“You Created a Stormwater Utility in the Midst of the Great Recession? You Must Be Crazy There in Salem!”

The Public Works Department of Salem, OR, provides residents with a full suite of stormwater services that includes stormwater system operations and maintenance, stormwater monitoring, street sweeping, public education, stream cleaning, spill response, master planning, regulatory compliance, capital project delivery, in-stream monitoring, flood early warning systems, and much more. Salem’s stormwater collection system consists of more than 85 miles of open channels and ditches, 90 miles of waterways, 420 miles of pipe, 800 detention basins, and 22,000 storm drainage structures.

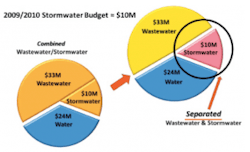

Historically, Salem’s stormwater services have been funded by the city’s wastewater ratepayers. However, wastewater rates—which are largely determined by drinking water consumed during the rainy season—have no relationship to the impacts a property has on the stormwater system. Beginning in late 2009, the Public Works Department began working on a proposal that would decouple stormwater funding from wastewater fees by creating a stormwater utility and funding the stormwater services with a separate stormwater fee. An extensive public outreach effort was conducted during the 12-month period leading up to City Council’s vote in December 2010. Public Works staff presented the proposed utility at more than 60 public venues. Two work sessions were conducted for city councilors, and the public hearing spanned two council meetings. On December 6, 2010, the council approved creation of a stormwater utility and implementation of a stormwater fee.

Deep into the Great Recession and during a period when other stormwater utilities around the country were being successfully challenged by voters, Salem was successful. In large measure, this success was due to the public outreach effort that engaged city staff with key stakeholders in a vigorous exchange of ideas and proposals. It is noteworthy that the final recommendation that went before the City Council in December 2010 had changed significantly from the proposal first presented to the public in January, changes that were a direct result of feedback received during the outreach period. In a Statesman Journal editorial on December 12, 2010, the newspaper noted, “Overall, taxpayers are the winner because, in many ways, the city’s handling of this issue has exemplified local government at its best.”

Written from the perspective of city staff, this article summarizes why we chose to create a stormwater utility, describes where we started and how we ended up, and concludes with a selection of lessons learned.

Why a Stormwater Utility and Why Now

Salem City Council’s approving vote in December 2010 was not the first time the council had considered a stormwater utility. Public Works staff first recommended a “storm drainage” utility to the council in February 1983. This first proposal presented nine alternative service levels and provided a cost per equivalent service unit (ESU)—one ESU was 2,400 square feet of impervious surface—ranging from $1.60 to $4.30 per month. The staff recommended a monthly charge of $3.60 per ESU, which would fund maintenance and other programmatic activities at approximately $1.0 million per year and provide an additional $1.5 million in stormwater capital construction. At the September 26, 1983, public hearing “a storm of opposition . . . burst on the Salem City Council” when 55 opponents to the proposed fee packed the Council chambers (Statesman Journal 1983a). In an editorial on October 3, 1983, the Statesman Journal stated its opposition to the new fee, noting that “not too much time has passed since water and sewer bills were increased a stunning 66%” (Statesman Journal 1983b). In a placatory gesture at the end of the op-ed piece, the paper concluded that while “the drafters of the plan put together a fine proposal . . . the community cannot afford to do everything at once” (ibid.). In November 1983, after several workshops and debates, City Council directed staff to put the storm utility on hold “because of the state of the local economy at the time and the level of service charge proposed” (City of Salem 1987).

Three years later, in December 1986, Public Works forwarded to the council a study recommending the storm drainage utility concept be reconsidered. In January 1987, the council appointed a subcommittee, consisting of the mayor and two councilors, to review the Public Works revenue requirements. In March of that year, the subcommittee completed its work and directed Public Works to return to City Council with a revised proposal. Public Works staff came back to the council on April 6, 1987, recommending a monthly fee of $0.75 per ESU. This level would provide for minimum maintenance service levels that would, for example, increase the ditch cleaning accomplishment rate from 4% to 47%. The $0.75 per month per ESU would also provide for an annual stormwater capital construction fund of $100,000. When Public Works proposed the $0.75 per ESU monthly rate, Portland’s stormwater rate was $0.92, Corvallis’s was $1.60, and Medford’s was $2.95 per ESU (City of Salem 1987).

The “Rain Tax.” According to Public Works folklore, tainted perhaps by the eventual outcome, there was very little effort made to involve the public during the period leading up to the City Council vote in 1987. On the day of the June 8, 1987, public hearing, Salem’s Statesman Journal ran a notice stating that the council agenda “includes 12 public hearings, including a proposal to have a used car lot at the junction of 12th and 13th Streets SE and a plan to charge property owners a fee based on the water that runs into the city storm sewer system from roofs and driveways” (Statesman Journal 1987a). At the public hearing, one letter was submitted into the record opposing the fee, and three residents spoke to the council, one in favor and two opposed. Deliberations were subsequently held in council chambers on June 15, 1987, and at the June 22, 1987, meeting, the City Council unanimously passed Ordinance Number 65-87 enacting Salem’s first stormwater utility. The vote was 7–0 (two councilors were absent). The ordinance would take effect on September 1, 1987.

It has been said that the term “rain tax” originated in Salem sometime in early 1980s, which may or may not be true. What is true, however, is that no matter the opinions (and there are many) regarding the concept of a stormwater utility fee, individuals who enjoy paronomasia—a fancy term for playing with words—tend to appreciate the topic.

One day after the June 1987 public hearing, the Statesman Journal ran with the headline “Renters say they’re getting soaked by city rain tax” (Statesman Journal 1987b). In the June 16, 1987, edition of the Statesman Journal, the paper reported on the results of the City Council vote with the headline “Council OKs rainwater tax” and concluded the article by saying, “Without the new tax, money for the city’s storm drainage system would dry up in less than two years, city officials have said” (Statesman Journal 1987c).

Not long after the council’s approving vote, a local real estate agent began collecting signatures from other soon-to-be disgruntled stormwater ratepayers, and the rain tax backlash began. The Statesman Journal ran a pro/con commentary with the headline “Drainage utility stirs up a storm.” In January 1988, a story appeared in Bend’s local paper that began, “The city of Salem’s attempt to tax Oregon’s most abundant commodity—rain—has run into a torrent of opposition from local businesses” (Towslee 1988). The article continues with comments from the realtor calling the scheme an unfair tax. “The people I have talked to think it’s silly to be charged for the rain that runs off rooftops and driveways” (ibid.).

By early 1988, enough signatures had been collected against the stormwater fee for it to be referred to the voters as a local ballot measure. Under the provisions of Salem’s city code, the City Council has the option of adopting or rejecting an initiative measure. If not adopted by the council, the measure must be submitted to voters at the next primary election. In the staff report to the council on February 8, 1988, the city manager noted, “One of the problems with this new utility has been a misunderstanding of its purpose and its true cost. The euphemistic name that has been placed on this revenue source has certainly not lent credibility to its implementation” (City of Salem 1988a).

The city manager recommended that the City Council adopt the initiative measure, thereby repealing the nascent stormwater utility, with an effective date of April 30. On February 16, the council adopted the initiative measure and on March 14, 1988, passed Ordinance Number 27-88, with a retroactive effective date of March 1, 1988. One of the reasons for the retroactive approach was given by the director of finance: “It would satisfy those citizens who feel that the effective date of the repeal of the [storm drain utility] should not have been delayed” (City of Salem 1988b).

As a consequence of the failed utility, Salem’s stormwater programs would be funded by the city’s wastewater ratepayers for the next two decades. For most wastewater customers, their sewer base is determined each year based on how much drinking water is consumed during the “wet season,” which for rate-setting purposes officially encompasses bills received in November through February. The assumption, quite valid in the mid-Willamette valley, is that very little, if any landscaping irrigation takes place during this period and any potable water coming into the property from the metered water service lines leaves through the unmetered wastewater lines. The problem with this approach from a stormwater perspective, however, is that there is no relationship between drinking water used in the winter and a property’s impacts on a municipal stormwater system. Despite the absence of a link between wastewater rates and stormwater services, this arrangement has never been challenged in Salem. In part, this is because the proportion of stormwater funding drawn from wastewater revenue remained relatively small during the early years following the 1988 defeat of the proposed stormwater utility.

However, not long after Salem’s abortive attempt to establish a stormwater fee, the cost of the city’s stormwater program began climbing with emerging state and federal regulations. In 1990, the US EPA codified rules for implementing the federal Clean Water Act’s National Pollutant Discharge Elimination System (NPDES) stormwater permit program. Salem received its first stormwater permit under the NPDES program in December 1997 and its second permit in March 2004. With each successive permit, the mandated regulatory, programmatic, and financial requirements expanded, and the cost of Salem’s stormwater program correspondingly increased.

Re-engaging the Rain Tax. In late 2009, it was determined by Public Works that, after a 20-year hiatus, the time was ripe to try again to implement a stormwater utility. This decision, which had been building for several years, was based on several factors:

- In fiscal year 2009–2010, approximately $0.23 of every dollar collected from wastewater ratepayers went to Salem’s stormwater programs. With more and more wastewater revenue funding stormwater services, the existing fee structure was becoming increasingly unfair to our wastewater ratepayers.

- With a new NPDES stormwater permit anticipated in late 2010, coupled with the recent completion of a series of major wastewater capital projects, it was anticipated that the revenue needs for stormwater were likely to start increasing at a higher rate than those for wastewater.

- Creating a stormwater utility was not nearly as novel an idea in 2010 as it was in 1983 (or in 1987–1988). If the City Council had approved the stormwater utility when it was first proposed in 1983, our city would have been among of the first in the state to have done so, joining Portland, Corvallis, Medford, and Eugene. In 2010, no fewer than 40 cities in Oregon were funding their stormwater programs with a stormwater fee.

How Salem Did It: The Starting Block

In preparation for what we knew would be a concerted public relations effort, Public Works began with a very simplistic stormwater rate construct based simply on the relationship between impervious surface and the stormwater program costs, using the most basic definition of impervious surface. Buildings, rooftops, paved surfaces, and unpaved surface areas subject to vehicular traffic, no matter where or how they drained, were all included in the impervious area determination. Trees, lawns, and other vegetated surfaces, no matter where or how they drained, were not considered impervious. In essence, gray was in; green was out. Using statistical sampling, the average impervious surface area of a single-family home in Salem was determined to be approximately 3,000 square feet. This value was set as one Equivalent Dwelling Unit, or EDU. The impervious surface area of every property was then converted to EDUs using our geographic information system (GIS), automated computer analysis, and hand-drawn lines on aerial images. Finally, the total number of EDUs was divided into the annual budget of Salem’s stormwater program to establish a dollar cost per EDU. We initially estimated that there were between 85,000 and 105,000 total EDUs in Salem. Based on these two values and assuming a $10 million annual stormwater program budget, the annual stormwater fee was calculated to range between approximately $95 and $118 per EDU or roughly $8 to $10 per month.

In 1983, the originally proposed stormwater rate per EDU of $3.60 per month would have made Salem’s rate the highest in Oregon, $0.65 more than second highest in Medford and four times that of Portland. The 1987 proposal of $0.75 would have made ours the lowest. In 2010, we believed the proposed rate, when compared to other cities in our region, should be neither too high nor too low for a municipality of the size and with the regulatory responsibilities of Salem. The table on the next page shows how Salem’s initially proposed stormwater rate per EDU compared to the residential rates of stormwater utilities in other cities in our region, using rate values effective as of July 2010.

How Salem Did It: The Run

From the time we officially, publicly unveiled the proposed stormwater utility at a January 2010 City Council work session until the final vote was taken in December 2010, we followed a course of action that had two key features: engage the public and ensure the feedback counted.

Getting the Word Out. Still mindful, even after20 years, of how the city’s last attempt to create a stormwater utility ended and resolved not to fail again, we took to heart what we believed to be the primary lesson learned:

Do not surprise your customers.

Standard practice is to develop a handy fact sheet, decide what questions were likely to be asked frequently and then write the answers in an FAQ document, update websites with helpful information and useful links, and distribute informative reports for our customers and elected officials. We did all that. We also developed a standard presentation that ensured consistent and cohesive information would be provided at public meetings regardless of the staff member presenting. And we established two key message points:

- Stormwater rates were being decoupled from wastewater rates. This is not a new fee, per se. We are simply separating two unique fees that are currently combined.

- We were not raising new revenue. If the proposed stormwater utility is not approved by the City Council, we will still have a $10 million stormwater program; it will just be paid for (as it is now) by our wastewater customers. (See the figure below.)

Most importantly—and this is where we understood that the previous attempts had fallen short—we chose to go out into the community with an ambitious list of target audiences, specifically seeking to talk to customers who would be most affected by a new stormwater utility. These customers would be relatively small water users (hence, they would currently have low wastewater bills), but would own large swaths of impervious surface (meaning they would end up paying a hefty stormwater fee).

It is one thing to go to 19 neighborhood association meetings and tell an audience of predominantly single-family residential homeowners that their overall rates will go down by several dollars per month as a result of implementing a stormwater utility. It is quite another matter altogether to share the idea of forming a stormwater utility with a local car dealer (an increase of $460 per month), a neighborhood grocery store (an increase of $900 per month), the school district (an increase of $25,000 per month, or nearly double), or the pastor of a large church (an increase of $1,350 per month, or 840%).

Between January and December 2010, staff from Public Works ventured repeatedly into the community to discuss the proposed stormwater utility. In addition to the 19 neighborhood association meetings, records show that we met with 13 individual businesses, seven citizen boards and committees, six government agencies, six community groups, and five trade organizations. We met eight times with the Water/Wastewater Task Force. The task force meetings were open to the public, and we almost always had interested parties attend. Additionally, we held two City Council work sessions that were well attended by the public. There were also uncounted numbers of one-on-one meetings and phone calls with interested customers, as well as several interviews with the Statesman Journal.

Three entities proved critical to the success of our endeavor. The first was the Water/Wastewater Task Force, which met periodically to review policy options and make recommendations to the Public Works director. This group was particularly important as the structure of the stormwater fee deviated more and more from the initial (and very simple) dollar-per-area-of-impervious-surface rate model. The task force members proved their value time and again when policy choices had to be made that benefited one class or type of customer to the detriment of another, in large measure because multiple interests were represented by members of the task force. It was specifically because of feedback received from the Water/Wastewater Task Force, for example, that the single-family residential rate, originally a single ESU for all homeowners, was modified to be a three-tiered fee structure to account for the very large and the very small impervious surface areas of some houses in Salem.

The second key group was City Council, which held two lively work sessions during which many issues and options were presented and discussed. Before the final vote in December 2009, the council conducted a public hearing that spanned two council meetings, one in October and the other in December. The mayor and three of our eight councilors were also members of the Water/Wastewater Task Force, which afforded them the opportunity to directly participate in the detailed discussions and policy recommendations from a front-row vantage point.

The value of having well-educated elected officials cannot be overestimated; these are the individuals who must be able to discern the merits of various comments and opinions made during public input and internal debates. There are many things to both like and dislike about forming a stormwater utility and one of our primary objectives was to make sure our councilors understood the issues, the options, and the reasoning behind our recommendations. In our view, for example, a speaker decrying the moral impropriety of “taxing” someone just because it rains on his or her roof and driveway was not a decision-making hinge-point. In contrast, the adverse consequences of higher utility bills to struggling commercial businesses and nonprofit organizations during a major recession were, in our view, real issues that needed to be considered. We were diligent in presenting to our councilors how various proposals were likely to impact different types and classes of potential stormwater ratepayers, both the positive and the negative, and we gave relative dollar values whenever we could.

The third group that was absolutely essential in getting the stormwater utility approved, despite the fact that Salem was in the worst economic downturn in decades, was the Salem Area Chamber of Commerce. Salem Public Works and the Salem Area Chamber of Commerce have had a good working relationship for many years. The two had worked closely together on a $100 million bond measure to improve public streets and other transportation infrastructure, which was approved by voters in November 2008. Getting the chamber’s support for a new stormwater utility fee that would significantly increase the operating costs to many of its members would be a challenge. We first presented the proposed stormwater utility to the chamber in early March 2010—we made sure that they were one of the first major audiences to hear about the proposal—and we met multiple times with senior officers and members of the chamber during the weeks and days leading up to the final vote by the council, discussing in more detail the evolving utility proposal and the potential implications to their members.

Making Sure the Feedback Counted. Salem Public Works embarked on a yearlong outreach effort that was much more than public education . . . it was public engagement. It is fair to say that the stormwater utility that was finally approved by the City Council in December 2010 was strikingly different from the one we first proposed to our councilors nearly 12 months earlier at the January workshop. The changes made were almost entirely the result of feedback received during interactions with our customers, most particularly the Chamber of Commerce, but also because of input from councilors and members of the Water/Wastewater Task Force. A few of the more significant changes:

- Implementation of the new stormwater fee was delayed from January 2011 until January 2013;

- The new stormwater fee would be phased in over a four-year period; and

- The stormwater rate structure would have two components: a fee determined by the property’s impervious surface area (the EDU-based fee) and a stormwater base fee that would be the same for all stormwater ratepayers regardless of the amount of impervious surface.

Our objective was to hold to the core principles of fairness and understandability, but otherwise exercise every bit of utility-making discretion needed:

- to gain the support of our customers (or, if not support, at least informed dissent);

- to get the endorsement of the Chamber of Commerce (or, if not endorsement, at least not outright opposition); and

- to obtain full support from City Council (or, if not full support, at least five votes).

Several of us believed that if we failed this time, it would quite likely be another 20 years before our successors would consider trying it again.

Probably nowhere did we exercise more discretion in crafting what became our eventual stormwater rate structure than when we added a per-account base fee to the EDU-based fee. The explicit purpose of establishing this base fee was to mitigate the cost impacts to our non-residential customers. By spreading a portion of the stormwater program costs equally among all 39,000 stormwater customers through a flat, per-account charge, the remaining EDU-based fee would decrease. This would clearly benefit the approximately 2,200 commercial customers, who would still be significantly impacted by the stormwater fee. However, it also meant that the anticipated rate reduction that would otherwise be seen by our 37,000 residential customers would be less.

Working with our consultant team, the Water/Wastewater Task Force, the Chamber of Commerce, and many others, we identified certain stormwater programmatic activities that could be considered generally independent of a property’s impervious surface. Street sweeping, billing account/maintenance, bad debt collection, and our 24-hour Public Works Dispatch Center were obvious choices. Less obvious, but nevertheless incorporated into the base charge—and done much to the consternation of more than one stormwater professional—we also estimated a value related to the total amount of impervious surface of public streets and incorporated that, too, into the base fee.

How Salem Did It: The Finish Line

At the public hearing on October 25, 2010, testimony was given by three individuals and seven organizations regarding the proposed stormwater utility. One individual was neutral on the subject and a representative from one of our watershed councils came to speak in support; however, the Chamber of Commerce, the Salem-Keizer School District, and the Salem Association of Realtors all spoke in opposition. Their testimony was followed by much questioning of staff by the councilors as well as discussions among themselves on the council floor. At one point during the discussions, a motion was made by one councilor (who later voted against the measure) for Public Works to wait on the proposal and not return to the council until January 2012; this motion was defeated and deliberations continued. The council meeting ran into overtime, and the members voted to continue the public hearing on December 6, 2010. The council also directed Public Works staff to meet with representatives of the Chamber of Commerce, Salem Association of Realtors, and other interested parties before returning in December. Following the October meeting, we did, indeed, meet several times with key stakeholders, primarily the Chamber of Commerce, and continued to adjust our recommendation.

At the public hearing on Monday, December 6, 2010, a revised recommendation was provided by Public Works to the City Council (City of Salem 2010), and additional testimony was received from five more individuals (one in favor, two opposed, two neutral). Three organizations also spoke to the council, all representing local churches and all in opposition. Representatives from the Chamber of Commerce were in the council chambers to observe the proceedings, but they chose not to speak. After the public hearing was closed and following more discussion, Salem City Council voted on the Public Works recommendation to create a stormwater utility.

It passed 6-2, with one abstention.

Defeating the “Rain Tax.” The next Sunday’s Statesman Journal contained an editorial titled “Creating Stormwater Utility was Right Move” (Statesman Journal 2010). It began, “Rain is free, but getting rid of it is expensive. Last week, the Salem City Council acted responsibly by voting to gradually make those costs more equitable. It was a good decision and one that reflects the tough times that local businesses still face.”

More than simply summarizing the details of the City Council-approved utility, the editorial staff of the Statesman Journal used most of the editorial expressing a positive viewpoint of the process itself. Some excerpts:

Overall, taxpayers are the winner because, in many ways, the city’s handling of this issue has exemplified local government at its best:

Salem’s public works staff spent a year discussing the proposal with property owners, neighborhood associations, business groups, and others. Staff members

conducted more than 50 meetings, which were noteworthy for their civil give-and-take.The council had a robust debate on the latest proposal Monday instead of simply rubber stamping a staff recommendation. Extensive debate is essential to a

healthy democracy that respects citizen input.The city adopted a plan that fits Salem’s needs instead of simply copying what other cities have done. City staff made numerous changes throughout the year to

address property owners’ concerns, especially those of large businesses and non-profits. The final plan spreads the basic charge more evenly, lessening some of

the impact on organizations with big parking lots.For a community that prides itself on its environment, the new stormwater utility makes sense.

For a community that needs to rebuild its economy, the city’s thoughtful and even-handed approach sends a positive signal to businesses.

The words “rain tax” did not appear anywhere in the Statesman Journal following the 2010 council vote.

The term, apparently, had dried up.

How Salem Did It: Figuring Out How to Take a Victory Lap

Initially, several members of our staff were disappointed that the City Council’s vote included a two-year delay before initially implementing the stormwater fee. After all, when an earlier council approved the first utility in June 1987, the new fee was effective three months later. However, it soon became apparent that with greatly improved computing power, extensively populated databases, newly updated GIS layers, and the ability to issue electronically generated billing statements, we would need significantly more time than our predecessors did before we could issue the first utility bills containing the new stormwater fee.

Looking back, the delay was a good thing.

The first bills containing the new stormwater fee were sent to customers in February 2013, reflecting January’s new charges. Between December 2010 and January 2013, there was a tremendous amount of behind-the-scenes quality staff work completed. This included linking our GIS data with our Hansen customer billing data, revising impervious surface determinations, and developing customer service support protocols. Adding a layer of complexity to the process, Public Works completed a new cost of service analysis for water and wastewater in August 2012, the City Council approved rate increases in November 2012, and Public Works completely revamped the form and format of our billing statements.

Again, there was a significant amount of public outreach conducted prior to the new bills being sent to our customers. This included focus groups, community meetings, informational pamphlets and videos (English and Spanish), and mass mailings. Stormwater fee estimates, along with maps showing our delineation of impervious surfaces, were mailed to each of our 2,200 non-single-family-residential customers.

Lessons Learned

Salem’s successful endeavor to create a stormwater utility in the midst of a severe economic downturn did not generate new lessons learned as much as it affirmed principles of local government that are already well known. Consider these three:

Communications are Essential. The advantage being clear in the message is that no matter the final vote, the outcome was more likely to be based on a clear understanding of the relative merits of the proposal and not on spun hyperbole. More than simply conveying a message, our communications strategy was to provide opportunities to exchange information and ideas. We made it clear to our various audiences that we wanted feedback and that what we heard mattered. Additionally, we were straightforward, to the point of being blunt, in our analysis. In the information we provided in our presentations to the City Council, in our printed material, and at every public forum, we made sure to address both the advantages and disadvantages of establishing a stormwater utility. We recognized that there would be significant cost implications and we gave cost estimates where we could. We acknowledged the risks and consequences, worked to reduce the impacts, and did not overhype the positive aspects of the utility. We gained some measure of credibility over time, because as we continued to meet with our customers we could point to how the proposal was evolving because of feedback we received. That the approved version of Salem’s stormwater utility had changed markedly from the original proposal is evidence that what others said really made a difference.

It is Tempting to Focus on Technical Details and Forget to Address New Policies. Even as our technical staff members were reconciling and integrating geographic information, customer data, and billing rates, a surprising number of pesky policy voids began emerging that needed resolution. For example:

Do we bill properties with vacant buildings?

Answer: Yes, provided they have an active water or sewer account.

Should we charge a stormwater fee even if a runoff never leaves the property?

Answer: Yes. It was a clear policy decision to keep the rate methodology very basic. In essence, when determining the amount of impervious surface for a ratepayer, gray was in and green was out, regardless of where pavement may be draining or the amount of runoff a turf area was actually generating. We readily acknowledge that accuracy can be compromised by simplicity, and accusations of unfairness continue to be raised from time to time by certain stormwater ratepayers.

Should “stormwater-only” accounts be set up for properties that do not use city services for water and wastewater?

Answer: Yes. Admittedly, we totally missed the stormwater-only account issue at first. In fact, we became aware of the 461 properties (394 residential, 67 commercial) served by wells and onsite septic systems so late that we delayed issuing stormwater bills to these customers for six months.

It is Relationships That Really Matter. In reviewing the track history of stormwater utility formation across the country, I am struck by the degree to which working relationships among key factions plays a role. In some locales, utilities failed because relationships were not strong enough to withstand significant (and legitimate) differences of opinion. As a result, groups splintered and walls were erected, making it extremely difficult to understand and acknowledge the others’ motivations and concerns. Consider, for example, that a month before Salem’s City Council voted in favor of the stormwater utility, voters in Baldwin County, AL, voted to reject a stormwater fee by a 7–1 margin (Baggett 2010). A casual read of the mood leading up to the vote reveals a highly divided and non-compromising atmosphere that frustrated communications (Henderson 2010). In our case, and in contrast, we had worked over many years to develop positive relationships between city staff and City Council and between Public Works and our customers. These relationships did not, and still do not, translate into carte blanche approval of any specific group’s proposals. The relationships do, however, establish an environment in which there is an ability to disagree, a willingness to understand the points of view of others, an interest in identifying areas of common ground, and a professional respect to engage in a robust discussion of ideas and alternatives. Our councilors, members of the Chamber of Commerce, our customers, and Public Works staff have all worked closely together on past projects, and we all knew that we would be working together in the future on new ventures. One of the goals in our effort to bring forward a stormwater utility in Salem was to do so in a manner that retained the existing and positive working relationships, no matter the outcome.

In this, too, we were successful.

References

Baggett, C. 2010. “Baldwin County Stormwater Initiative Far from Dead after Voters Reject Local Amendment One.” Press-Register, November 9, 2010, Baldwin County, AL.

City of Salem. 1987. A Proposed Storm Drainage Utility. Staff report from director of Public Works to mayor and City Council for council meeting of April 6, 1987, and public hearing of June 15, 1987. Print.

City of Salem. 1988a. Storm Drainage Service Charge. Staff report from city manager to mayor and City Council for council meeting of February 8, 1988. Print

City of Salem. 1988b. Storm Drain Utility. Staff report from director of Finance to mayor and City Council for council meeting of March 7, 1988. Print

City of Salem. 2010. Additional Information Regarding the Creation of a Stormwater Utility. Staff report from director of Public Works to mayor and City Council for council meeting of December 6, 2010, Agenda Item No. 8(b).

Henderson, R. 2010. “Baldwin County Stormwater Amendment Faces Critics at Public Forum,” Press-Register, November 9, 2010, Baldwin County, AL, October 14, 2010.

Statesman Journal. 1983a. Storm Drain Utility Charge Draws Protest.” Statesman Journal, September 27, 1983. Salem, OR, p. 1B, 3B. Microfiche.

Statesman Journal. 1983b. “Community Can’t Do It All.” Statesman Journal, October 3, 1983. Salem, OR, p. 6A. Microfiche.

Statesman Journal. 1987a. “Meetings.” Statesman Journal, June 8, 1987, Salem, OR, p. 2C. Microfiche.

Statesman Journal. 1987b. “Renters Say They’re Getting Soaked by City Rain Tax.” Statesman Journal, June 9, 1987, Salem, OR, p. 1C, 3C. Microfiche.

Statesman Journal. 1987c. “Council OKs Rainwater Tax.” Statesman Journal, June 16, 1987, Salem, OR, p. 1C. Microfiche.

Statesman Journal. 2010. “Creating Stormwater Utility Was Right Move.” Statesman Journal, December 12, 2010, Salem, OR, sec. 10C. Print.

Towslee, T. 1988. “‘Rain Tax’ up against Opposition in Salem.” The Bulletin, January 26, 1988, Bend, OR, p. A3.

Robert D. Chandler, Ph.D., P.E., is the assistant public works director for Salem.