from the government, interest in hybrids lags.

Although there are tax incentives with CNG, Walter believes hybrids play an important role. “Alternative fuels and hybrids reduce our carbon footprint.” That’s why, Nadeau says, the customer is looking at alternative energy. The problem, as Walter sees it, is twofold: economic and familiarity. “Natural-gas technology has been in place 20 years; the hybrid is a new realm.” As Swertfeger interjects, there’s an element of “technology anxiety.” The modified diesel engine used for CNG is familiar, while hybrid technology is still in the prototype phase. However, Walter concludes, the price premium is the hardest hurdle to overcome. “Economics dictate the market. It’s all about return on investment—and hybrids aren’t cutting it.”

That’s subject to change. Autocar has been working on hybrid technology for five years. “The Xpeditor is still in its infancy,” Neale says of the company showcase vehicle. “It takes a lot of development work.” Driving interest in hybrids are issues such as fuel consumption, cost, the stop-and-start urban work environment and 10 years of pressure from the EPA on nitrogen oxide and particulates.

On urban collection routes, refuse trucks can make up to 150 stops per hour, which places a heavy load on the powertrain and results in low fuel efficiency and high emissions. Hybrid powertrains are known to perform well in such conditions, especially when designed specifically to meet the needs of the duty cycle of a collection vehicle, which consists of collection for 76% of the time, transfers between depot, route, and landfill for 20% of the time, and unloading for the remaining 4% of the time, per Transport Canada. Most of the fuel is consumed during collection, when the vehicle is less efficient because it’s operating the hydraulics. The amount of fuel necessary to generate hydraulic power represents 40% of the total fuel consumed in collection mode. Hybrids also provide a significant reduction of exhaust gas emissions.

While electric hybrids are common in Europe, they aren’t used much in the US. “Electrical systems don’t have the capability of absorbing energy quickly,” Neale explains. “They have limited energy recapture ability, so they offer limited assistance.” Because there is so much mass to stop and start, a lot of energy must be captured quickly. Batteries are incapable of capturing a large amount of energy quickly and efficiently.”

In addition, battery systems are bulky and heavy. “You have to find real estate on the truck for batteries,” Neale says, and because batteries are heavy, there are issues with weight distribution. Attention has become focused on weight reduction and distribution in light of the awareness of the benefit of running the vehicle at a lower tare weight chassis. “Safety and fuel are driving the resurgence of interest in lighter weight.”

Manufacturers are making pieces lightweight but strong in the ongoing battle to save weight without compromising the integrity of the vehicle. However, an unfortunate side effect of the emissions regulations is that the weight has gone up about 100 pounds. As Neale details, with federal bridge law limiting weights to 51,000 pounds, a chassis weighing 40,000 pounds empty doesn’t leave much latitude to carry a lot. Reducing chassis weight to 30,000 pounds substantially increases payload.

The weight of the batteries has to be accommodated, Watje points out, and battery life is limited. “We talked to OEMs,” he says. “They believe the best economic option is the hybrid hydraulic. The price is better and fuel economy is better than with alternative fuels. It can reduce our dependency on oil. That shifts the focus. It’s a paradigm shift.”

Fuel consumption cannot come at the cost of productivity. As Watje says, you have to find the sweet spot between fuel consumption and output ratio. That’s why Nadeau believes the hybrid trend isn’t headed toward electric, which is heavy and inefficient, but rather to hydraulic hybrids that use the energy from braking for acceleration and other functions. “It’s an expensive system,” he says, “but you can save 20% to 40% in fuel costs.”

The Transport Canada survey concluded that lower cost and simpler implementation of the hydraulic hybrids can mean a payback time shorter than that of electric systems. Hydraulic components are available because the vehicles already use hydraulic systems and maintenance is familiar. That’s why Autocar is pursuing a hybrid hydraulic option, which, Neale estimates, could reduce fuel consumption by as much as 30% to 50%.

With six field trials under way, Autocar is almost ready for full commercial launch of its hydraulic hybrid. Neale elaborates on the different philosophies exemplified by the two systems, parallel and series. “Parallel systems are mild, less complex,” he says. “They offer less in the way of fuel savings. Series systems have a capacitor. Super capacitors have unlimited ability, but also unlimited cost. There is more potential for fuel and emissions savings, but it takes longer to develop and is very expensive.”

As manufacturers rush to perfect the technology of hybrid systems, the EPA struggles to come to terms with how to rate them. “It’s a challenge to figure out how to rate various systems when manufacturing [of components] is separate,” Neale postulates. The industry creates a shared product, he explains, with separate manufacturers for cab, chassis, and body. Autocar, 90% of whose business comes from the refuse market, tailors its chassis for the body because it believes it’s important not to modify the chassis. Providing integrated packages speeds through time during manufacture, making the vehicle more efficient and cost effective.

But because the industry is shared, rating the efficiency of hybrids will be a challenge. “There are a lot of potential combinations of components and overall weight,” Neale ponders. “There’s a huge swing in the economy of application between 1 and 5 miles per gallon, depending on the chassis and body.”

Innovation Is Crucial

Product and service innovation is the driving force for continued growth in every industry served by Fontaine Modification. It begins with input from the vocational truck operator, develops momentum with the truck’s original equipment manufacturer and component suppliers, and rapidly moves to prototyping and certification testing to meet mandated requirements. All product development takes place at Fontaine’s dedicated Innovation Center in Charlotte, NC, rather than in a production environment. This approach ensures excellence in design, product safety, and consistent product output upon product release.

Fontaine’s Innovation Team consists of representatives of engineering, production, sales, field operations, and senior management. The team meets weekly to assess current innovation activities, evaluate input from the innovation model, and continually push the envelope to keep moving forward.

“The members of the innovation team cross over all aspects of the business. They are in position to give us input from our key customers and the daily operators of our products to the technicians on our production floor,” says Will Trantham, president. “This brings real information to the team, and allows us to move quickly to meet the needs of the industries that we serve. Agility is key when reacting to market trends and future product requirements.”

Innovations under development in refuse collection vehicles include improvements in product longevity, weight reduction, production process cost improvements, and innovative operator control designs.

The use of composite-based materials is just one area under development by Fontaine engineers. These materials reduce the overall weight of a product, increase longevity when compared with traditional carbon-metal materials, and allow for improved production processes, all of which increases efficiency in manufacturing and reduces overall costs to the end user. Operator safety, the operator’s interface with the chassis, and bodywork controls are also quickly evolving areas of innovative ideas that are at the forefront of development.

“At Fontaine, we are dedicated to continually improving the operating relationship between the driver/operator and the truck chassis,” Trantham says. “Today’s vocational truck users must be able to improve task efficiencies, increase productivity, and substantiate their company’s value proposition while operating in the safest and greenest environment possible. Being the provider that meets those core values day-in and day-out is what drives us as a company. The commitment to green innovations has gained significant momentum within Fontaine and its core product groups. While CNG engine installation and CNG/LNG fuel delivery system installations have been core to our business for several years, recent innovations in hybrid-electric and hydraulic assist designs are being incorporated into our production and work processes to meet our customers’ demand in those areas. Electric, hybrid, and diesel-fired auxiliary power units to reduce the effects on the environment by limiting truck idle times are included in the green innovation processes as well at Fontaine Modification.”

Paybacks Don’t Have to Be Hell

Efficiency is driving change in the industry. “Everyone is looking at their numbers,” Nadeau says. “If the return on investment is two to three years, that’s good.” As more cities struggle with lower tax revenue, cost becomes a major factor in purchase decisions. Different perspectives create different criteria for purchases. “A lot of customers are focused on [purchase] price,” Neale speculates. “Others look at life cycle cost; they’re buying more premium options.”

Cost consciousness has changed the construction of the truck, particularly in locales where recycling is prevalent. Labrie has adapted to changes in the market, Nadeau points out, by using higher strength, weather-resistant steel in its construction. “More resistant steel increases the life of the truck,” he states. “Glass wears steel faster.” Using a better grade of steel can result in fewer repairs, less downtime, and longer life, without added weight. In fact, it can even lower the weight of the vehicle, because stronger steel can be thinner.

High-tech alloys add strength without weight. Wayne Engineering uses a Swedish steel called Hardox because its shape memory makes it more resistant to deformation and abrasion. Whatever material is chosen, Watje says it needs to be abrasion-resistant, resilient, and strong. But no matter how good the steel is, he says, Wayne uses as little of it as possible. “Engineering has changed. We’re rethinking how we engineer, and we’re creating lean designs. We rationalize every part and piece that goes into the vehicle. We look at it from a DOT standpoint and try to get more payload.” Weight reduction is an ongoing battle, he says, and now pollution reduction has to be balanced with economic feasibility.

Reducing weight without reducing capacity increases load, Beaver summarizes. He says Heil’s Half/Pack is 4,000 pounds lighter than the standard equivalent and features overload control to track the weight of cumulative trash picked up. It stops loading when the limit is reached. Overweight vehicles lead to tickets and fines, reduced lifetime, increased brake and tire wear, and decreased fuel mileage.

Changes in the emissions regulations have caused weight gain for all chassis, Walter complains. Payload is on everyone’s mind. “It’s the eternal quest: more freight, less weight.” McNeilus is trying to do more with less, he states: the same life cycle for the same price. To do that, the company has to design to reduce weight where it won’t compromise performance. Elements are designed to be lighter, using exotic alloys of steel and composites. “Our new designs for efficiency are better than cutting weight.”

Walter also credits access to deep resources with McNeilus’s parent company, Oshkosh, and connections to key suppliers, keeping McNeilus from being at the mercy of the fluctuating steel market. “We challenge our suppliers to lower costs,” he says. Another Oshkosh resource is the on-staff metallurgist, who understands the molecular level of steel grade and keeps in mind the total life cycle of the unit when specifying materials. “We use a proprietary recipe on steel, raising certain components for longer life in certain applications for more bending force or corrosion resistance.”

The overall structure of the collection vehicle has changed, in construction and in materials. Fifteen years ago the sidewalls were straight, Walter points out. Now the bodies are curved, rounded. “We’re taking that into the internals now,” he says. Bodies have gone from a flat (sheer) to a curved face because the curve adds tension, making the body stronger, yet lighter.

Disc brakes, common in Europe, can also save weight on the truck: as much as 500 to 700 pounds, Nadeau says. “But they cost more.” However, he adds, “you need to think of the total operational cost over 10 years.” He claims disc brakes allow operators to collect more because they brake faster and better, and, since time is money, it all adds up. They’re coming to America, he believes. In fact, some of the “big” customers are already using them.

Another time- and money-saving feature is automation. “With an automated truck, a driver can pick up 800 to 1,000 homes a day,” Nadeau estimates. “With a rear loader, only about 600.” The drawback, he says, is cost, up front and operational. The components are small and more complex and require a mechanic to maintain. However, he believes automated trucks should last about 10 years and amortize rapidly.

Customers have different time frames to amortize. Municipalities, large national fleets, and private companies have different criteria. The challenge for all of them is payback, Neale recognizes, “but reduction in maintenance and extension of life can pay off.” You have to be competitive on cost, he admits, but lighter weight, reliable performance, and ease of maintenance contribute to reducing operational costs.

Thanks to higher efficiency through automation, Watje says, the top 10 major haulers make more money. “They can pick up more trash with less labor.” One of the basic principles in the industry decrees that some costs are fixed. Capital costs—the trucks—are unavoidable. Fuel is a necessity. But labor provides the biggest opportunity for reducing expense. Reducing the cost of labor contributes to a faster return on investment for an automated truck.

Specialized trucks can improve more than just efficiency. Labrie’s split-body collection vehicle is popular in areas such as California and the East Coast, where multiple types of collection can be performed simultaneously. “In Ontario, we offer a new tipper to collect kitchen bins separately but at the same time as garbage,” Nadeau explains. In addition to food waste, bottles, paper, and fiber can be separated out.

Depending on the density, Nadeau continues, specialized trucks can save on tire and brake wear, not to mention fuel and man-hours. As an added bonus for recycling, some cities are issuing rebates and coupons. “A lot of cities recycle so they have less garbage going to the landfills.”

Environmental and regulatory issues are changing how waste is collected and transported, and every municipality has a different set of guidelines. The challenge, as Beaver sees it, is to build a body capable of handling segregated wastestreams. Keeping costs in line, Heil manufactures uniquely configured vehicles from standard components.

Keeping ’Em (Safely) in the Cab

Many money-saving designs are also safety features. Disc brakes, for example, shorten stopping distances, which makes collection vehicles safer. Neale says this is the industry’s third attempt at making disc brakes work and that the newer, heavier, more durable design shows promise.

One of the biggest safety moves, Nadeau insists, is keeping the drivers in the trucks by opting for hydraulically automated vehicles. “It keeps drivers in their seats with their seatbelts on. It saves injuries.” It saves lives—Nadeau recounts statistics that report 40 deaths a year in the refuse collection industry. It also saves time—it’s much faster for a driver to operate hydraulic controls to lift and dump heavy loads than it is for the driver to get out and manually dump the receptacles into the truck.

Automated trucks have been around for about 15 years. They’re the flagship for Wayne Engineering, which remains one of the longest-running automated truck companies in the industry. “The general consensus is that everyone will go to automated,” Watje predicts. Rear loaders will never completely go away; however, they will be reserved for special circumstances, such as hard-to-deal-with situations like disasters and construction demolition.

But rear loaders are often rear-ended, Swertfeger says. Because McNeilus considers safety to be a quintessential component, the company has taken a leadership role to educate the public, participating in a “slow down to get around” campaign with the DOT and OSHA. “Garbage trucks are in harm’s way every day,” Walter states. “They’re an invisible vehicle on the road.”

Drivers may look past garbage trucks, but a collection vehicle operator should be able to see everyone else on the road. EPA regulations in 2007 spurred modifications that increased the hood height…and decreased visibility. Nadeau says there’s even more behind the cab in 2010, meaning even less visibility. To offset the problem, he says, manufacturers are installing bigger mirrors and haulers are adding camera systems. “Visibility is a huge safety issue,” Neale affirms. “We package components to not impede visibility.” Illuminated and integrated body controls are easier to see and reach.

Safety isn’t the only influence affecting change. Market forces are driving this kind of design change, insinuates Walter. The need to be more productive—more efficient—is one of the biggest reasons for the move from two men at the rear to one-man, automated technology.

Historically, collection vehicles have proved a harsh environment, with dust, noise, vibration, exposure to the elements, and odors. Improved HVAC systems help separate the harsh exterior environment and make the interior one more comfortable—enticing operators to stay safely inside. “Drivers spend a lot of time in the cab,” Neale summarizes. “To keep a stable work force, haulers must improve the environment for drivers. It’s becoming more important.”

Nadeau concurs. “There’s big interest in ergonomics,” he says. For a Toronto application, Labrie modified the joystick support for more flexibility because, as Nadeau explains, people come in different sizes and the modification offers more range. The “Labrie console” has cleaned up the dash. The big black box typically in the center of the truck has been moved to the back, leaving only the buttons on the dash, for a cleaner look. Not merely aesthetic, it moves the driver closer to the joystick, so the operators don’t move their hands as much, reducing fatigue.

People are getting bigger, Neale says. Although he says most cabs are a “mature design,” tilt steering and reclining seats are relatively new features to accommodate operators of different—or increasing—sizes. Autocar lowered the cab to make getting in and out easier. “There is more emphasis on operator comfort in the specifications,” he says. “It’s not all about the lowest cost of production.”

Noise levels, a real factor in fatigue that has been addressed by OSHA regulations, have been lowered through the incorporation of multispeed fans and sound deadening. Trucks are so much quieter, Walter half-jokingly says, people now complain about squeaky brakes.

In all seriousness, he says ergonomics have become a critical aspect of design, and the reality of operator habits must be taken into consideration.

For example, the new McNeilus control systems are resistant to Mountain Dew, Walter points out, and the new ZR series side loader has an arm that operates in a very soft, cushioned and controlled manner. “It doesn’t rock the cabs, which leads to operator fatigue.” It’s also easier on the street and the shocks, prolonging the life of the machine. It can go faster, enhancing productivity, and more safely. “It’s a productivity win-win.”

Technology Now and Forever

“It’s not a static industry,” Walter points out. “It’s changing all the time.” Behind those changes are regulatory mandates, demand for increased efficiency and productivity and the advancement of technology. For nearly every challenge faced by these rugged workhorses, technology has an answer intended to make life easier.

Labrie offers an electronic module to operate various functions of the truck, such as auto dumping or the fork. But electronics goes beyond the mechanical. A couple of years ago, onboard scales were added to front loaders, allowing operators to weigh containers at each stop. It allows the hauler to monitor commercial customers to ensure adherence to contracts. It also keeps trucks legal on the street in the face of maximum weight limits.

Information can be wirelessly transferred to the office, enhancing the efficiency by providing real-time data for billing, recycling, or statistical purposes. A popular trend is the RFID tag, which records a time stamp when the bin is picked up. “One system even takes a time-stamped photo,” Nadeau notes. This adds accountability, alleviates customer complaint issues, provides theft protection, and has an economic benefit for haulers who routinely have to send smaller trucks just to pick up missed stops.

Beaver sees a definite trend toward more monitoring—everything from fuel consumption and temperatures and fluid pressures to location, weight, and stress and strain. “We’re getting more requests from haulers to record events, so you’re seeing scales and RFID, which enable route and load management.”

It also permits fleet managers to schedule preventive maintenance and avoid premature failure of components because of stress from overloading. Operating costs are multiples of the purchase price, Beaver states. Maintenance—or planned downtime—affects profitability. Proper monitoring can mean the difference between scheduled maintenance and unplanned repair.

Accountability for drivers comes in the Orwellian form of GPS. “The big joke used to be ‘did the guy take a nap?’” laughs Scott Kanne, vice president sales and marketing for Wayne Engineering, whose demonstration fleet of 20 trucks all come standard with GPS. With today’s GPSs, information collected in the truck is sent to the office in real time, including statistics on where the truck is, ongoing real-time management, driver and truck performance, and even maintenance reminders. Routing changes are easier to manage, whether an operator is picking up a route, driving a new route, or avoiding construction detours. “We need to know in today’s world,” Watje says. “We need a window into what’s going on.”

The problem is, figuring out what’s going on when something goes wrong has just become exceedingly complicated. “Truck chassis

were simple, but to diagnose a problem these days, maintenance shops have to have a laptop,” confirms Kanne. With advanced electronics and hydraulics, it’s helpful to have management systems “talk” to each other. Maintenance is much more involved, Watje adds. Controls are sophisticated, and mechanics must adapt to onboard electronics and telematics.

Neale can count five basic control packages onboard, including a company-controlled engine, transmission, brakes, and electrical chassis components, and says haulers are adding systems, such as scales, cameras, RFID, and tire-pressure monitors. “A lot of information is used for the operation of the vehicle. You need a way for the systems to interface. You need to dovetail all the systems.”

Because outward visibility is critical, Neale says there’s a push at Autocar to integrate seamlessly. “We must provide all the features

the customer wants, but we can’t hinder vision.” Wayne showcased a control system on a front loader at Waste Expo that featured a new touch pad integrated on the dash. The simple icon with international styling was easy to see and understand and gives the cab a cleaner look. It also means “the mechanic sees a reduction of 800 feet of wire,” Watje estimates, resulting in less corrosion and ease of maintenance.

Maybe mechanics should be grateful for technology. However, as the technology becomes more complex, mechanics need additional training. As the level of technological sophistication grows, the demand to maximize efficiency increases. Customers are demanding, Beaver says. “Their expectation

is that over the seven-year life of a truck, it should operate at peak performance.” That puts pressure on fleet managers and mechanics.

According to Neale, a government mandate for onboard diagnostics is coming in 2016, which he believes will push manufacturers to upgrade their systems and look at other features, tying them all together. It gives manufacturers an opportunity to incorporate at the time of build so it’s simpler than addon systems.

Retrofitting is costly, so Watje believes there should be open architecture to build in features for future needs and compatibility. “Manufacturers should anticipate future needs and wants. These things will start happening, because customers like technology.”

The industry’s willingness to embrace new technology is affected by the economy, Beaver believes. “When the economy goes down, everything goes down. People can’t afford the upfront cost of investing in new technology. But when the economy goes up, the old equipment doesn’t come up with it.” That’s why he expects to see the long-term shift to automatic side loaders accelerate and says more fleets will adopt dynamic route optimization software that can make adjustments to routes in real time based on conditions.

“If they’re not asking for [features] in six months, they still may need it in two years,” Kanne forecasts.Automation has enhanced productivity, safety and ergonomics in the collection vehicle industry. The Slammin’ Eagle by Curotto Can elevates those advantages to a new level. “All [existing] technology has an arm behind the cab,” says John Curotto. “Our product is unique.”The Slammin’ Eagle is a proprietary design featuring an arm with grippers that pick up garbage cans and empty them into a container in front of the cab, which then empties into the truck as it becomes full. It addresses some industry issues, such as ergonomics. “If drivers are looking in their mirrors,” Curotto explains, “there are safety, shoulder, neck, and back issues.” This configuration keeps the driver looking forward so he’s aware of what’s around him—and of what’s going into the dump cart.Contamination is an issue with side loaders, Curotto believes, but he claims that large fleets using his system have achieved as little as 4% contamination. Because of the lower curbside loading height, the operators can see the material and reach in to remove prohibited items, eliminating hazardous material and contamination in recycling. “They’re able to mitigate at the source.”

Doing so increased productivity. Other features also promote increased productivity. At a time when rolloff and commercial revenue is down, many haulers are relying on residential accounts, so they’re taking a hard look at productivity. The ability to take everything at the curb speeds collection and keeps the driver safely in the cab. The Split Eagle version eliminates the need for a second vehicle to follow to pick up bulky items or greenwaste.

Downtime is reduced because the arm is easily interchangeable. Curotto estimates that 65% to 75% of downtime on an automated truck is related to the arm, but the Slammin’ Eagle arm can be disconnected and replaced in just minutes, putting the truck back on the road. The initial capital cost is higher than that of other styles, but Curotto insists that significant productivity gains translate into needing fewer vehicles. And, because they work with all body manufacturers and can be retrofitted in the field, adding this automated feature doesn’t require the purchase of a new truck.