Resource Management: The Water Audit Process and Its Value to Utilities

Executive Summary

Every year, utilities are losing millions of gallons of water—and significant revenue—for a variety of reasons, including aging infrastructure and outdated measurement practices. With new mandates for tighter water management and accountability being established by the US Department of Energy (DOE), utilities are under greater pressure to more efficiently manage their resources. Today, automatic meter reading (AMR) and Advanced Metering Infrastructure (AMI) technologies represent an opportunity for water utilities to make significant improvements in data collection and measurement accuracy. These systems are just part of the total solution to mitigate water loss. A water audit, based on guidelines codeveloped by the International Water Association (IWA) and American Water Works Association (AWWA), evaluates a utility’s water management and data monitoring processes and establishes a road map for best management practices and continuous improvement.

Introduction

Municipalities and water utilities are being asked to do more with less. With fewer resources available, utilities are taking a closer look at their data collection and management practices—and exploring new efficiency methods.

The federal government is forcing utilities to further evaluate their practices and conserve water as well. Executive Order 13423 (US DOE 2007), signed into law January 24, 2007, requires federal agencies to reduce water consumption intensity (gallons per square-foot) 2% annually, starting in 2008 (through 2015)—for a total reduction of 16% versus 2007 numbers. The executive order also directs federal facilities to conduct water audits on 10% of its infrastructure every 10 years. These mandates to conserve water will remain in place and are likely to become more stringent in the years ahead.

A water audit is a cost-effective way for utilities to fully examine all facets of distribution, operation, and performance. Using sound accounting principles, a scientific framework, and established baselines, a water audit categorizes all water within a utility’s system, identifies water lost, pinpoints system deficiencies, and facilitates the implementation of corrective actions to improve overall performance. A water audit also helps utilities prioritize those recommendations into immediate and long-term solutions, providing direction for budgetary planning in the months and years ahead.

The three main components of the water audit process are discovery, intervention, and evaluation (USEPA WaterSense—an EPA Partnership Program). The discovery process is a fact-finding assessment, which examines how the utility operates and establishes performance baselines for testing. Conclusions drawn throughout this process result in recommendations for intervention or corrective action. Evaluation of the corrective actions—and resulting adjustments and process improvements—take place on an ongoing basis.

If correctly implemented, the water audit changes the way a utility views itself and empowers employees to look for ways to operate more efficiently and improve performance. Simply put, ongoing evaluation becomes part of the utility’s culture—and helps create an environment focused on continuous improvement and guided by best management practices.

The Value of a Water Audit

There’s little doubt that the nation’s more than 880,000 miles of drinking-water infrastructure is old and outdated. According to the American Society of Civil Engineers 2005 Report Card for America’s Infrastructure, nearly $1 trillion in critical drinking and wastewater investments are needed in the next two decades to meet the country’s water needs, and to repair and replace aging infrastructure and facilities (American Society of Civil Engineers 2005). Utilities need to supply safe, fresh drinking water and do so at a reasonable cost. However, leaks and poor data management practices are costing utilities millions of dollars annually in lost revenue. In addition, utilities are facing soaring energy costs, which can also be reduced through improved water management.

To gain a better handle on their water management, more utilities today are considering a water audit. A water audit examines the flow of water from the incoming source of treatment through its facility and distribution to the end user.

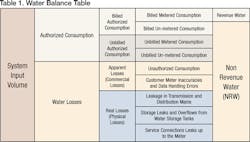

A water audit is based on a simple premise: All water can be accounted for via metering or estimation, in either beneficial consumption or wasteful loss. No water is truly “unaccounted for.” This previously used industrywide term has been replaced with new terminology that more accurately describes water losses within a utility as “Apparent Losses” and “Real Losses.” The IWA/AWWA has developed a water balance table to schematically illustrate the various components of accounted water (American Water Works Association). As data is collected throughout the water audit process, it can be categorized and attributed to at least one area of the water balance table—and thereby provide utilities with a view of their total water usage from a billing and management standpoint.

All system water falls into two broad categories: authorized consumption (intended uses) and water losses (inefficiencies). While the two segments of authorized consumption—billed and unbilled—are simply understood, the water loss categories—apparent and real—are more difficult to grasp.

According to the IWA/AWWA, apparent loss occurs when water that should be registered and billed to a customer is “lost” due to theft, meter inaccuracy or billing errors. In other words, apparent losses originate from the meter. By minimizing apparent loss, a utility will start recouping lost revenue. Real loss, on the other hand, involves the physical loss of water from a distribution system prior to ever reaching the customer. Actions to reduce real loss will lower a utility’s operating cost through savings found in less production and electrical use. In fact, a utility can save as much as 30% by simply producing less water (USEPA, WaterSense—an EPA Partnership Program).

A successful water audit will identify areas of apparent and real water loss, recommend solutions to address those areas, and help a utility become more efficient by following best management practices. The AWWA outlines how utilities can implement the water audit, mitigate loss, and operate more efficiently in its M36 Water Audits and Loss Control Programs manual. Many utilities choose to engage consultants to manage the audit and help execute process improvements.

The Discovery Process

The first step in a water audit could be described as the discovery process. During this phase, the audit team gains an initial perspective into the utility’s operations—a perspective that leads to recommended corrective actions and improved efficiency. Common steps in the discovery phase include (AWWA, WaterWiser):

- Production review

- Collect information from all relevant systems and facilities (e.g., review records, pumping stations, flow in and out of reservoirs and tanks; identify piping problems of systems not currently metered; review input/output of water used in the treatment process)

- Distribution system confirmation

- Review existing records, reports, plans, meter routes, maps, and distribution system; interview personnel; conduct field investigations

- Establish flow rates based on estimates or metering of water into and out of the distribution system

- Test and calibrate source meters at plants and pumping stations; determine best correction factors to adjust pump figures; quantify non-metered usages such as non-metered connections, line flushing, construction usages, firefighting, etc.

- Large/small meter consumption sizing and application analysis

- Detailed analysis of large meters; survey of the large meter population and training of work force to identify issues that tend to compromise metering performance; analysis of small meter program to determine age, functionality and accuracy

- Establish benchmarks

- Evaluate where water loss is occurring

- Study gaps in data

- Evaluate solutions

- Select best interventions

Throughout the process, consultants team with utility management, technicians, and other stakeholders to identify goals and objectives. Once the audit is underway, consultants involved in the process will likely conduct periodic onsite visits, based on the size and scope of the project. Keep in mind, “discovery” and system monitoring is ongoing throughout the audit period itself and beyond. In fact, to eliminate the potential for interpretation errors generated by perturbations in seasonal measurements, an extended monitoring period is recommended. During this time, the team will likely continue to discover areas for improvement. Data analysis and recommended intervention can occur at anytime.

The Intervention Process

The intervention process involves selecting corrective actions and recommendations that satisfy immediate needs and provide the best return on investment (ROI) (USEPA 2009). While corrective actions are commonly applied after the audit has established areas of water loss in need of attention, intervention can also be applied early in the process to inefficient procedures identified by the audit team. Remember, the water audit continually evolves over the course of the process. Corrective actions applied early in the water audit to one area will likely impact other functions within the utility. That’s why corrective actions are constantly measured and reevaluated for their overall favorable impact on the utility.

Certainly, more than one corrective action may be implemented at the same time. Factors to consider when selecting corrective actions include: practicality, level of urgency, budget constraints, public benefit, and the ROI of capital improvements. The IWA/AWWA describes the steps in the intervention process as:

- Gathering further information

- Metering assessment, testing, or a metering replacement program

- Detecting and locating leaks

- Recommending corrective actions and implementation

- Repairing or replacing pipe

- Operation and maintenance programs and changes

- Administrative processes or policy changes

- No further action is required

The Evaluation Process

The evaluation process examines the corrective actions implemented during the discovery phase and intervention process and determines how successful they were toward achieving a utility’s goals (USEPA, WaterSense—an EPA Partnership Program). Benchmarks established in the water audit, and the corrective actions employed, should evidence significant strides toward meeting performance goals. Even in the evaluation process, adjustments and new corrective actions will likely be made to continually steer a utility toward continuous improvement.

Throughout the water audit, utility personnel will grow professionally and strengthen their capacity to operate more efficiently, resulting in a workforce more focused on best management practices. The IWA/AWWA describes the evaluation process as:

- Were the goals of the intervention met? If not, why?

- Do we need more information?

- How often should we repeat the audit, intervention, and evaluation process?

- Is there another performance indicator we should consider?

- How did we compare to the last audit, intervention, or evaluation process?

- How can we improve performance?

Mitigating Water Loss: Applying Pareto’s Principle

The key to a successful water audit is to find those areas where water loss is occurring—and mitigate that loss. A truly effective water audit also applies Pareto’s Principle, commonly referred to as the “80-20 rule,” to both real and apparent water loss. Simply put, this rule means that a “vital few” parts can have a disproportionate impact on the whole. In mitigating water loss, the “80-20 rule” can be applied to a number of scenarios including: 1) 20% of a utility’s leaks generally account for 80% of its water loss; and 2) 20% of a utility’s large meters account for about 80% of its revenue. Whenever appropriate, the water audit will apply the “80-20 rule” to prioritize corrective actions—and yield a strong return on investment (ROI).

Federal and State Standards

While Executive Order 13423 is the first mandate of its kind that directs utilities to perform regularly scheduled water audits on at least 10% of its infrastructure, there are no national directives requiring utilities to report annual water loss (USEPA, WaterSense—an EPA Partnership Program). Still, many states have established benchmark standards in water auditing to which utilities in their jurisdiction must comply.

A 2002 survey of states and their water loss practices is the last known and most recent effort undertaken to compare water loss policy by state (USEPA, WaterSense—an EPA Partnership Program). Table 2 is a summary of the 2002 survey regarding water loss, testing and auditing.

Some states have enacted more stringent water auditing standards for utilities in an effort to conserve water. In 2003, Texas passed a bill requiring utilities to file a standardized water audit once every five years. The Texas Water Development Board outlined specific water audit methodology for all utilities to follow that measures efficiency and water accountability, quantifies water losses, and ensures common water loss reporting across the state (Texas Water Department Board 2008). Similarly, New Mexico passed legislation in 2005 to “develop criteria for water system planning, performance, and conservation” for utilities. A year later, the state developed guides for utilities, including Water Use Auditing, Financial Planning and Rate Setting Guidebook, and Asset Management—A Guide for Water and Wastewater Systems. The New Mexico legislation is designed to help utilities become more proactive in meeting any new federal standards on water conservation, anticipate infrastructure repairs, and meet the challenges of a growing population (New Mexico Rural Water Association 2007).

Conclusion

All utilities lose a certain amount of water, but no water is truly “unaccounted-for.” It is possible through proper measurement and data analysis to determine real and apparent water losses. The key is to mitigate water loss as much as practical. A comprehensive water audit is the first step many utilities can take toward becoming better stewards of a precious natural resource, water.

With new aggressive federal mandates now in place to annually reduce water loss, the onus is on water utilities to ensure they are compliant. A water audit serves as a cost-effective way to identify areas in need of attention, outline solutions, and provide scientific justification that the remedial solutions brought forward generate the best ROI. A water audit truly is a road map for utilities to continually optimize their operations—and implement best management practices.

Improvement doesn’t end with the water audit…it really is a first step in achieving higher levels of efficiency.

References

American Society of Civil Engineers (ASCE), Report Card for America’s Infrastructure, 2005 Policy Recommendations for Drinking Water.

American Water Works Association (AWWA), WaterWiser, Water Audits and Loss Control.

Mathis, Mark, George Kunkel, and Andrew Chastain Howley. Texas Water Department Board Report 367, Water Loss Audit Manual for Texas Utilities, March 2008.

New Mexico Rural Water Association (NMRWA). Water Use Auditing: A Guide to Accurately Measure Water Use and Water Loss, 2007.

US Department of Energy (DOE), Federal Energy Management Program, Laws & Regulations, Executive Order No. 13423, Strengthening Federal Environmental, Energy and Transportation Management, January 2007.

US Environmental Protection Agency (EPA), Control and Mitigation of Drinking Water Losses in Distribution Systems, November 2009.

US Environmental Protection Agency (EPA), Office of Wastewater Management, WaterSense, an EPA Partnership Program.