Football Becomes America’s Biggest Water Sport

Hundreds of workers clad in their safety gear, hardhats, and reflective vests are seen on the corner of Marie P. DeBartolo Way and Tasman Drive in Santa Clara, CA, the site of a just-completed stadium project. Public affairs staffers and security personnel in dark-toned business attire wield warlike talkies and direct visitors over dirt and gravel construction access roads to various virgin parking lots; a crumbling sound is heard under the wheels. The stadium, viewed from the distance of the freeway approach, dominates the landscape, but close up, though imposing, it nonetheless conveys a welcoming presence, alive with the red and gold color scheme signifying that this is the new home of the San Francisco 49ers.

Inside, along with the brilliant green turf lit by the summer sun, the stadium augments its color scheme with an additional hue: to be specific, a brand new LEED (Leadership in Energy and Environmental Design) Gold Certification.

Under a cloudless July sky, the absence of moisture in the atmosphere during northern California’s disconcerting long-term drought does little to dampen the festive mood of the occasion; it’s the ribbon-cutting ceremony for Levi’s Stadium, the first NFL stadium to win LEED Gold Certification for new construction, and a venue its owners hope will help inspire the entire sports community to embrace the ethos of sustainability—not just for play, but for all of the social ramifications.

The San Francisco 49ers Levi’s Stadium;

The drought itself was part of the inspiration for the stadium’s major investment in water efficient infrastructure. Now some of the results of that investment will be on display to the world on any given Sunday during football season.

All Sports Are Watersports

Allen Hershkowitz, senior scientist and director of the Sports Greening Project at the NRDC (National Resources Defense Council) and co-founder of the Green Sports Alliance, agrees it was an impressive venue, adding, “We just held our summit out there at Levi’s Stadium.”

In fact, Hershkowitz says Levi’s Stadium had just announced their connection with Santa Clara’s municipal water recycling infrastructure, taking water that had been used at least once somewhere in the city to use again for nonpotable uses at the stadium, a major milestone in their water efficiency plan.

Hershkowitz views the sparkling new LEED Gold Levi’s Stadium as the gleaming tip of the iceberg in terms of the greening of the sports industry. “The thing is there are so many examples in the baseball, hockey, and basketball arenas —there’s a huge shift towards water conservation initiatives at professional sports arenas as a result of the sports greening movement that is taking over the world,” he says.

Water is a key part of any stadium’s operations he says. “There’s water used for cleaning, water used for concessionaires stands. At hockey arenas, water is used for making ice; water is used for the heating and cooling of buildings, for landscape maintenance, for consumption by fans, food preparation, and for beverages. It’s pretty fundamental. As in life, more broadly, it’s pretty fundamental to the operation of sports facilities.”

He says that NRDC’s Green Sports Alliance advises more teams than anybody else on sustainability initiatives, and “Water is used in so many ways that a water efficiency audit is really one of the first things that we recommend.”

He continues by saying that the math is simple: “Measure where the water is used, and how much is being used and invariably—in my experience—whenever that is done, there are always opportunities identified for water conservation.

“At Staples Center, I remember we did an energy efficiency and water efficiency audit of that arena. We were walking around that venue and identified that there were 178 urinals each of them using 44,000 gallons of water a year, so they switched to waterless urinals saving about $6,000 in water and effluent costs and conserving about 1,000,000 gallons of water a year. That’s a basketball and a hockey arena. You’re seeing more and more of that.”

After the audit Hershkowitz says the next step is to “do the ROI [return on investment].”

This evaluates “How much are you spending on water now, versus how much it would cost to install low-flow or waterless fixtures, and then what’s the payback in terms of water cost savings. We find that payback happens pretty rapidly.

For infrastructure facilities that are going to last for 10 years—an arena or a stadium is built for 30 years–putting in something that has a payback of one year or three years is very often very cost-effective because you’re going to be using that infrastructure for another 10 or 20 years.”

If one were to miss the discreet placards pointing out water efficient fixtures in Levi’s Stadium restrooms, billboards at the stadium don’t offer a reminder. Water savings won’t appear on the scoreboard, and sports announcers are highly unlikely to mention water saving measures during the post-game wrap-up. However, Hershkowitz believes it’s not a message that needs to be shouted.

“If people show up, and they see the waterless urinals, they can get the picture,” he says. But Hershkowitz adds that fans are not the only ones watching what happens on the field. “Really, I think the Holy Grail of sports’ influence is the supply chain. Every industry meets on the professional football field—the water industry, the energy industry, the beverage industry, the food industry, the textile industry, the paper industry, the chemical industry—all of these industries are either vendors to professional sports or sponsors of professional sports. So when Levi’s Stadium or other stadiums put in infrastructure to change the way they acquire and use water, that’s noticed by the supply chain. The companies that are installing that technology start to grow, their market penetration grows, and the sponsors of the teams start to notice. And they often represent major corporations, so it’s not only influencing fans, but they are also influencing the supply chain.”

Santa Clara’s Mayor Jamie Matthews says local priorities drove the idea of building sustainability into the stadium.

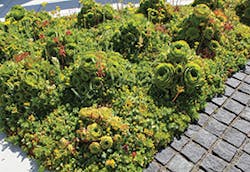

Details of green roof with a view, Levi’s Stadium

“The values of Silicon Valley and our area demand it,” he says. “All of us understand collectively and individually that environmental sustainability is critical for health and for the future. You can’t build a building like this without thinking about the potential impacts.”

With the city a key partner in the public/private partnership that built the $1.3 billion project, Matthews touted the stadium’s massive investment in solar arrays, designed to collect enough power so that “the stadium is net neutral during games,” sustainable sourcing for materials such as concrete, the “100% American steel” used in construction, and ample accessibility to mass transit options such as Amtrak and BART commuter rail systems.

Although Levi’s Stadium is the first entirely newly constructed NFL ballpark to achieve LEED Gold certification, Baltimore’s Raven’s M&T Bank Stadium achieved LEED Gold for retrofits a year prior; the oldest league Stadium, Soldier Field, home of the Chicago Bears that first opened in 1924, achieved LEED certification for some new construction; and Lincoln Financial Field, where the Philadelphia Eagles play, arrived at LEED Silver for Existing Building in 2013. In all, four NFL stadiums have achieved some level of LEED Certification.

Shutting Down the Running Game

Despite the intricate choreography, planning, and almost balletic performance on the field, in football there is always an element of improvisation that comes into play when an unforeseen formation or lineup requires an on the spot adjustment in strategy. In such circumstances, the opposing team’s captains often snap new instructions to their teammates. Shouting coded audible instructions, the opposing squads adjust their positions to counteract the emerging realities they’re seeing on the field just before the scrimmage.

And the ability of a well-oiled team to innovate on the fly sometimes leads to spectacular crowd-pleasing results.

Inside, Levi’s Stadium displays an atmosphere of sustainability.

Jeff Provenzano, Director of Operations—Camden Yards Sports Complex that includes Baltimore’s Ravens M&T Football Stadium says implementing water efficient practices can also call for strategic adjustments on the fly and the results can be impressive.

Something along those lines happened during Provenzano’s first weeks on the job at Raven’s MMT Stadium. “It was an off

day, a Saturday,” he says, “I walked into the stadium—it was very quiet; there was nobody there. That’s when you can hear things in stadiums, when there’s nobody there. And I started hearing a whole lot of water coming down the drainpipes—you could just hear it while you were walking around. So I picked a riser, and I started following it up—and it turns out that after any given football game we could have anywhere from a half dozen to maybe a dozen, or more, urinals that are continually flowing. By the end of the game, they have been hit so many times that the plunger gets worn, and they would just continually run.”

He asked about it. Being told, “‘We’ll get to it before the next game,'” he realized, “Well, that could be two weeks—that could be 10 days—so for 10 days, were we going to let these urinals run all the time?”

Provenzano made an operational decision that at the end of each game, “When the building was calm and everybody was out of the stands, a crew would walk every restroom just to make sure nothing is running, and if it was running, we’d shut it down. Tag them and bag them, and come back and fix them, and just don’t let them run for days at a time.”

He says it might not have been a very popular decision with staff eager to go home at the end of a long day, but it doesn’t take more than an hour, and everybody participates, including himself.

It’s now become a standard procedure after the game to make the radio call.

“If I’m on the deck, I’ll respond, ‘I’ll take the lower deck, or I’ll take this section’—and there are about seven or eight of us—we walk every restroom.”

In addition to operational changes, Provenzano switched out some hardware. He had waterless urinals installed, provided by a variety of manufacturers throughout the facility.

He also had dual-flush toilets installed, first particularly for the women’s restrooms. Although signage explains their function, he says it’s rather self evident to customers what they do. To illustrate, he says he recently led a tour group of about 50 women showing off the stadium’s features, and when he got to that part there was a bit of levity, but his guests instantly understood the concept without the need for a philosophical explanation.

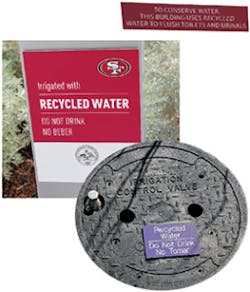

Levi’s Stadium makes ample use of recycled water.

“It’s up for one, down for two,” he says. “As soon as you bring it up you see all the hands go up—they all know what up is and down is.”

With the relatively low-cost dual-flush retrofit, at around $100 each, including labor, Provenzano then installed similar fixtures in the men’s room, too.

“There’s no harm, no foul if they hit the wrong direction, and if you use it the way you’re supposed to, you use half the water,” he says.

Team locker rooms have always been considered practically sacrosanct, but with dozens of players celebrating their victories or assessing their improbable defeat with unhurried post-game showers, it’s not difficult to imagine the opportunity for water savings that could be achieved there as well. However, Provenzano guessed that tinkering around to find opportunities to promote water efficiency in the team locker room might come with the risk of triggering some angst among the players. He decided he wouldn’t let the possibility of a little grumbling serve as a deterrent; however, he thought it prudent not to make a big deal about the post-game substitutions he had planned. He instructed his installation crews to switch out the existing standard shower fixtures to Sloan’s low-flow alternatives, but to be discreet about it and not to broadcast to the players news of the pending change.

The athletes turned out to be a bit more resilient than might be expected, and the change was likely little noticed. Provenzano said out of “around 70 or so players on the pre-season season squad, only one voiced any complaint” about the upgraded facilities and that was only after a direct survey soliciting players’ opinions some time after the change.

Practicing water efficiency has also helped Provenzano learn more about the venues he operates. During a recent routine maintenance operation at the Oriole’s baseball field he had the occasion to peer down into a Camden Yards drainpipe and noticed a large volume of clear potable water had been entering the drainage system, even on days when no events were scheduled.

Contemplating the possible source of the wasted water he said, contrasted with the ice air coiled ice machines at Raven’s Stadium, “I realized all the concession stand ice machines in Oriole Park were water coiled condensers. Every time someone turns on an ice machine the water starts running.” As a consequence, he’s thinking about phasing out the water-cooled ice machines in the near future.

Maintenance too offers opportunities for water saving. At a time when the complexes’ steam system was in need of some major work, Provenzano says, “The first thing I started to notice was water going down in the condensate, gushing down like a jet engine everyday.”

While he says Viola Energy supplies the steam, the facility has three tanks of its own used for storage, and they were having some problems. Provenzano brought in a contractor to do some maintenance and spent $100,000 dollars to fix all three tanks. That effort brought the condensate “down to a trickle—not only does it save on steam usage, yielding $120,000 less in steam usage, it paid for the project in one year.”

Provenzano says one of the biggest unmet challenges in water efficiency in large venues, such as ballparks and stadiums, is in housekeeping practices, particularly for cleaning up the stands after the event. Pressure washing the stands, as done at his facilities, uses less water than a simple hose down, which relies on volume alone. He’s working to put together a training program to encourage staff to practice greater water efficiency when they use pressure washers.

Nonetheless, he says there is no absolute requirement that pressure washing with water be the standard practice. “They could sweep with a broom; it’s already pretty clean to begin with.”

Provenzano admits he was not always such a big proponent of sustainability. His interest blossomed from a chance occurrence several years ago, when, one day, he received an e-mail from a lady, with a picture attached. The picture, which he says was probably taken from a passing vehicle, showed the facility’s irrigation system running on a day that had delivered more than an inch of rain. “It was still raining when she took the picture,” he says, and the message asked, “Why are you running your irrigation system at the same time it was raining?”

“A very good question,” thought Provenzano.

Things changed drastically after that. His new irrigation policy, sensibly, started with watching the weather and sending out crews to shut down irrigation when the forecast or the skies looked like rain. Later, he graduated to installing a zoned irrigation system, adding smart irrigation as time went on. His landscape technicians and designers began planting more native species to completely avoid the need for irrigation in certain areas. Ultimately, he was able to retire some of the irrigation zones themselves. This attention to water efficient landscaping bubbled over into water efficiency in every area of operations and maintenance with big results.

“Right now we’re averaging about three million gallons a year we’re saving down there,” he says.

Even though Provenzano says the prospect of going after LEED Gold Certification was not even on his mind when he began implementing water efficiency measures at the venues, over time, through tweaking maintenance, operational procedures, and system upgrades, things added up, and in 2013, Baltimore’s Raven’s Stadium became the first NFL Stadium to achieve that designation, a lot of it improvised.

Keeping Score

Scott Jenkins, Chairman of the Green Sports Alliance, is now working on plans for building the new Atlanta Falcons Stadium, having previously run Safeco Field in Seattle and Lincoln Financial Field in Philadelphia, both venues with a track record for sustainable practices, with Lincoln Financial Field obtaining LEED Silver towards the beginning of the 2013 football season. In his view, general maintenance is an important key to efficiency.

“If you have irrigation systems that aren’t properly maintained, you can waste a whole lot of water—if you have drippy faucets or other equipment that’s not running properly, it can be extremely wasteful,” he says. Regarding maintenance, he says keeping a running tab on water usage can be critical.

Jenkins recommends installing a utility dashboard to track water usage in real-time. “In Seattle, we worked with a company called OSI Soft to put in a dashboard for electric, gas, and water. And when we first installed the dashboard we found that we had a problem during maintenance where a valve hadn’t been shut off, and we had an unusual amount of water being used at a time when we shouldn’t have. If we didn’t have the visibility of the utility dashboard, we would not have known that, and we would have gotten really high bill the next month and been scratching our heads trying to figure out why.”

Still in the design phase, Jenkins current big project, building the new Falcons Stadium in Atlanta, has not yet selected its vendors for water infrastructure; nonetheless, he anticipates building in practices and technologies to make sure water gets used wisely. In places like California and the Southwestern states, he says, “Water is an issue;” this is likewise in Atlanta. Considering the new stadium, he says, “We’re looking to do as much as we can around water, but it will have high-efficiency fixtures for sure.”

Making the Final Cut

AEG, one of the world’s leading companies managing sports arenas and entertainment venues of various types, has found that water efficient practices can yield incredible results in a short time-span. The company, which manages the Staples Center in Los Angeles, and where they house their North American Operations, recently issued their third biyearly sustainability report.

The report states that the company has achieved an impressive 30% reduction in water use per attendee across its portfolio of 77 venues that it manages, surpassing its projected goal of achieving a 20% reduction in water consumption per attendee by 2020, according to the firm’s sustainability report.

Also, according to John Marler, Senior Director of Energy and Environment for AEG, the company achieved this result in two ways: by building bigger audiences—thus distributing fixed consumption over a much larger customer base—and through enhanced water conservation measures, themselves.

Waterless urinals, supplied by companies such as Falcon and WaterFree, grace many of the restrooms at AEG’s venues, and Marler expects the trend to continue, leading to waterless urinals in more public buildings and commercial establishments as people become accustomed to technology they might first encounter at large entertainment and sports venues.

He says as AEG expands its knowledge base about waterless urinals, it is becoming easier to promote their use at the wide range of venues under AEG management. The company started installing waterless fixtures in its venues in 2009, and since that time has not run into any problems with odors or deleterious effects on plumbing. But, he says, it is nonetheless important to address these concerns, and his company’s experience doing so helps when they promote the idea among affiliates.

Marler says AEG is currently planning a major retrofit for one of the NFL’s iconic stadiums, the Oakland Coliseum. Built during the 1960s, an era when there was no shame in being oblivious to water scarcity or dwindling supplies of any other resource, it has features one would be hard pressed to find in a more modern facility. There are fans who praise its vintage trough-style urinals. Running constantly, there’s no need to wait in line, they can just sidle up and get back to the action on the field. However popular, deciding whether that traditional approach will make the cut will become one of AEG’s upcoming challenges.

Despite noteworthy initial results, Marler says, “Short of asking people not to use the restrooms,” there is a finite limit to what can be done on the consumption side to cut back on water usage. However, he says the next step to enhance water efficiency is to find new water sources and a good place to focus is enhancing opportunities to use reclaimed water.

Alan Hershkowitz of the Green Sports Alliance agrees. “There’s no reason to be putting drinking water down the toilet, no reason to be putting drinking water down a urinal. Water reclamation is fundamental to help us avoid wasting drinking water in toilet fixtures.”

Greening the Sandlot

Recycled water will account for about 85% of all water used in San Francisco 49ers Levi’s Stadium. It will go for purposes of playing field irrigation, a 27,000-square-foot green roof, flushing toilets, and cooling tower makeup water. Inside, the stadium is dual-plumbed with recycled water used for toilet flushing and potable water used for hand washing, concessions, and locker room showers.

Advanced technology will play a role, too. Like Safeco Field in Seattle, the San Francisco 49ers Levi’s Stadium has built-in efficient tracking mechanisms to monitor energy and water use. Brightworks Sustainability advisor Heath Blount, who worked on the design for the stadium, says his company, engineers from NRG who outfitted the facility’s solar arrays, and HNTB architects worked with the owners to develop an understanding of how to best track the energy and water use within the facility.

“We worked with them to make sure that infrastructure was in place,” he says. “It’s not really revolutionary—we used modern industry standards, and used it as efficiently and effectively as possible, with a lot of controls. For instance, if people in the suites open their windows or the doors, the air-conditioning shuts off automatically, because the outside conditions are OK.”

The turf itself comprises of a special Bermuda grass seeded to a polymer substrate, which can survive on half the water a traditional natural turf grass field would require.

And Tambra Thorson, senior interior designer on the project, says the stadium will take advantage of Santa Clara’s recycled water supply for stadium washdown operations, resolving a potable water quandary experienced at facilities where reclaimed water is not yet available.

When the news spreads that Levi’s Stadium is making such practical use of reclaimed water, Hershkowitz says other cities will “take note and say ‘Oh boy, can we do that, too?'”

He continues, “Is sports going to save the world by itself? No, no single industry can, but the platform, the cultural and market visibility arguably exceeds that of any other industry. Just walk out of your office, and look at how many people are wearing baseball caps or some sports jersey. The film industry is very influential, [and] the music industry is very influential, but I daresay there are more people walking around with sports apparel on, than shirts about films or about their rock stars.”

Hershkowitz views the sports greening movement as becoming pervasive—not just in professional ranks, but also throughout collegiate athletics. Beyond that, he envisions an even bigger goal.

“This movement is only eight years old with thousands of venues around the world, so it’s going to take us a little while to take it to high school and little league, but that’s what we want to do.

“Half the planet—three billion people—don’t have adequate water supplies; scarcity is a gigantic global urgent ecological issue, and the sports industry is among of the most culturally visible and market influential industries in the world. It’s over a $450 billion industry, and it’s not political.”

Hershkowitz is enthusiastic for green sports’ prospects. “You get the message out without being political about water conservation–remember, only 13% of Americans say they follow science, 63% say they follow sports. In terms of the cultural visibility of water conservation at sporting venues, there’s a lot of bang for the buck.”

As a crowning achievement, the Levi’s Stadium will host Super bowl 50 in 2016 at the greenest professional sports facility in the world.NRDC held a retreat at the home of one of its trustees in Sundance, UT, in 2009, says Allen Hershkowitz, senior scientist and director of the Sports Greening Project at the NRDC.One of the topics of discussion was figuring out how to reach masses of people with regard to messages on global warming and environmental stewardship in general. Meeting host, Academy Award winning actor, and noted environmentalist Robert Redford suggested working with sports. Hershkowitz explains: “It was Bob Redford’s idea” to reach out to “people who go to baseball games and football games. We need to affiliate with non-traditional allies. “I wrote a letter to the Commissioner of Baseball Bud Zelig.

It turns out Bud Zeilig is a great environmentalist, arguably the greatest environmentalist in the history of professional sports. He invited me in to talk about working on environmental issues in baseball, and I became the environmental advisor to Major League Baseball, which I am right now.” Later, Hershkowitz became the environmental advisor to the National Basketball Association, the National Hockey League, US Tennis Association, Major League Soccer, and NASCAR.

Receiving a call to work with entrepreneur and sports franchise owner Paul Allen and Vulcan Inc., in Seattle and Portland, Hershkowitz helped found the Green Sports Alliance, serving on the executive committee of that board.

Hershkowitz says, “Water scarcity is going to rival sea level rise as one of the consequences of global climate disruption. Water scarcity is a global problem: India, Africa, China; in the Southwest USA it’s inevitable. Lake Mead, which supplies all of the water to Las Vegas, is at its lowest level since records started being kept over 90 years ago. The Colorado River no longer reaches the Pacific Ocean, and 30 million people in the USA and Mexico depend on the Colorado River for their water supply.”

But he believes raising awareness and taking action can help address these issues.

The Green Sports Alliance describes itself on its website as “a non-profit organization with a mission to help sports teams, venues, and leagues enhance their environmental performance. Alliance members represent over 230 sports teams and venues from 20 different sports leagues. Since February of 2010, the Alliance has brought together venue operators, sports team executives, and environmental scientists to exchange information about better practices and develop solutions to their environmental challenges that are cost-competitive and innovative.”

More information about the Green Sports Alliance is available via http://greensportsalliance.org.