The idea of organized collection and disposal of municipal solid waste (MSW) is relatively new, beginning in the mid-19th century. Bacteriological and epidemiological studies revealed that refuse dumped in city streets was the primary source of the plagues and epidemics that swept countries and continents. This finding resulted in the development of municipal refuse disposal schemes and operational practices that resulted in almost all municipalities disposing of their own MSW at disposal sites within their borders. In the densely populated portions of the country, this was accomplished with a combination of incinerators and landfills for the ash and open burning dumps for the waste in excess of the incineration capacity and for the items that would not fit in the incinerators. In the more rural areas, it was accomplished with backyard combustion in so called burn barrels and open burning dumps.

In 1930, the American Society of Civil Engineers published its first manual of practice for “sanitary landfilling” (unlined landfills where the solid waste was placed and compacted with bulldozers and soil cover was applied at the end of the day to prevent rodents), and there were two types, the “cut and cover” where a trench was excavated prior to placing the waste, and “at grade” where no excavation was required. During the Second World War, the US army used this method at training camps. The “sanitary landfill” was viewed as an environmentally sound means for the disposal of MSW. In 1944, the US Public Health Service was created, and although it dealt with solid waste disposal, there were no federal standards to enforce, so it tried to encourage the use of the sanitary landfill, and some of the larger municipalities did adopt the method. In 1968, only 6% of municipal land disposal operations surveyed by the US Public Health Service were considered adequate.

The incinerators were batch fed (a feed chute was opened, MSW was loaded into the furnace on top of the mass that was already on fire, the chute was closed, and the mass was allowed to ignite and combust until the fire was low enough to add more MSW), and the only air-pollution control was that the hot gases passed into a large “settling chamber” at a low velocity so that the large particles would settle to the bottom of the chamber and the gases would then rise up a stack to be discharged to the atmosphere. There were not only municipal incinerators, but also many industries incinerated their wastes, and many high-rise residential apartment buildings had their own incinerators. The only regulatory scheme for incinerators was the Ringelmann Smoke Chart. The Ringelmann Smoke Chart, giving shades of gray by which the density of columns of smoke rising from stacks may be compared, was developed by agricultural engineer Max Ringelmann. The chart was introduced into the US in 1897. It was adopted by the ASME for power-plant testing and by 1910 was widely used by compliance officers in jurisdictions that had adopted standards based upon the chart. The Ringelmann system consists of graduated shades of gray in five equal steps between white and black, reproduced by means of a rectangular grill of black lines of definite width and spacing on a white background: Step 0-All white; Step 1 [20%]-Black lines 1-mm thick, 10 mm apart, leaving white spaces 9-mm square; Step 2 [40%]-Lines 2.3-mm thick, spaces 7.7-mm square; Step 3 [60%]-Lines 3.7-mm thick, spaces 6.3-mm square; Step 4 [80%]-Lines 5.5-mm thick, spaces 4.5-mm square; Step 5 [100%]-All black. The jurisdiction would adopt one of the five steps as being in compliance. The compliance officer would stand on the ground and the hold the chart up and look at the emissions from the stack and compare the opacity of the smoke to the five steps. If the smoke was equal to or lighter than the standard that had been adopted, the facility was in compliance; if the smoke was darker than the standard that had been adopted, the facility was not in compliance.

The modern environmental movement could be said to have started with Rachel Carson’s book, The Silent Spring, published in 1962-or at least the book gave the movement significant momentum. The movement was mainly focused on things that were visible, such as birds and animals dying because of the use of chemicals; raw sewage discharges into lakes, streams, and rivers; and black smoke emanating from factories, power plants, and incinerators. The first Earth Day was held in April 1970, and that same year the EPA was created and congress passed the Clean Air Act (CAA), which contained the first US ambient air-quality standards and stack emission limits.

Although it took a number of years, the CAA caused most of the existing incinerators to shut down, since in most cases the cost of upgrading to meet the new CAA emission limits was five to 10 times the original capital cost of the incinerator. This caused local landfills to fill up at a much faster rate. Additionally, swamplands had been reclassified as wetlands, so the practice of locating new landfills in “worthless swampland” stopped, and it therefore became much harder to find locations for new landfills in the more densely populated areas of the country. In 1972, the EPA initiated “Mission 5000,” which had a goal of closing the estimated 5,000 open burning dumps across the country and replacing them with “sanitary landfills.” In 1976, the EPA concluded that “ninety percent of municipal and industrial solid wastes are disposed of on land in environmentally questionable ways, the results of which are potential public health problems through groundwater contamination by leachate, surface water pollution by runoff, air pollution from open burning, fires and explosions at dumps, and risks to ecological systems.” In response to this and other EPA reports, and lobbying by the environmental movement, the Resource Conservation and Recovery Act (RCRA) was passed in 1976, containing the first federal regulations for landfills.

Love Canal, NY, where homes and schools had been built on top of a hazardous waste landfill, became a household name in 1978, and in 1979 EPA initiated an emergency cleanup in the “Valley of the Drums” in Kentucky, where tens of thousands of drums of waste had been emptied into pits over the years and approximately 6,000 drums of various chemicals stood in the open, rusting and leaking, as shown on TV and in the newspapers. Both of these events motivated congress to pass the Comprehensive Environmental Response, Compensation and Liability Act (CERCLA, also known as “Superfund”) in December 1980. In 1982, the first National Priorities List was published by the EPA, and a number of municipally owned MSW landfills were classified as Superfund sites, as well as some private landfills that accepted MSW.

Table 1 presents a summary of a 1982 state-by-state landfill survey conducted and published in March 1983 by Waste Age magazine. Although there are clearly discrepancies in the data, and it is not complete, the table gives a rough picture of the state of the country’s solid waste disposal facilities in 1982, and it’s not good. In December 1983, Waste Age published a survey of landfill tipping fees at 77 landfills in cities across the country, with the average price being $10.80 per ton. That same survey contained the tipping fees for the 17 operating waste-to-energy (WTE) facilities, with the average price being $14.96 per ton for the 14 WTE facilities that were not tax supported.

The 1986 RCRA was amended to increase the standards for MSW landfills, and CERCLA was reauthorized and strengthened. All these federal laws caused the states to adopt similar laws, rules, and regulations.

The 1970s and 1980s

With the above as a setting, in the 1970s states and municipalities realized that the rules for solid waste management had changed significantly. Many states passed laws requiring counties and cities to develop compressive solid waste management plans. In the states where counties are strong units of government, one of the planning principals was that, as in the past, solid waste disposal had to be accomplished within the borders of the county. Where county government was relatively weak, such as in Connecticut and Massachusetts, a state agency was formed to plan and implement regional facilities. New Jersey encouraged a regional approach to planning and implementation. Florida required all counties above a certain population to consider WTE. Due to their size, Rhode Island and Delaware both formed state agencies to plan and implement facilities. Many states gave planning grants to the counties and cities to develop their solid waste management plans.

While many people claim that actual landfill crises and skyrocketing energy prices were the drivers for the large number of WTE facilities that were constructed in the 1980s and early 1990s, the author’s experience says that the actual drivers were four major solid waste management planning principals that were also perceived by most people across the county as being true:

- Since the rules had changed, there was a solid waste disposal problem that needed to be solved (although there was no real crisis).

- The problem was generated within a political jurisdiction, and it was the responsibility of the political jurisdiction to provide a solution within its borders, or join a regional solution.

- There were limits to the amount of MSW that could be recycled, so other methods had to be developed to deal with the waste remaining after recycling.

- Landfilling should be minimized, since locations for landfills were getting harder to find and many communities’ existing unlined landfills were polluting the groundwater (some were declared Superfund sites).

Additionally, in the 1970s, both the EPA and the DOE provided grants to municipalities and companies to develop facilities that would recover the energy and materials contained in MSW. While these grants were for gasification and Refuse-Derived Fuel (RDF) facilities that eventually failed, they helped stimulate interest in mass-burn WTE facilities.

The successful mass-burn WTE facility in Saugus, MA, developed by Wheelabrator, which became operational in 1975, the successful mass-burn WTE facility developed by Pinellas County, FL, that became operational in 1983, and the plentiful number of mass-burn facilities in Europe convinced many people, including municipal officials, staffs, consulting engineers, financial advisors, and investment bankers who visited those European facilities, that there was a proven, reliable, environmentally sound technology for recovering the energy contained in MSW-and that it could meet stringent air-emission standards and be a good neighbor. Those facilities overcame the bad impression that mass burn had obtained because of the closure of the US incinerators and the further bad impression that WTE had obtained due to the failures of the gasification and RDF facilities in the US.

In 1979, EPA awarded and administered grants to 62 municipalities across the country to plan and implement WTE facilities. (See the fifth listed item in the last section of this article for additional details).

In the 1980s, many WTE project proponents moved away from the yardstick of measuring cost of service in terms of dollars per ton of MSW and instead focused on the cost of service in terms of dollars per household per month for both solid waste collection and disposal. In this way, they were able to demonstrate that solid waste collection and disposal was a very inexpensive essential service, and if for a modest cost increase (since most of the cost was in collection and transportation, a relatively large increase in disposal cost resulted in only a modest increase in the total per household charge), the community could achieve an environmentally sound, long-term solution to its solid waste disposal needs, it was perceived by the general public as being worth the price. Even today, most people pay more per month for services such as water and sewer, Internet, cable television, or cellular phone service than they do for solid waste collection and disposal, and they pay approximately five to 10 times more for household energy than for solid waste.

Positive Political Drivers

The combination of these perceptions gave rise to the local project champion (or champions) who not only saw WTE as the long-term solution but, because of being a respected member of the community, was able to convince other leaders within the local power structure and the majority of the people within the local jurisdiction that WTE was the right thing to do, even though it was a higher cost solution in the near-term. Development of this political will was critical to overcome the project opposition.

Almost every existing WTE facility that the author is aware of had at least one local project champion. Project champions were usually relatively high placed in the local government. They were long-time community members and well respected by the power structure and others in the community. Typical project champions included solid waste directors, department of public works directors, county administrators, authority board members, or local elected officials. Some projects had more than one, but all had at least one.

The local project champion (or champions) was able to produce and sustain the political will that fostered most of the existing WTE facilities developed by counties and cities, such as those in Florida, Virginia, Maryland, New York, Pennsylvania, Michigan, California, and Washington. New Jersey had the same drivers, and political will, but developed a more regional approach for its WTE facilities, although there were still local project champions that drove the projects. The WTE projects in Connecticut and Massachusetts were mainly developed by state agencies or a consortium of local governments in a regional approach. All of these facilities relied on the perception (that was translated into how these facilities were planned for and implemented) that the problem needed to be solved by the local government jurisdiction(s). With the exception of a handful of merchant facilities, all of the WTE facilities that were developed involved a political jurisdiction (county or city) or a grouping of political jurisdictions (mostly cities or towns, and some counties).

Because the planning and implementation (gestation) period for a WTE facility averaged from five to seven years (some as short as three years, others longer at 10 to 15 years), which meant that at least one if not more election cycles occurred. The local project champion had to endure political setbacks caused by elections and needed to persevere, even if the political tide turned against the project.

Today’s solid waste professionals should understand that none of the existing WTE facilities came easy; most of them came very close to cratering at least once, if not more. Some did crater and were resurrected, sometimes more than once. Some of the existing facilities took 15 years from the start of planning before groundbreaking occurred.

In addition, many proposed projects never got off the ground due to a lack of political will or elections changing the political will from being in favor of building a WTE facility to canceling the proposed project. Some of the larger WTE projects that were proposed and then canceled by local governments due to changes in political will (some after both a location and a design/build/operate, or DBO, contractor had been selected) included, to name a few, Boston, MA; Rhode Island; New York City, NY; Philadelphia, PA; Oakland County, MI; Los Angeles and San Francisco, CA; and King County, WA.

Positive for Recycling, Negative for WTE

It is the author’s opinion that the major reasons why new WTE facilities are not being built in the US involve the exact opposite perceptions to those that existed in the 1970s through the late 1980s: There is no perceived solid waste problem by the general public, and solid waste generation is perceived not to be a local problem; therefore, solid waste disposal does not have to be performed locally.

Since the early 1990s, most people believe that their existing solid waste system works, and that it is reliable, relatively inexpensive, and pollution free. Therefore, whenever a WTE facility is proposed, it is perceived as a solution to a problem that does not exist, and facts are less important than perceptions.

As previously stated, one of the widespread perceptions that existed in the 1970s and 1980s was that solid waste was generated within a local political jurisdiction and it was the responsibility of the local political jurisdiction to provide a solution. People no longer perceive that to be true. The author does not have a definitive explanation as to why this has changed, but it definitely has.

However, the author believes that one possible explanation can be found in the words of Pogo: “We have met the enemy and he is us.” Starting in the late 1970s, solid waste professionals, planners and regulatory agencies, adopted and proselytized “Reduce, Reuse, and Recycle” (the “3Rs”) as the solution for solid waste issues. Those three words were promulgated to the general public as the total solution to solid waste issues. We are now reaping what we have sown. The general public now believes that by better applying those three Rs, we can solve the solid waste problem and eliminate the need for WTE facilities and landfills. Sometimes this is called “zero waste,” but with or without that label it now appears to form the basis for opposing any new WTE facility, lobbying to shut down existing WTE facilities, and also opposing new landfills or expanding existing ones.

While air pollution is the most often-cited concern relative to WTE facilities, and groundwater pollution is the major concern voiced for landfills, the basis of the argument is the perception that both are unnecessary if we apply the 3Rs to the maximum extent possible.

Table 2 presents a summary juxtaposition of the older versus the newer perceptions related to solid waste management.

A Changed Perception of Recycling and WTE

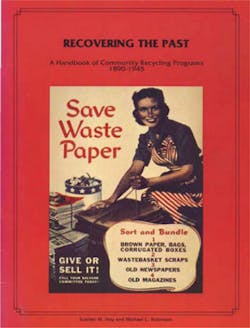

Although recycling is not new, in the past everyone recognized its limitations. The APWA publication, Recovering the Past, gave an excellent history of recycling starting in the 1890s through 1945. The publication also includes New York City Sanitation Commissioner George E. Waring’s large-scale recycling initiatives starting in 1895. In 1905, Waring built the country’s first WTE facility that generated electricity. It was a large incinerator with waste heat recovery and electric generation capacity in New York City. The steam generated by the combustion process was used to drive a conveyor belt onto which the solid waste was deposited and recyclable materials were removed at picking stations prior to the remaining waste being combusted. At night the steam also turned an electric generator that powered the lighting on the Williamsburg Bridge.

From the very beginning of WTE in the US, people had believed that recycling and WTE were compatible. Due to material shortages during World War I, the Waste Reclamation Service was created in 1917, whose motto was “Don’t Waste Waste.” The Waste Reclamation Service’s campaign was part of a national conservation movement dating back to the 1890s, advocating regulations for development, including the nation’s water, timber, land, and minerals. Many communities had recycling programs through World War I and the Great Depression, but then the need faded and prices fell, and many programs were abandoned. The next grass-roots recycling effort was during World War II, but during the 1950s and 1960s a “throwaway” society grew in popularity as the convenience of such things as non-returnable bottles, TV dinners on disposable plates, and plastic packaging became prevalent.

Recycling started to make a comeback with Earth Day in April 1970 and grew through the 1980s, although it was still recognized that there were limits to how much waste could be recycled. However, around 1990, the concept of recycling changed, and, unlike past efforts, today’s recycling advocates believe there are no limits to the types and amounts of waste that can be recycled, which makes WTE and landfills not only unnecessary, but also incompatible with recycling. Some of the perceptions about recycling and WTE have been fostered and reinforced by the solid waste industry, some by people who are devout recycling believers and/or devout anti-combustion believers. Table 3 presents a summary juxtaposition of the perceptions of recycling versus the perception of WTE.

From 1990, the perceptions and conventional wisdom produce positive political drivers for recycling and negative ones for WTE.

All the current political drivers line up for recycling and against WTE. Table 4 presents a summary juxtaposition of the political drivers for recycling versus the political drivers against WTE.

From 1990, the negative WTE political drivers result in lack of local project champions and lack of political will.

Due to the current negative drivers of WTE, potential project champions are smart enough to understand that even if they believe it’s the right thing to do, it would be committing political suicide and they would lose their credibility in the community if they were to take up the WTE banner, so they stay silent.

Some of the people with project-champion attributes have become project champions for nonconventional WTE conversion technologies because of vendor’s claims that the technology has overcome all the negative attributes of conventional WTE technology, making such technologies appear more palatable than mass-burn WTE. “There is no pollution.” “It produces a clean gas.” “There is no stack.” In some cases this has led to a perception that unconventional WTE conversion technologies are not controversial. However, in other cases it has led to opposition based upon the perception that it’s still combustion of solid waste, no matter what label proponents use.

Since the early 1990s through the mid 2000s, when no request for proposals (RFP) were being issued for new mass-burn WTE facilities, the WTE industry, including the author, has been trying to convince itself that the hiatus is only temporary and that a large resurgence of new WTE facilities is just around the corner.

The only new WTE capacity that has been added in the US since 1995 is that of the completed expansions of the existing WTE facilities in Lee County, FL, Hillsborough County, FL, and Olmsted County, MN, plus an expansion in Honolulu, HI, that recently broke ground. Several other proposed expansions have been deferred or are floundering.

While a few RFPs have been issued for new WTE mass-burn facilities and a few private developers have proposed unsolicited new WTE mass-burn facilities, none of these facilities have actually broken ground, and they are facing public opposition. In the last eight years there have been a large number of RFPs and unsolicited proposals for unproven “conversion technologies,” but none of these projects have started construction either.

Given the current hiatus (that has now lasted nearly 20 years), the author no longer believes that there will be a significant renaissance of WTE facility construction, and has developed some fact checks to see whether or not such hiatus is more permanent than temporary. Table 5 presents a summary juxtaposition of WTE industry conventional wisdom versus the fact check.

The Garbage Crisis Myth

It appears that a significant number of current solid waste professionals believe that one of the main drivers for the development of the existing WTE facilities was a garbage crisis. The author’s observations during that time period hold that there never was a garbage crisis, except in the solid waste trade press, newspaper headlines, and TV news programs. The following paragraphs explain why there was never a real garbage crisis and why myths arose about garbage crises due to misuse of certain projections and the occurrence of certain events.

In the 1970s and 1980s, many states published projections on how many years of landfill capacity remained within their state, and many showed that they would run out of disposal capacity in five to 10 years (sometimes as short as three years). However, that assumed only the existing permitted disposal capacity and did not take into account expansions of existing landfills and development of new landfills. The solid waste industry trade press, general newspapers, and TV news occasionally used these projections to create such dramatic headlines as “Garbage Crisis”. It never occurred, however, since expansions were applied for and permitted and new landfills were located, permitted, and opened before the existing capacity was anywhere near being exhausted.

One of the most visible and most widely publicized symbols of the purported garbage crisis was the Mobro 4000, also known as the “Garbage Barge.” On March 22, 1987, the Mobro 4000 sailed from Islip, NY, for Morehead City, NC, with a cargo of 3,000 tons of MSW. However, the private interests who had arranged to ship the waste to a gas conversion project in North Carolina had neglected to obtain the necessary approvals. As a result, North Carolina refused to allow the barge even to moor. The Mobro 4000 continued on its way, traveling to the Gulf of Mexico in search of a friendly government willing to accept the MSW for disposal. What followed was a highly publicized series of refusals by Louisiana, Alabama, Mississippi, Florida, New Jersey, the Bahamas, Mexico, and Belize. On its return home in May 1987, New York City prohibited the barge from docking or unloading within its waters. Meanwhile, the private carter legally responsible for the waste declared bankruptcy. In July 1987, a plan was announced to take the waste to the Southwest Incinerator in Brooklyn, open up each bale to inspect for and remove any hazardous or infectious waste, incinerate the remaining waste, and bury the ash residue in Islip’s landfill. In September 1987, 400 tons of ash residue were buried in the Islip landfill. Pictures were on national television at least once a week. After five months, 6,000 miles, and eight refusals to allow unloading, the Garbage Barge became a household word.

Numerous organizations, including the solid waste industry trade press, used pictures of the Garbage Barge and the five-month ordeal to try to convey the perception that there was a solid waste disposal crisis.

At the time, the New York Department of Environmental Conservation (NYDEC) estimated that within seven years all of the landfills presently operating in the state of New York would be full or closed. The Garbage Barge’s story was said to serve as a reminder of the urgent need to reduce discards and find new ways to handle solid waste.

People in the WTE industry wrote articles and made presentations about how the Garbage Barge was the greatest shot in the arm for the industry and how it was going to drive a new wave of WTE facilities. However, no new WTE facilities were implemented due to the Garbage Barge; those that were constructed after the saga ended were well on their way to implementation prior to the barge leaving Islip.

Although there were lots of headlines and TV time devoted to the impending Garbage Crisis, it was only good for conversation and cocktail party talk. The people that watched on TV and read the articles and made presentations about the crisis all had one thing in common: The garbage they put out in the morning was gone when they came home at night, so they could all laugh about the Garbage Barge and worry about the Garbage Crisis, but it had no real affect on anyone’s lives.

For a glimpse of what a real garbage crisis looks like, we might do well to remember the 1976 strike by the private garbage collectors in New York City. The strike lasted less than a week before a settlement was reached, due to political pressure and threats to use the state’s National Guard to collect the garbage. Until people have to drive or walk past those types of mounds of garbage and until the garbage left at the curb in the morning is still there in the evening, there is no actual garbage crisis.

The Good, The Bad, The Ugly

In the 1970s and 1980s, not everything was rosy, and WTE facilities were not built in a day. Some were implemented quickly, most took a long time and suffered setbacks, and a large number were canceled or abandoned. The following are some examples that run the gamut:

- In 1974, the author of this paper authored the Westchester County, NY, Solid Waste Master Plan, which recommended a mass-burn WTE facility for the disposal of solid waste from the entire county. The county executive accepted WTE, but believed that mass-burn was obsolete technology and selected the Union Carbide (UC) pyrolysis (gasification) system instead. After a few years of negotiating with UC to no avail, the city of Peekskill in Westchester County volunteered to host a mass-burn facility at a site on the Hudson River about five miles north of the Croton Point landfill, into which most of the county’s unincinerated waste went for years, and about 10 miles north of the Indian Point nuclear power plant (both of which were also on the Hudson River). Institutional mechanisms were put in place, an RFP was issued in 1979, and Wheelabrator was selected to own, design, construct, and operate the WTE facility, which became operational in 1984, some 10 years after the initial planning work.

- In 1974, the Commonwealth of Massachusetts issued an RFP for a WTE facility to be constructed in northeastern Massachusetts. A WTE facility vendor was selected in late 1975. Site selection commenced in 1976, and the location was selected in 1977. Starting in 1977, the commonwealth negotiated waste supply agreements on behalf of the cities and towns with the selected vendor, and negotiations were concluded in 1979, when the process for each city and town to authorize signing the agreements began, concluding in 1981. Environmental permitting and host community negotiations took several more years and the WTE facility became operation in 1985, some 11 years after the RFP was issued.

- In 1977, the author of this paper assisted the former commissioner of sanitation for New York City (NYC) and the then current commissioner of sanitation for NYC in developing the solid waste master plan for NYC. The plan’s basic strategy was to have each borough dispose of its own waste (except for landfilling of the residuals) and set forth constructing some 11 WTE facilities and at locations specified in the plan with a total combustion capacity of 16,000 tpd. The strategy was to move one project at a time forward in each borough, so that no borough president or city council member felt he was being singled out as the “dumping ground.” However, instead of letting the Department of Sanitation continue with implementation of the plan, the office of Mayor Koch decided to take over and move only the Brooklyn Navy Yard project, issuing an RFP in 1981 and selecting Wheelabrator. However, that broke the political strategy, and all the politicians from Brooklyn opposed the project. Additionally, in the late 1960s, NYC had a 90% architectural and engineering (A&E) design for a 6,000-tpd waterwall WTE facility at the Brooklyn Navy Yard (producing steam for the Manhattan steam loop), which was defeated. Many of the community opponents still lived in the area and knew each other, so the combination of political and community opposition made it impossible to move the project forward. The project eventually died, and NYC has no WTE facilities to this day.

- In 1978, the President’s Urban Policy (PUP) program was established. One of PUP’s features was a series of grants to municipalities to find planning studies to determine if a WTE facility would be appropriate for their community. Grants ranging in size from $50,000 to $500,000 were made to applicants in 1980. The author of this paper authored the EPA Resource Recovery Management Model that was used by EPA to guide the grant recipients through the feasibility and implementation phases. Of the 62 grant recipients, approximately 14 WTE facilities were constructed across the country (about 22% of the total number of potential projects).

- The last large WTE facility to become operational was in August 1995 and is located in Montgomery County, MD. However, the roots of that WTE facility go back to 1979, when Montgomery County hired Mitre Corp. to perform a WTE feasibility study, a three-volume, 5-inch-thick report that was completed in 1980. One of the two alternatives that Mitre determined as feasible was essentially the current facilities, except Mitre projected using truck-haul rather than the now existing rail-haul to transport the MSW. The county decided to move forward with the implementation of a WTE facility, and in 1981 some 26 officials and consultants from Montgomery County and other jurisdictions and organizations participated in a 14-day tour of European WTE facilities. The project went through many configurations and lead agencies over a number of years. In 1985, the county administrator selected the present WIT facility site (which had been included in the 1980 Mitre report), except that he included rail transportation rather than truck transportation from the transfer station to the WTE facility. Opposition sprouted but was eventually overcome. Pursuant to an REP issued by the Northeast Maryland Solid Waste Authority, a service agreement was entered into in 1990. Groundbreaking took place in 1993, some 14 years after the initial decision to proceed was made, and during that time the county, various public agencies and their consultants worked diligently to bring the project to fruition, and the results of a number of local elections during that time period caused the project to change direction a number of times.

- One of the 1980 PUP grant recipients was a collaboration of Hillsborough County, FL, and the city of Tampa, FL (the county seat), who were pursuing a joint WTE facility. In 1981, Tampa decided to pursue its own WTE facility and dissolved the partnership. The consultant to the joint project was hired by the city to develop the project. The county hired CDM to investigate the feasibility of a county WTE facility. The author of this paper was the project manager for CDM during the planning and implementation of the county’s WTE facility. In early 1982 the county accepted the results of a feasibility report to implement its own WTE facility. In 1982 a countywide site selection was performed, and the location for the WTE facility was selected. In 1983 a tour of European WTE facilities was undertaken and zoning and land use for the selected site was changed to allow the construction of the WTE facility. Also in 1983 and early 1984, the state air-quality permit was obtained. In 1984, the RFP for a DBO contractor was prepared, a contractor was selected, contract negotiations were concluded and bonds were issued to finance the project. Groundbreaking occurred in January 1985, some three years after the county’s decision to implement the project was made.

- In 1974, the board of supervisors authorized Sunset Scavenger Co. (SSC) to provide a solution to San Francisco’s solid waste disposal needs that would reduce dependence on landfills, generate electricity, and increase recycling. In 1977 SSC proposed a 2,000-tpd RDF facility adjacent to its transfer station in Brisbane. In 1983, Brisbane voted down the facility by a three-to-one majority.

- In 1974, the Rhode Island Solid Waste Management Corp. (RISWMC) was formed by the state legislature. In 1978, RISWMC issued an RFP and received proposals for a 1,500-tpd WTE facility, selected a DBO contractor in 1979, and purchased the property for the WTE facility and the adjacent landfill in 1980. In 1984, the WTE facility location changed to Quonset Point Industrial Park, and $225 million in bonds were sold to construct the WTE facility. In 1985, the project was abandoned due to political and environmental issues.

Conclusions

It appears that since around 1990, the general public in the local governmental jurisdiction where a WTE facility is proposed to be built places a higher value on such things as “increasing reduce, reuse, and recycle,” “zero waste,” “the cheapest alternative possible,” “since it goes away, there is no problem to solve,” “reduce local air pollution,” or “maintain local aesthetics,” than on the things the WTE industry it trying to claim as major advantages, such as “green energy,” “renewable energy,” “fewer greenhouse gas emissions,” “reduces dependence on foreign oil,” “environmentally superior to landfills,” or “long-term solid waste disposal solution.” Therefore, proposals to build new WTE facilities are continually being rejected.

The author has no great words of wisdom on how to obtain a significant renaissance for the WTE industry. He wishes he did. All he can say is that, for the foreseeable future, it will take a lot of hard work, perseverance, and money to continue to try to move WTE projects forward, and when the earth, the moon, the stars, the public perceptions, and the politics align just right, there will be a groundbreaking for a new WTE facility in the US.

While you continue pursuing the implementation of new WTE facilities, please remember, that based upon the data available to the author, in the 1970s and 1980s the success rate was approximately 20%. This means that four out of five projects that were proposed were never built, so even in the good times it was a long, hard row to hoe.