Settling Column Method

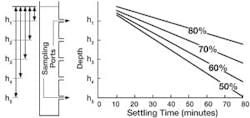

The shortcomings of using Stokes Law and related equations are potentially overcome by measuring the settling velocity distribution directly using a settling column. The columns have a diameter of 6 to 12 inches (15 to 30 centimeters) and a height of 3 to 6 feet (1.5 to 3 meters). The settling velocity is determined by placing a stormwater sample in the column. The concentration of particles is determined by withdrawing samples at specified times and points, typically 1-foot intervals, along the column. A plot is made of removal efficiency, which is the observed concentration in each sample from the column divided by the original concentration times 100, versus depth, as illustrated in Figure 3. Note that the lines in Figure 3 are straight, indicating a discrete suspension. Clearly the settling velocity of sand cannot be measured as it immediately drops to the bottom of the column. But this does not matter, given the ease with which sand is removed. What matters is the settling velocity of silts and clays.

If the suspension is flocculent, the lines curve downward. This suggests that with discrete settling, the settling rate is independent of the depth of the basin, whereas with flocculent settling, the settling rate is dependent on depth and therefore the hydraulic residence time. Figure 4 presents a summation of data of settling velocity distributions observed with stormwater. Note the tremendous variability. The rates in Figure 4 are for silts and clays.

There are potential biases with column tests. Length and temperature of sample storage affects settling velocity. Median settling velocity increased from 0.036 to 0.08 feet per minute (0.018 to 0.04 centimeter per second) between same-day and next-day testing with the stormwater stored at room temperature. Sample refrigeration further increases settling velocities. The effect is greatest with fine particles. This is consistent with observations regarding the effect of temperature on clay flocculation. Although absence of turbulence in the column allows clays to settle, it delays flocculation. Thus, absence of mild turbulence in the column as exists in stormwater basins may understate the settling rate of clay. Other devices may better mimic stormwater settling.

Settling With Intermittent Flows

Stormwater flow is intermittent. Depending on the type a basin, there are one or two settling processes. One process occurs during each storm, called dynamic settling. The second process occurs between successive storms and is called quiescent settling. Stormwater treatment systems that retain water between storms have both dynamic and quiescent settling. Examples are wet ponds, wet vaults, and constructed wetlands. Stormwater treatment systems that are dry between storms experience only the dynamic settling process. Examples are grass swales, strips, fine-media filters, and extended detention ponds.

The manner of settling is not the same with each settling process. Furthermore, the relevant design parameter that affects the efficiency of each process differs, giving rise to a potential conflict for those systems as to design with both processes.

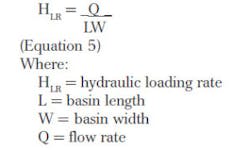

Dynamic Settling. With dynamic settling of discrete solids, the sole determinant of removal efficiency is the hydraulic loading rate (HLR). The HLR is the rate of flow into the treatment system divided by the surface area of the wet basin. The HLR has the units of ft3/ft2/day (m3/m2/day).

The common reason given for how vortex separation works in stormwater vaults is that the swirling motion (vortex) results in a longer flow path for the particle and in turn detention time: increased detention time for the particle, not the water. However, in the context of gravity separation, as opposed to vortex separation, this view is incorrect, as the velocity of the entering water in a vortex separator is too low. Vortex separators are more aptly described as swirl concentrators. Hence, the relevant design criterion is the hydraulic loading rate, the principles of which were first established in 1904, and shown in Equation 5.

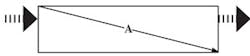

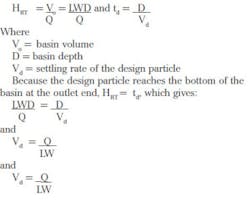

Note that Equation 5 does not contain the parameters of volume, depth or hydraulic residence time (HRT). With discrete settling these are not relevant factors in determining efficiency. Derivation of Equation 5 with the help of Figure 5 demonstrates this point.

The fraction of particles removed is a function of HRT/td where td is the time required for the particle of interest, or design particle, to reach the bottom of the basin at the outlet end (line A in Figure 5). All particles with settling velocities equal to or greater than the settling rate of the design particle (Vd) are captured. Some of the particles with lower settling velocities also are removed because as the water enters, the solids distribute across the vertical cross-section of the basin at the inlet. HRT and td are defined by:

Hence, the design HLR is the settling velocity of the target particle to be captured, Vd. The relationship is recognized when realizing the units for the HLR are ft3/ft2/day, the same for settling velocity of feet per day. This analysis indicates that two basins with the same volume, but different depths, have different removal efficiencies if both have the same hydraulic efficiency. The basin with the shallower depth and therefore greater surface area has the greater removal efficiency. Ignoring the potential for resuspension of settled sediments, a very shallow flat basin represents the optimal condition. The relationship between HLR and settling of TSS solids has been established.