Waste-to-energy is a multifaceted concept; it means different things to different people, is underestimated in complexity, and is questionable in terms of profitability and carbon neutrality. Waste can be solid or liquid. Gaseous waste products are referred to as emissions. Energy can be a stream of electrons injected into the grid as electricity, or it can take the form of such combustible commodities as ethanol or synthetic fuels. The emissions from converting solid waste into energy, and the restriction thereof, have a significant impact on the way energy is generated. This discussion will be restricted to “organic” solid wastes.

The conversion of organic solid waste into energy is not a new technology. “In 1885, the US Army built the nation’s first garbage incinerator on Governor’s Island in New York City harbor.” (See “A Brief History of Solid Waste Management During the Last 50 Years,” by H. Lanier Hickman.)

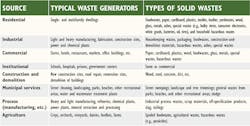

The solid-waste-to-energy industry starts with disposable goods from every sector in the economy. Each sector generates different kinds of waste each varying in composition (see Figure 1 and http://tinyurl.com/barry-stevens451).

The makeup of the waste is further influenced by lot, location, and time of year. The only norm in this business is that there is no norm.

Traditionally, energy was derived from waste by incineration. Heat generated from the combustion process was harvested and converted into electricity. The heat boils water that in turn powers steam generators to produce electric energy.

Today, organic wastes can be converted into fuel by two different strategies: thermal and non-thermal.

Thermal technologies include gasification, thermal depolymerization, pyrolysis, and plasma-arc gasification.

One technology that is pushing its way toward commercialization combines pyrolysis with the Fisher-Tropsch (FT) synthesis. The pyrolytic/FT pathway begins with the pretreatment (sorting, crushing, and drying) of the solid waste feedstock, which is then moved to a slow pyrolysis treatment at 900°C (the treatment involves a gasification process in the absence of oxygen) to generate syngas (CO and H2), which is subsequently cleaned and refined into liquid fuel by an FT process. This above description is a much-simplified version, excluding the complexity of the actual process and a number of the process steps, variables, and parameters. FT is a sophisticated catalytic technology patented by Franz Fischer and Hans Tropsch, working at the Kaiser Wilhelm Institute in Germany in the 1920s.

Non-thermal technologies or biological processes used to generate fuels include anaerobic digestion, fermentation production, and mechanical biological treatment. Like the pyrolytic/FT pathway, any generalized description may not be representative of other non-thermal conversion processes. The anaerobic digestion process utilizes microorganisms to break down biodegradable material in the absence of oxygen. It begins with a pretreatment to optimize the amount of digestible material and moisture content as well as to remove harmful contaminants from the organic feedstock, which is then “digested” by bacterial hydrolysis to produce insoluble organic polymers such as carbohydrates. The carbohydrates are then made available to acidogenic bacteria, which convert the sugars and amino acids into carbon dioxide, hydrogen, ammonia, and organic acids. The organic acids are subsequently converted by acetogenic bacteria into acetic acid, along with additional ammonia, hydrogen, and carbon dioxide. Finally, methanogens convert these products to methane (natural gas), carbon dioxide, and trace amounts of contaminant gases such as hydrogen sulfide. The methane can be burned to produce both heat and electricity or used as a fuel after “scrubbing” to remove the sulfides.

The one feature common to incineration, FT, and biologic conversion of waste-to energy is the use of solid waste as a feedstock. All wastes are not created equally and therefore cannot be uniformly applied to generate energy, be it electricity or fuel. This is the primary risk in the energy-from-waste industry. The type of energy generated depends on what actually constitutes the solid waste. Sorted material with all plastics, glass, and metal removed (and with no construction debris) poses fewer issues. If construction debris is included, there may be pressure-treated lumber present, which has the potential to create such aldehydes as formaldehyde in the flue gas. There will also be some heavy metals such as cadmium or chromium. Plastics can produce more monoxide but can also increase tar formation, any of which can inhibit the performance of or poison the FT catalyst. Also, the composition of the syngas is critical to the effectiveness and efficiency of the process. In the aforementioned biological process, the feedstock must contain mostly digestible or fermentable material. It must have the right moisture content, and it must be free of contaminants.

Outlining the right feedstock composition for each of these processes is far simpler than obtaining it. From the complex and unpredictable nature of solid waste and testing and sampling protocols to determining the syngas or biogas composition from each feedstock and tying that to determine the quality and cost of the product (electricity or fuel), it is far from certain what you get, even under controlled conditions. At the end of the day, the estimated capital cost to build, operate, and maintain a waste-to-energy processing plant is highly questionable.

Finally, the energy balance of a waste-to energy plant is of utmost importance for the production of energy from waste. The sample calculation given below is a gross, first-order approximation of the amount of energy consumed to produce a given amount of energy. The values used here were estimates based on a theoretical pyrolytic/FT plant that converts municipal solid waste into fuel-grade diesel. These values were averages obtained from field research. Parameters and assumptions are given in the notes below the calculations.

Significantly more sophisticated calculations can be found in a report by the Stevens Institute of Technology, BASF Catalyst, and the Golden BioMass Fuels Corp. on the investigation of energy balance, in broad outline, for the production of a high-quality synthetic diesel from residual crop biomass via a Fischer-Tropsch route (www.greencarcongress.com/2011/05/manganaro-20110516.html). Its calculations took the following into consideration:

- The harvesting of surplus biomass (such as crop residue)

- The local pyrolyzation of the biomass into pyrolysis oil, char, and uncondensable gas

- The transportation of the PO to a remote central processing facility

- The conversion of the PO at this facility by autothermal reformation into synthesis gas (CO and H2)

- The Fischer-Tropsch synthesis of the syngas into diesel fuel

The crude analysis shows that a hypothetical 50-tpd conversion plant producing fuel-grade diesel at a 20% overall yield from raw incoming feedstock generates over $1.1 million of gross revenue per year. A formal pro forma capturing all costs and other revenue can then determine the internal rate of return and bankability of such a project.

In closing, there is no question that converting waste-to-energy is a necessary sustainable and renewable enterprise, even if it serves no other purpose than to remove recyclables and to allow landfills to remain open due to lower volumes of waste. However, it is not a business to be taken lightly. Processes are new, advanced, and in many cases proprietary. Translating patents to operations is far from trivial. The chemistry, thermodynamics, and equipment design are complex. Operating systems may be beyond R&D and the pilot stage but questionable as a cost-effective commercial plant. Instant mavens, who see gold in that garbage, beware. Better to use the knowledge of those who have scar tissue to show in this business.