Green Infrastructure Sizing Criteria Development Part 2

“Everything should [still] be made as simple as possible but not simpler.” –Albert Einstein

Summary of Part 1

The purpose of this article in two parts is to describe the current or trending establishment of design sizing criteria for green infrastructure (GI) and to suggest some problems with current methods or trends and also, perhaps, an approach that can meet the objectives of a local government or facility but avoid some of the problems of past standards. The goal is to make it as simple as possible but not simpler…and not more complex than useful.

In Part 1 we described stormwater’s rather consistent history of developing simple design standards that later prove to be inadequate to protect the public or to do what they purported to do. We recognized EPA’s current abandonment of its attempts to establish a national GI standard in favor of encouraging state and local governments to forge ahead on their own with strong official encouragement but meager financial backing. Recently it has become clearer that EPA may use the event of reissuance of local and state permits to try to bring about the establishment of local criteria, various law suites notwithstanding. Thus, the ideas in these articles may be timelier than supposed.

We summarized the generic design criterion as expressed by EPA succinctly as:

For my local stormwater program the right daily rainfall volume (percent storm or rainfall depth) must be captured and retained on site through the use of green infrastructure.

We recognized within that statement five elements of commonplace GI criteria setting that each seem to have gone a bit awry: (1) the confusion of combined sewer overflow (CSO) and municipal separate storm sewer system (MS4) program objectives; (2) the problems with the use of daily rainfall analysis; (3) the use of a percent of daily storm capture criterion; (4) the alternate and equally problematic use of a depth-of-capture criterion; and (5) the tacit requirement within these criteria for instantaneous volume capture.

In summary:

- All GI structures are a combination of a bucket (instantaneous volume capture) and a hose (emptying of the bucket into the ground, air, or elsewhere).

- The need under CSO programs is for near instantaneous volume capture to reduce peak flow, while the desire under MS4 and related compliance programs is for capture and overflow combinations that mimic some predevelopment or “acceptable” hydrologic response to rainfall.

- GI as a peak flow reduction approach often appears to function as undersized detention. Thus it would require lots of sites, or very good “hoses,” to make GI work for peak flow reduction in the larger flood flows. But as a volume mimicry approach, GI can be very effective even for highly developed sites.

- EPA-based recommendations for the use of daily rainfall guidance are arbitrary and may often be inaccurate in establishing actual sizing design standards, but can sometimes “accidently” approximate the target established by more rigorous methods.

- The percent storm criterion (e.g., 95% storm capture) carries an illogical foundation in that it requires the exact same site to have to meet different capture requirements depending on where in the country it is located (e.g., the same site must capture 2.03 inches in Memphis but only 0.97 inch in Phoenix for the same percent storm, even though physics dictates the site would respond the same way no matter where it is located). When we do this we unwittingly force designers to often depart from the hydrologic mimicry mandate.

- In a similar way, the depth-of-capture criterion requires a site with slow-infiltrating soils to capture the same volume of rainfall as a site in the same locality located on sandy soils. Nature cannot accomplish this, and when we try, we may again unwittingly require designers to depart from the hydrologic mimicry mandate, or seek to develop the more sandy soils.

- The tacit depths or percentage capture requirements must be met regardless of the rainfall intensity. This, in practice, results in developers designing and sizing structures for the instantaneous capture of the design depths. This ability is unseen in nature except in karst or pond situations, and tends to relegate natural features such natural “small bucket” GI practices as trees to a secondary role.

We set aside the CSO compliance and maximized volume capture for this article realizing that the use of GI for that purpose is a specialized subset of the use of GI overall, and that often GI is used in those situations for a variety of reasons–volume capture efficiency being only one. Our focus is on the volume mimicry standard of the MS4 and related programs.

As a result the outcomes and outputs that may miss the mark by a little or a lot include:

- a wrongly placed emphasis on big volumes instead of natural processes;

- a wrongly placed emphasis on building on sites that infiltrate well instead of on sites that infiltrate poorly so hydrologic mimicry would be relatively easy to achieve;

- practices that are sized for instantaneous capture of the whole design volume leading to either expensive oversizing, or ineffective under sizing if the capture depth is small compared to reality;

- a need to mash up several design concepts to “credit” things such as trees or conservation areas, leading to spreadsheet complexity; and

- lack of emphasis on laying out sites for natural runoff absorption using natural processes in favor of construction of structural solutions.

Objectives of an Alternate Approach

If we were start with a clean slate and establish a set of objective evaluation criteria (OEC) limited to a new type of GI sizing approach, what might they be? Having participated in this discussion several times in both national and local venues, here is a “starter” consensus list of such OEC:

- Meets Compliance Requirements. Because a significant driver for all this is regulatory compliance, the approach must be acceptable to regulatory bodies and recognized to meet applicable compliance requirements.

- Mimics Predevelopment or “Acceptable” Hydrology. Because different non-impervious land use types respond very differently to rainfall, the approach must recognize, in a manner similar to nature, local differences in climate, soils, land uses, and other conditions pertinent to rainfall and runoff–not just impervious area–and it should balance mimicking storm response and annual overall hydrologic response within acceptable limits.

- Acknowledges Inter-Event Dry Periods. Because the time between storms is as important as the storms themselves, and the stream of rain data drives total hydrology, not just a design storm, the approach must reflect continuous local rainfall.

- Simple in Application. Because the majority of designers deal with stormwater only as a small part of their jobs, the method must be simple enough for casual use but internally consistent and accurate.

- Natural and Integrated. Because natural, nonstructural treatment is probably most reliable in the long term, the approach must create incentives to use natural vegetated (versus hard-surface constructed) methods as a first priority; and it must encourage such practices to be integrated into the site–not placed in some far forgotten corner.

- Cost Effective and Maintainable. Because it is relatively new and often voluntary, the approach must feature relatively reliable and low-maintenance designs whose lifecycle cost and return-on-investment characteristics are attractive.

- Hard to Circumvent. And finally, because some engineers are so deviously clever, it must anticipate “hacks” and adjust quickly to close any perceived vulnerabilities.

It goes (almost) without saying that to be ultimately successful, the development of an effective sizing criterion is but one small part of a comprehensive GI or volume-based stormwater program and, if developed by itself, will probably not keep a GI program from failure no matter how good it is. It must be combined with the comprehensive set of activities and tools (e.g., education, examples, ordinances, incentives, procedures, location, or design alternatives) that make up a GI successful program.

Framework for New Sizing Criteria

We’ll use Nashville, TN, as an example in the development of a framework for GI sizing because there has been significant work done there in the development.

However, a similar analysis can easily be done for any location. This is particularly true since the publication of EPA’s National Stormwater Calculator. It provides the power of SWMM-based continuous simulation modeling in a convenient and automated format. Although some of the output is provided in daily storm amounts (see part 1 of this article for some problems with that), the parameters of concern are offered on a total-data basis. In addition, data are automatically available with simple point-and-click actions, and pertinent GI structures and key soils and land-use data can be entered for quick “what if” analysis or development of design figures. It might even be possible to use the calculator as the design tool of choice for a local community, though more flexibility would be necessary. We tested its output with our own modeling to see if such criteria development could be accomplished with it and found it very similar after a couple tweaks in design approaches. SWMM was used in both cases, so the similarity is to be expected.

And perhaps now is the right time for the obligatory disclaimer that all models are only as good as the ability of the algorithms to mimic key natural processes, and uncalibrated models that do mimic natural processes are far better at predicting change in numbers than in estimating absolute numbers. Unless the site has some very particular features, the history of SWMM continuous simulation modeling’s accuracy is fairly well proven at this point and far superior to a theoretical event-based model.

The following sections describe different features of approach framework development.

Sizing Standard. The first step in framework development is to establish an attainable goal that, to the maximum extent practicable, reflects the hydrologic mimicry or acceptable hydrology standards. That is: what is acceptable hydrology, or what is hydrologic mimicry? We’ll use the term “acceptable hydrology” from here on out. The reason is that often some theoretical “predevelopment” value may not be the right landing place either, because the streams have already adjusted to a different baseline or because such attainment is an order of magnitude more expensive and difficult than a slightly less onerous one with only marginal benefit. Whether this can be allowed in a regulatory setting should be a matter for local exploration and negotiation.

So, we need to find a replacement variable for the depth/percent criterion that is comparatively simple to understand but better reflects the desire to attain acceptable hydrology and without the shortcomings. In addition, there is a desire to mimic the natural response across a range of rainfall and inter-event dry periods.

Because the hydrologic cycle typically has annual repetition (with variability), a parameter that reflects an annual period may be preferred. Because, as a measure of hydrology at its simplest, we are interested in the ratio of runoff to rainfall, we can center focus on the annual ratio of runoff/rainfall–commonly termed the annual Rv or just Rv (with the understanding that this is an annual, not per storm or seasonal, expression of the ratio).

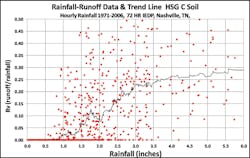

Figure 1 shows the result of continuous simulation of hourly rainfall for Nashville, TN, from 1971 through 2006 for a relatively flat site with Hydrologic Soil Group (HSG) C soil plotted against the storm Rv value. Most soil in Nashville is C or D soil. Reasonable values were chosen for the key variables and sensitivity analysis done. In this simulation, 15% of the rainfall ran off, 46% was removed through evapotranspiration, and 38% infiltrated.

Figure 1 also shows the great scatter in the data, where the same total storm rainfall can yield very different results depending on the rainfall distribution in time. The trendline is almost meaningless except to indicate a sort of moving average. For example, the 1-inch storm (the Tennessee design standard) event can yield zero runoff to 30% runoff. The trend line shows that, on average, runoff begins in earnest just below the 1-inch storm.

On an annual basis the accumulated Rv value for all storms was 0.154. That is, over the period from 1971 through 2006 our modeling estimated that about 15% of all rainfall ran off. This would reflect a well-manicured and somewhat treed Nashville backyard with maximal sheet flow.

The decision concerning the target value balances a number of factors, including relative current development types, densities, and ages; stream condition and ability to meet designated uses; conditions of similar streams but with different land uses; types and distribution of soils; presence of bedrock and the predominant mode of discharge for infiltrated flow; and other variables such as slope that may play into characterizing the hydrologic response of the area.

In Nashville, nearly all the soil is C soil, and the downtown area is combined sewer. Thus the largest portion of the land use is residential, and Nashville is noted for its many large yards. In many places a layer of bedrock lies sufficiently near the surface to cause much of the infiltrated rainfall to quickly find a rock seam or interflow channel and return to stream flow within a day or two. The streams in the suburban area of the city are generally stable and seem to have adjusted to the predominant land use, which is fairly low-density residential. Choosing the lower end of the density at 20% disconnected impervious area, the overall annual Rv is 0.20, creating a trendline only slightly higher than that pictured, especially in the range of rainfall amounts that do most of the work and carry most pollutants: 0.5 to 1.5 inches (Pitt 1999). This value was chosen as the target value for all new development and redevelopment–it was defined as “acceptable hydrology” for the Nashville area. That is, if through the use of green infrastructure a development can mimic very-low-density disconnected impervious residential land use, the stream impact will be minimal if any, and pollutant removal will be well within acceptable ranges.

If the soil varied across the different HSGs, a different approach might have been used where an Rv was assigned to each of the predominant groups and new development would need to develop a soil-weighted individual site target. Redevelopment might be treated differently with incentives provided (such as a higher Rv target) to encourage reuse of previously developed land rather than sprawl.

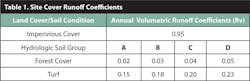

Basic Land Uses. Now the basic target has been set: The land-cover weighted average annual Rv for the site must be less than or equal to 0.20. The next step is to establish Rv value estimates for other common land uses. This is similar to establishing Rational Method C factor or SCS Curve Number estimates for different land covers. And the weighting process follows that pattern somewhat as well.

To determine an acceptable Rv value (or values), experience elsewhere was used to help to inform the simulation modeling because there was little or no date to calibrate the models. Several sources were used, including data from the Chesapeake Bay studies (Chesapeake Storm Network). A study was made of Nashville soils and statigraphy to determine standard types of situations. Some values were adjusted to help create a stronger incentive for the use of that land-cover type. Table 1 shows the design table that was derived from the analysis.

You will notice that this is a departure from the older Rv calculation methodology that considered only impervious area in the equation. When total suspended solids (TSS) loading was key, the data available plotted TSS loading versus impervious cover, and this was considered sufficient discrimination. When volume removal is the name of the game, then the type of non-impervious land cover is as important as whether it is pervious or impervious. The older Rv approach does not distinguish soil type nor non-impervious land cover and thus cannot create an inherent incentive to value these differences on a site.

This difference serves as a strong incentive to conserve or restore urban forest areas where possible as a specific and quantifiable GI practice (GIP). For example, for a site that is 40% impervious:

For C soil and turf: Rv= 0.6 * 0.2 + 0.4 * 0.95 = 0.50

For C soil and forest: Rv= 0.6 * 0.04 + 0.4 * 0.95 = 0.40, a 20% reduction

Values on the lower end of each HSG type were used for simulation purposes. “Forest cover” assumed that the soil beneath the forest cover was natural forest duff and not turf.

Green Infrastructure Practices. The next step is to develop Rv values for various practices that could be employed on the site to reduce the overall site Rv below 0.20. The idea is that, for example, an impervious area with an Rv of 0.95 could have the Rv reduced by discharging the runoff through a GIP. When this is done the impervious land use takes on a different Rv value commensurate with the actual Rv value of the combination of the impervious area and the GIP.

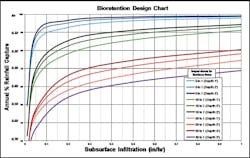

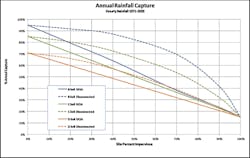

As was done for Table 1, a combination of experience elsewhere plus the result of continuous simulation informed the decisions. It is impracticable to expect every designer to employ continuous simulation for every design, and for staff to perform a rigorous review of such designs. Instead, the simulation can be done for a range of key design parameters and plotted simply. For example, Figure 2 shows such a plot for the design of bioretention or rain gardens.

To develop the figure, a range of subsurface infiltration rates, media depths, and ratios of impervious area to bioretention surface area were used. The simulations can proceed very quickly moving across the range. Patterns emerge allowing for graphic design chart construction. In Figure 2 it can be seen that, for any desired Rv and known subsurface infiltration rate, a bioretention size can be determined without calculation. The value chosen is the value that would have been derived from complex continuous simulation.

Suitable safety factors can also be added to the chart or to the design process. For example, some communities require the measured infiltration rate to be reduced by a certain multiplier. Others require an elevated underdrain system to be installed such that if the bioretention begins to clog, the discharge will still be filtered through the soil media and the result discharged through an outlet pipe to the downstream system. Figure 3 shows such a system. Studies have shown that for areas without significant deep infiltration capability, the outflow hydrograph from such an arrangement can well mimic the interflow characteristic of a natural system.

In Figure 2 the interrelationship among the various design variables can readily be seen. For example, it is not possible to obtain an Rv for the impervious area–bioretention combination less than 0.20 at a ratio of drainage area to surface area above 20:1 unless the subsurface infiltration rate is high. The figure also shows a precipitous dropoff of capability of the pond at infiltration rates below the 0.20- to 0.25-inch-per-hour range. In this case it might be wise to require the use of underdrains at any measured infiltration rate less than that.

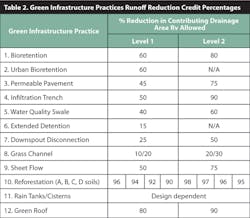

Rv values for Nashville were developed for a suite of GI practices. The practices include standard structural approaches and also a set of more natural approaches that have more to do with landscaping, soil amendment, and tree planting than engineered practices. Table 2 shows the set of practices included in the Nashville approach.

Each practice has at least two levels of allowable Rv reduction for the contributing drainage area. The levels have been set in recognition of more advanced design practices that can better ensure consistent and long-lasting volume and pollutant removal. Refer to the design manual for more details. It was decided here not to directly use the continuous simulation data for design as shown in Figure 2 out of concern for a lack of actual performance data. However, to provide more flexibility in design, such use can be easily accomplished even with the safety factors as expressed in Table 2.

Design Process. The next step in criteria development is to fold the different practices into an overall design process that will maximize the use of more natural GIPs. The calculation approach is as simple as that of calculating a weighted Rational Method C Factor or SCS Curve Number. It is, in fact, the calculation of a corresponding volumetric runoff coefficient.

The design process can then be laid out to ask the designer to step through a site design first considering the actual site layout itself in terms of reduction of runoff impacts and integration of green infrastructure considerations with all the other concerns of site development.

Secondly, the runoff that does occur can be routed to and through natural or green areas, greatly reducing the volume of runoff at very low cost. For example, Figure 4 shows the impacts of simple disconnection to the turf area downstream from an impervious parking lot for the three predominant soil types in Nashville. In this figure the percent imperviousness of the parcel was increased with that impervious area sheet flowed over the remainder of the parcel area. So, for example, if the parcel is 70% impervious, that impervious area runoff is sheet flowed across the remaining 30% of the rectangular lot. The straight lines show the runoff for the total parcel if the impervious area is directly connected instead. The vertical axis is percent annual capture, which is equal to 1-Rv. For B soil, for example, if the 50% impervious area of the site is simply routed across the remainder of the turf, the difference in annual capture is 28%–and the Rv for that impervious area goes from 0.45 to 0.18 (55% to 82% capture), meeting the Rv standard without a single structural control except a flow spreader and careful site grading.

The third step, if the other two do not achieve sufficient runoff reduction is the design of structural controls.

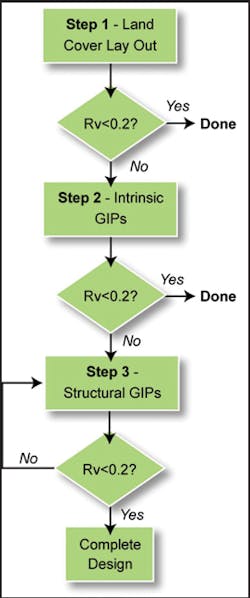

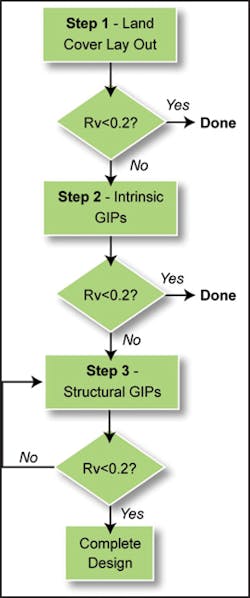

The steps, illustrated in the flow chart in Figure 5, are described in the Nashville manual.

Step 1: Reduce Runoff Through Land Use and Ground Cover Decisions. This step focuses on the “background” land cover and how much rainfall it removes from runoff. Design activities in step 1 focus on impervious area minimization, reduced soil disturbance, forest preservation, etc. The goal is to minimize impervious cover and mass site grading and to maximize the retention of forest and vegetative cover, natural areas, and undisturbed soils, especially those most conducive to landscape-scale infiltration.

Calculations for step 1 include the computation of volumetric runoff coefficients (Rv) for land use and HSG combinations (including impervious cover). Site cover runoff coefficients are shown in Table 1.

Step 2: Apply Nonstructural GIPs. If the target Rv £ 0.20 has not been attained in step 1, then step 2 is required. This step focuses on implementing the more intrinsic GIPs during the early phases of site layout. In this step the designer enhances the ability of the background land cover to reduce runoff volume through the planned and engineered use of such practices as downspout disconnection, sheet flow, grass channel, and planned reforestation. Each of these practices is assigned an ability to reduce a storm of moderate intensity, and this assignment is conveniently captured in the Runoff Removal Credit or the RR Credit. RR Credit values for nonstructural GIPs are shown in Table 2.

Step 3: Apply Structural GIPs. If the target Rv £ 0.20 has not been attained, step 3 is required. In this step, the designer experiments with combinations of more structural GIPs on the site. In each case, the designer estimates the area to be treated by each GIP to incrementally meet the overall runoff reduction goal. Such engineered practices as infiltration trenches, bioretention, green roofs, permeable pavement, and rainwater harvesting are envisioned. Design and sizing standards have been created for each of these GIPs to ensure their ability to meet the 1-inch volume capture still required after steps 1 and 2 have been implemented. RR Credit values for structural GIPs are also shown in Table 2.

At the end of step 3, the designer must have achieved the standard by attaining an area weighted Rv value of 0.20 or less. In some places the runoff reduction approach is integrated with the current 80% TSS capture standard as a fallback provision.

Final Adjustments. As in any approach, the framework should be tested for potential inconsistencies or loopholes that may be exploited by wily designers. Admitting to being such, and knowing others (some of you, no doubt), we looked at application of the method across a suite of real and imagined sites.

Two immediate concerns were raised. The first is that this approach has the advantage in that attainment of the Rv maximum value can, in some cases, allow for small impervious areas to be untreated. This keeps sites from having to design many small and generally ineffective practices in favor of focus on reducing actual impacts. The down side, for very large sites, is that significant impervious areas could be constructed without treatment.

This was remedied in two ways. First of all, there is a statewide buffer requirement. No impervious area is allowed to discharge directly into waters of the state without flowing via sheet flow across at least the minimal buffer width of 30 feet. Second, no impervious area that is large compared to the upper end of the receiving waters can be constructed without treatment no matter the Rv for the whole site. For example, a large golf course desired to construct a new clubhouse parking lot. Using the whole course as the “site” meant they did not have to do anything to treat the water. Supplying a maximum allowable impervious surface without treatment can remedy the situation.

A second developer-raised issue with volume-based approaches is the fact that flood control must normally still be done. Developers desired a way to reduce the flood control volume to take credit for the GI volume removed. A simple approach is to calculate a modified Curve Number, which can be done by first calculating the SCS runoff volume for the design storm from the SCS equation:

Q = (P — 0.2 * S)2

(P + 0.8 * S)

Q is the runoff volume in inches, P is the 24-hour storm depth, and S is expressed by:

S = 1,000 — 10

CN

The captured volume is then subtracted from Q to form an adjusted Qadj (all expressed in consistent watershed inches) and an adjusted Curve Number (CNadj) is then calculated as:

CNadj = ____________1,000_________________

10 + 5P + 10Qadj — 10(Qadj2 + 1.25QadjP)1/2

The Snappy Close

In these two articles we have tried to point out some inconsistencies in the usual way that green infrastructure is sized. These inconsistencies sometimes lead to oversized or poorly conceived designs. Their dependence on instantaneous volume capture can lead to a purely structural solution when a combination with natural areas will often work better and at lower cost.

As communities face the long-overdue reissuance of their MS4 permits and seek to find ways to bring their communities into the world of sustainable site design through green infrastructure, we believe that the advantages of this method will make that transition easier, sites more thoughtfully designed, and systems more accurately sized to do the job they are meant to do.

Let’s take a minute and assess this proposed approach against the seven objective evaluation criteria above.

- The method has been accepted by the state of Tennessee as meeting compliance with its state standard and is being investigated by several other states and local communities.

- The method, by definition in its use of annual Rv, mimics the hydrologic runoff response of the established base condition. And it can be tailored to local conditions and even the variations on an individual site rather than being a one-size-fits-all approach. However, the variation between evapotranspiration and infiltration (and alternative runoff use) will change depending on the treatment options selected. For example, for the scenario of HSG C soil converted to 100% impervious with bioretention designed for the 95% storm capture, the distribution changes from 15% runoff, 46% evapotranspiration, and 38% infiltration to 14% runoff, 22% evapotranspiration, and 64% infiltration.

- Being an annual parameter it intrinsically recognizes the inter-event dry periods throughout the year.

- In use in many local projects, the method has been proven to be understandable and simple in application yet yields effective results. In Nashville the developer has the choice of using this method or the older TSS-reduction method. The majority are choosing this approach over the older one.

- The method highlights and stresses nonstructural approaches ahead of structural ones. It does recognize and reward the use of more pervious or retentive land covers—not simply distinguishing between paved and unpaved. It encourages, in the three-step process, the early consideration of natural vegetative practices in the initial site layout.

- The ability to perform long-term maintenance is still to be proven—but then that is the same for almost all GI practices and programs. Life cycle costs and ROI are the same for these GI as for others. The data are mostly positive but mixed.

- And finally, known loopholes have been closed—though no guarantees that more will not be found!

There will be other methods coming along in the next few years, maybe better ones. Certainly things presented here can be improved on. This is only an initial set of ideas woven together into a coherent package—one that has proven to be both understandable and acceptable to developers.

Add your ideas and insights to the conversation, and make improvements. Maybe we’ll converge on the best answers just in time for the next stormwater design paradigm to come along.

References

Pitt, R. 1999. “Small Storm Hydrology and Why it is Important for the Design of Stormwater Control Practices” in Advances in Modeling the Management of Stormwater Impacts, Volume 7 (Ed. by W. James). Computational Hydraulics International, Guelph, Ontario and Lewis Publishers/CRC Press.

Chesapeake Stormwater Network, Technical Bulletin No. 4, Technical Support for the Bay Wide Runoff Reduction Method Ver. 2.0.