The promulgation of trash total maximum daily loads (TMDLs) and associated requirements in municipal stormwater permits have instituted the need to characterize anthropogenic trash on land and water to support trash-related management decisions. Trash is widely recognized as a serious water-quality concern. Trash in the Los Angeles River has been of concern to many Los Angelenos over the years. The nonprofit Friends of Los Angeles River (FoLAR) has been holding The Great Los Angeles River CleanUp since 1990 and has characterized the trash found during some of the events. The city of Los Angeles, in 2012 and 2013, conducted a first-of-its-kind land characterization study of trash upstream from the receiving waters at five different land-use areas. Although not required for compliance with the various Los Angeles area trash TMDLs, these studies have provided insight into the composition and quantity of trash in water and land. The information from these studies will help agencies identify sources and potential methods of transport, and may lead to source control decisions, such as plastic bag or polystyrene bans, to most effectively reduce the amount of anthropogenic trash. This article describes the approach and results of the city of Los Angeles study and compares it with FoLAR results as described in FoLAR’s 2011 report, “A Trash Biography.” The assessment has shown that a disparity does exist in the character of trash in land compared to water.

Background

In March 22, 1999, USEPA and USEPA Region 9 settled a lawsuit (Heal the Bay v. Browner) through a consent decree requiring the development of numerous TMDLs for the Los Angeles area by 2012. EPA delegated the responsibility to implement these provisions of the Clean Water Act to the state of California, specifically to the Los Angeles Regional Water Quality Control Board (LARWQCB). The consent decree established a schedule for the development of certain TMDLs over the 13-year period.

Trash is widely recognized as a serious water-quality concern in California, impacting creeks, shorelines, rivers, and lakes. The LARWQCB further identified trash in urban runoff that is conveyed through the storm drain system as a primary source of pollution reaching the receiving waters. When trash is discarded on land, pollutants such as bacteria in animal droppings, household wastes, and toxic wastes are contained in or become entrained in paper, plastic, polystyrene, cans, and other debris, which are transported by rainstorms into gutters, storm drains, and eventually into waterways, lakes, and the ocean. Street and storm drain trash studies have been conducted in various California regions, including one conducted by the city of Los Angeles. These studies have provided insight into the composition and quantity of trash that flows from urban streets into the storm drain system and out to adjacent waters. The LARWQCB identified many beneficial uses being impaired due to trash in these water bodies. Aquatic and marine life can be threatened from ingestion, entanglement, and habitat degradation from trash. Trash can jeopardize public health and safety and poses a hindrance to recreational, navigational, and commercial activities.

Trash Studies

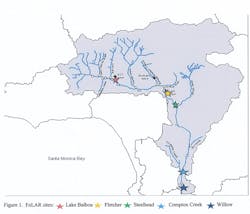

Friends of Los Angeles River Studies. FoLAR is a 501(c) 3 non-profit organization founded in 1986, whose mission is to “protect and restore the natural and historic heritage of the Los Angeles River and its riparian habitat through inclusive planning, education, and wise stewardship.” FoLAR has been holding The Great Los Angeles River CleanUp since 1990, in which thousands of volunteers have participated and thousands of pounds of trash have been removed. For several of the events, FoLAR has also characterized the trash found in the waterways to bring attention to the most prevalent trash types impairing this waterway, which runs for 51 miles—from the suburbs of the San Fernando Valley to the ocean in Long Beach. The Los Angeles River flows through 14 cities and countless neighborhoods. FoLAR began sorting trash in 2004 and conducted additional trash sorts in 2005, 2009, 2010, and 2011 at five locations (Figure 1).

Trash was collected along the riverbanks only, and randomly selected bags of trash were pulled from each site and sorted. Trash flowing in the water down the river was not collected. The selected locations and year in which the sorting was conducted varied, most likely depending on available volunteer resources. In addition, based on FoLAR’s “A Trash Biography” report, it is difficult to determine the quality assurance/quality control, and study inconsistencies may occur. For example, volume was recorded but weight was not recorded in one collection year at the same location, and conversely, weight was recorded but volume was not recorded in the subsequent year. Sites where trash sorting occurred and the year(s) in which they took place are noted in Table 1.

The collected trash was sorted into 15 categories:

- Food service packaging (clamshells, cups, etc.)

- Snack and candy packaging

- Bottles and cans (California Redemption Value or “CRV” beverage containers)

- Non-CRV containers (other beverage containers)

- Molded plastic (non-beverage containers)

- Metal (non-beverage containers)

- Glass (non-beverage containers)

- Cigarette butts

- Polystyrene (Styrofoam, etc.)

- Paper bags, newspapers, etc.

- Plastic film, non-grocery bags

- Plastic film, single-use grocery bags

- Plastic film, tarps

- Clothes and fabric

- Other

Between 10% and 20% of the total number of trash bags were randomly selected and pulled for sorting. The number depended upon the total amount of trash collected and number of volunteers available to help sort the trash. FoLAR sorted and placed each category of trash into other trash bags of uniform size to roughly measure volume (in number of standardized trash bags). FoLAR also measured weight (in pounds), but concluded that volume is a better measurement of quantity. Pieces of metal, wet cloth, and plastic laden with wet sand would result in overestimates or underestimates of the true weight of the material.

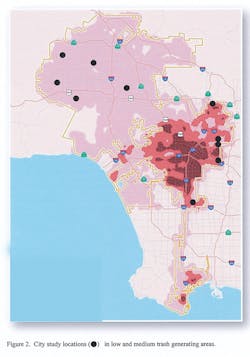

City of Los Angeles Trash Characterization Study. The city has had success in utilizing full- and partial-capture devices as well as institutional measures in meeting trash TMDL milestones. Since 2004, the city has conducted various studies to identify high-trash-generation areas, utilized mapping and field verification to identify land uses, and conducted studies of partial-trash-capture and deflection devices. Results of the study were evaluated and utilized to best implement the trash TMDL. The city has installed 38,000 catch basin screens, 10,000 catch basin inserts, six hydrodynamic separation devices, 13 netting systems, and 10 low-flow diversions to prevent trash from entering waterways, including the Los Angeles River. Although not required for compliance with the various Los Angeles-area trash TMDLs, the city also conducted a first-of-its-kind characterization study in 2012 and 2013, at 10 sites reflecting five different land-use areas, to determine types of trash being kept out of the catch basins (Figure 2). All previous characterization efforts had focused on types of trash that had been transported through the storm drain system to the receiving waterbody, and none had evaluated the types of trash being discarded on the watershed drainage area.

In 2012, the city, with consultant assistance from Black and Veatch, initiated a study that originally was to focus only on assessing the performance of institutional measures in low- and medium-trash-generating areas of the city, because the high-trash-generating areas had already been brought into compliance with the installation of full-capture systems. Although it was not required by the trash TMDL, the city decided to incorporate a characterization effort into the institutional study. Activities conducted in preparation for the study included devising a work plan, training field staff on identification, stating purpose, and identifying collection method. The field supervisor and project manager provided oversight and corrected actions in the field as necessary as a means of quality assurance and control.

The MS4 permit provides guidelines as to several methods that can be used to show compliance with the trash TMDL milestones; one of those requirements is a prescribed time period (June 22 through September 22) to determine a daily generation rate. In theory, this period would be representative of trash discharged or discarded by only human activity in the watershed and would not be influenced by climatological factors. Thus, the city study adopted an eight-week time period in July through August 2012 and June through August 2013.

After collecting the trash in 5-gallon containers marked for volume (gallons) in the street and in front of the street catch basins at the sites for purposes of the institutional study, crews then sorted trash and placed it into categories consistent with the categories established by FoLAR. The sorted trash was then weighed and the volume recorded (Figures 3 and 4). The city aims to utilize the characterization data in identifying and monitoring any trends in trash generation that possibly can be a focus effort for other source control bans.

Results

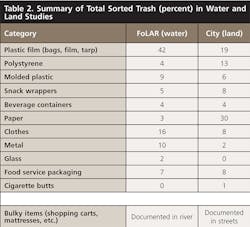

The data and results from FoLAR’s water-based and the city’s land-based characterization studies can be analyzed in various ways. Table 2 summarizes the total amount of trash collected and characterized from the two studies. For the city, the summary represents years 1 and 2 volumes (gallons) of trash collected from streets in medium- and low-trash-generating areas. For FoLAR, the table summarizes the results from the five riverbank sites where trash was collected and sorted.

The composition of trash collected on land by percent volume is dominated by paper (30%) and is much greater than that collected on riverbanks (3%). Polystyrene was also collected in greater volume on land (13%) than in the river (4%). Conversely, plastic film (42%) represented the greatest volume in the river compared to streets (19%), followed by clothes (16%) and metal (10%). Small, light items such as snack wrappers and food service packaging were found in almost equal percentages in the water and on the land. Large and bulky items were noted in both land and water (Figure 5).

Conclusion

Based on the evaluation of the FoLAR river cleanups and the city of Los Angeles study, the types of trash found in waterways compared to the types found in the watershed land areas are distinct. Size and density appear to be the main distinguishing characteristics, which influence the mode of transport into the water bodies.

each bag of unsorted trash.

The evaluation of the results from the two studies seems to confirm that deposition of trash into the waterways is not solely due to the storm drain system, but that other factors also exist that contribute to the impairment of the water body by trash. A comparison of the studies seems to indicate that air deposition of trash may be significant, because much of the discarded material found in the water is of light composition and easily influenced by wind. Items such as plastic film and snack wrappers are most likely transported by wind and/or improperly disposed of by visitors along the riverbank as nonpoint sources. It is interesting to note that paper is the top material discarded in the watershed area, but hardly any was collected at the river. A plausible reason for paper not being seen at the water body is that paper absorbs water and eventually sinks and therefore is collected by river cleanup volunteers. Moreover, the Los Angeles River, having serendipitously fostered the growth of the city from the onset, has also become central to and impacted by social issues, such as homelessness. A large homeless population calls the Los Angeles River home, which may account for the large volume of clothing and fabric found during river cleanups. Direct deposit into the river of bulky items such as shopping carts and mattresses indicates that illegal dumping is still taking place, because these would not fit into storm drain inlets (catch basins) found throughout the watershed.

Many of the items found in both characterization studies are similar; the majority are small (9 inches or less) and light weight (low density). This seems to indicate that storm runoff or urban dry-weather runoff is the mode of transportation for lightweight, small-size trash into catch basins, through the storm drain system, and eventually into the receiving water. Size is important to note, because storm drain inlet structures (catch basins) typically have a curb opening height of 9 inches and various widths depending on the capture design for flow. This size parameter helps us understand the type of trash that we see in the waterway that may have come from the storm drain system, as shown by the data collected in the waterway and the trash categories selected. The city’s study also documented various instances of improper disposal of bulky items on land, where, if they were not removed, would have resulted in their decomposition and possible entrance into the storm drain system.

Since 2006, the city has been installing trash BMPs and currently has thousands of catch basin screens and inserts, several netting devices, hydrodynamic capture devices, and low-flow diversions across the city to prevent trash from entering the storm drain system. Runoff transports floatables such as polystyrene and plastic film and paper along the gutter to the fronts of the catch basin screens, which are designed with 5-millimeter openings. Based on evaluation of the FoLAR and city study data sets, the catch basin screens appear to be effective in preventing small and large pieces of trash from entering the river. FoLAR’s study showed large, small, and heavyweight pieces of trash collected along riverbanks. It is more likely the large and dense pieces of trash were illegally or improperly disposed of, as they are not likely to have been transported through the storm drain system nor transported by wind. The smaller, lighter trash pieces were found almost equally on land and water, which indicates the catch basin screens prevent these small pieces from entering the storm drain system via stormwater runoff, but cannot prevent them from being wind-blown or improperly disposed into the water body.

The information obtained from the two studies can be used to help shape future compliance methods for trash TMDLs. These may include focused institutional efforts to target nonpoint sources such as parks and open space where large amounts of polystyrene and food and drink packaging were collected. There may be need to enhance enforcement for illegal dumping, and to focus education to target high-trash-generation areas such as alleyways. Finally, the information may assist in moving forward to the “next-generation” BMPs, legislative approaches.