The promulgation of trash total maximum daily loads (TMDLs) and associated requirements in municipal stormwater permits have instituted the need to characterize anthropogenic trash on land and water to support trash-related management decisions. Trash is widely recognized as a serious water-quality concern. Trash in the Los Angeles River has been of concern to many Los Angelenos over the years. The nonprofit Friends of Los Angeles River (FoLAR) has been holding The Great Los Angeles River CleanUp since 1990 and has characterized the trash found during some of the events. The city of Los Angeles, in 2012 and 2013, conducted a first-of-its-kind land characterization study of trash upstream from the receiving waters at five different land-use areas. Although not required for compliance with the various Los Angeles area trash TMDLs, these studies have provided insight into the composition and quantity of trash in water and land. The information from these studies will help agencies identify sources and potential methods of transport, and may lead to source control decisions, such as plastic bag or polystyrene bans, to most effectively reduce the amount of anthropogenic trash. This article describes the approach and results of the city of Los Angeles study and compares it with FoLAR results as described in FoLAR’s 2011 report, “A Trash Biography.” The assessment has shown that a disparity does exist in the character of trash in land compared to water.

Background

In March 22, 1999, USEPA and USEPA Region 9 settled a lawsuit (Heal the Bay v. Browner) through a consent decree requiring the development of numerous TMDLs for the Los Angeles area by 2012. EPA delegated the responsibility to implement these provisions of the Clean Water Act to the state of California, specifically to the Los Angeles Regional Water Quality Control Board (LARWQCB). The consent decree established a schedule for the development of certain TMDLs over the 13-year period.

Trash is widely recognized as a serious water-quality concern in California, impacting creeks, shorelines, rivers, and lakes. The LARWQCB further identified trash in urban runoff that is conveyed through the storm drain system as a primary source of pollution reaching the receiving waters. When trash is discarded on land, pollutants such as bacteria in animal droppings, household wastes, and toxic wastes are contained in or become entrained in paper, plastic, polystyrene, cans, and other debris, which are transported by rainstorms into gutters, storm drains, and eventually into waterways, lakes, and the ocean. Street and storm drain trash studies have been conducted in various California regions, including one conducted by the city of Los Angeles. These studies have provided insight into the composition and quantity of trash that flows from urban streets into the storm drain system and out to adjacent waters. The LARWQCB identified many beneficial uses being impaired due to trash in these water bodies. Aquatic and marine life can be threatened from ingestion, entanglement, and habitat degradation from trash. Trash can jeopardize public health and safety and poses a hindrance to recreational, navigational, and commercial activities.

Trash Studies

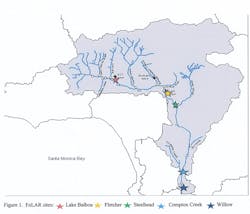

Friends of Los Angeles River Studies. FoLAR is a 501(c) 3 non-profit organization founded in 1986, whose mission is to “protect and restore the natural and historic heritage of the Los Angeles River and its riparian habitat through inclusive planning, education, and wise stewardship.” FoLAR has been holding The Great Los Angeles River CleanUp since 1990, in which thousands of volunteers have participated and thousands of pounds of trash have been removed. For several of the events, FoLAR has also characterized the trash found in the waterways to bring attention to the most prevalent trash types impairing this waterway, which runs for 51 miles—from the suburbs of the San Fernando Valley to the ocean in Long Beach. The Los Angeles River flows through 14 cities and countless neighborhoods. FoLAR began sorting trash in 2004 and conducted additional trash sorts in 2005, 2009, 2010, and 2011 at five locations (Figure 1).

Trash was collected along the riverbanks only, and randomly selected bags of trash were pulled from each site and sorted. Trash flowing in the water down the river was not collected. The selected locations and year in which the sorting was conducted varied, most likely depending on available volunteer resources. In addition, based on FoLAR’s “A Trash Biography” report, it is difficult to determine the quality assurance/quality control, and study inconsistencies may occur. For example, volume was recorded but weight was not recorded in one collection year at the same location, and conversely, weight was recorded but volume was not recorded in the subsequent year. Sites where trash sorting occurred and the year(s) in which they took place are noted in Table 1.

The collected trash was sorted into 15 categories:

- Food service packaging (clamshells, cups, etc.)

- Snack and candy packaging

- Bottles and cans (California Redemption Value or “CRV” beverage containers)

- Non-CRV containers (other beverage containers)

- Molded plastic (non-beverage containers)

- Metal (non-beverage containers)

- Glass (non-beverage containers)

- Cigarette butts

- Polystyrene (Styrofoam, etc.)

- Paper bags, newspapers, etc.

- Plastic film, non-grocery bags

- Plastic film, single-use grocery bags

- Plastic film, tarps

- Clothes and fabric

- Other