Fecal Indicator Bacteria Reduction in Urban Runoff

Editor’s note: This article first appeared in the September 2012 issue of Stormwater.

Pathogens are the top cause of stream impairments nationally, with over 10,500 stream segments identified as impaired as of 2012—typically due to elevated concentrations of fecal indicator bacteria (FIB) in waterbodies. Although strict numeric effluent limits for stormwater discharges are not typically required yet in most communities, the implementation phase of total maximum daily loads (TMDLs) may result in National Pollutant Discharge Elimination System (NPDES) stormwater discharge permit requirements to reduce FIB, including numeric effluent limits. Such requirements have been typically based on implementation of best management practices (BMPs).

However, increasingly there are cases where numeric effluent limits are being incorporated into permits. Therefore, it is important to have a good understanding of bacteria sources, effective treatment processes, and typical BMP performance. The International Stormwater BMP Database and associated BMP performance reports are a key source of information that can be used to develop realistic expectations of BMP performance with regard to FIB.

In 2010, the Water Environment Research Foundation (WERF), the Federal Highway Administration (FHWA), and the American Society of Civil Engineers’ (ASCE) Environmental and Water Resources Institute (EWRI) cosponsored a comprehensive stormwater BMP performance analysis technical paper series relying on data contained in the International Stormwater BMP Database. The BMP database is a long-term project that began in 1994 through the vision of members active in the Urban Water Resources Research Council of ASCE and the leadership of EPA. Funded for many years by EPA, the project is now supported by a coalition of partners including WERF, FHWA, EWRI, and the American Public Works Association (APWA). The technical reports can be downloaded here. This series, published in 2010 and 2011, includes papers for solids, bacteria, nutrients, metals, and volume reduction, with each paper summarizing the regulatory context of the constituent category, primary sources, fate and transport processes, removal mechanisms, and statistical summaries of BMP performance for data contained in the BMP database. Since then, nearly 100 new BMP performance studies have been added to the BMP database, resulting in over 500 BMP performance studies. As a result of this significant expansion of the database, statistical summaries for each constituent category were updated in a Pollutant Category Summary Statistical Addendum for TSS [total suspended solids], Bacteria, Nutrients, and Metals (Geosyntec and WWE 2012).

This article provides highlights of new BMP effectiveness data for FIB resulting from the 2012 BMP database analysis, along with additional interpretation of analysis results. Because these findings highlight the difficulties of reducing FIB to meet instream primary contact recreation criteria using passive treatment BMPs, several case studies of approaches being used in southern California to address FIB TMDLs are discussed. These case studies focus heavily on source controls, which are a fundamental component of FIB TMDLs.

Regulatory Background

Under the federal Clean Water Act, US EPA establishes Ambient Water Quality Criteria (AWQC) for bacteria to protect human health. Currently, EPA uses Escherichia coli (E. coli) and enterococcus as indicators of fecal contamination of receiving waters. These FIB are present in the intestines of warm-blooded animals and are easier to identify and enumerate in water-quality samples than the broad range of pathogens in human and animal feces. In December 2011, EPA released proposed updated Recreational Water Quality Criteria for public comment, with a final update to be issued in late 2012. Table 1 provides a summary of key components of the proposed updated criteria, including magnitude, duration, and allowed exceedance frequency components. (See EPA [2011] for more detailed information on the criteria.) Although the proposed update of the criteria includes a number of proposed changes, the primary contact geometric mean values are the same as those specified in the 1986 criteria.

Statistical Analysis

FIB data in the BMP database were statistically analyzed based upon the distributions of influent and effluent water quality for individual events by BMP category, thereby providing greater weight to those BMPs for which there are a larger number of data points reported. In other words, the performance analysis is “storm-weighted,” as opposed to “BMP weighted.”

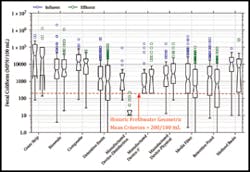

Side-by-side box plots for the various FIB and BMP types were generated using the influent and effluent concentrations from the studies. For each BMP category, the influent box plots are provided on the left and the effluent box plots are provided on the right. A key to the box plots is provided in Figure 1. In addition to the box plots, tables providing numbers of BMPs and storm events, geometric mean outflow concentrations, influent/effluent medians, and 25th and 75th percentiles are provided, along with 95% confidence intervals about the medians, computed using the Bias-Corrected and Accelerated (BCa) bootstrap method described by Efron and Tibishirani (1993). Comparison of the confidence intervals about the influent and effluent medians can be used to roughly identify statistically significant differences between the central tendencies of the data. Non-parametric hypothesis testing, including the Mann-Whitney rank sum test and the Wilcoxon signed-rank test were also conducted to assess significant differences at the 95% confidence level between influent and effluent medians. The Mann-Whitney rank sum test applies to independent data sets, whereas the Wilcoxon signed-rank test applies to paired data sets. For a detailed description of statistical methods used, data screening, and detailed statistical appendices for each BMP type-FIB type combination, see Geosyntec and WWE (2012).

BMP Database Analysis Results

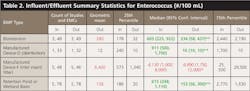

Figures 2 through 4 and Tables 2 through 4 summarize available FIB data in the BMP database. Geometric mean effluent values above relevant primary contact criteria are shown in red. (Statistical values presented in this paper are taken directly from Geosyntec and WWE [2012]. Color coding and types of statistics included in summary tables have been modified slightly for purposes of this article.) Median effluent concentrations, shown in bold green typeface, indicate that one or more hypothesis tests indicate statistically significant reductions in FIB. Median effluent concentrations, shown in italicized red typeface, indicate that one or more hypothesis tests indicate statistically significant increases in FIB. Values with no special color or font emphasis indicate that hypothesis testing did not indicate statistically significant differences between the influent and effluent concentrations. For FIB, confidence intervals for the median influent and effluent concentrations overlap for most BMP-FIB combinations, consistent with the highly variable nature of FIB sample results, which may span multiple orders of magnitude. (A notable exception is an active treatment manufactured device BMP providing disinfection.) When interpreting these tables, the number of studies per BMP category and number of storm events sampled are important considerations. For enterococcus, the retention pond and wetland basin categories were combined into a single category due to the small data set for this constituent and relatively similar unit treatment processes.

Findings from BMP Database Performance Analysis for FIB

Based on the performance data available to date in the BMP database, the following general observations can be made regarding stormwater BMP performance for FIB:

- As would be expected, the BMP database data sets show that FIB concentrations in urban runoff are characterized by high concentrations, which are often one to two (or more) orders of magnitude greater than primary contact recreational standards. Additionally, FIB concentrations in influent to and effluent from BMPs are highly variable, presenting challenges for data interpretation and statistical analysis (i.e., these are “noisy” data sets). The variability is also likely amplified because these data are primarily from analysis of single grab samples versus flow-weighted (averaged over a storm) samples.

- Despite the significant increase in numbers of studies in the BMP database, data sets for most BMP-FIB combinations remain limited. In some cases, characteristics of the data set constrain data interpretation. For example, the bioretention data set for E. coli is limited to three studies with unusually low median influent concentrations. These characteristics may partly explain lower level of confidence regarding whether statistically significant differences exist between influent and effluent medians, as well as limit understanding of effluent concentrations that may be achieved under higher (more typical) influent FIB concentrations. In other words, although the bioretention studies in the BMP database do not currently show statistically significant reductions in E. coli concentrations, they may, in fact, be shown to be effective when larger data sets become available and/or sites are added with higher influent concentrations. (Additionally, substantial volume reduction provided by well-designed bioretention facilities can provide FIB load reductions, even if effluent concentrations are not significantly reduced.)

- As would be expected, the one active treatment (disinfection) study analyzed demonstrated consistent reduction of enterococcus and fecal coliform to levels below primary contact recreation standards. Despite this performance, active treatment of stormwater is not a realistic solution at the watershed scale for most urban areas and may still not result in receiving waters attaining primary contact standards due to environmental factors downstream (e.g., animals) or regrowth.

- The majority of stormwater BMPs (relying on passive treatment) in the BMP database do not appear to be effective at reducing FIB effluent concentrations to primary contact stream standards. However, BMPs that reduce the frequency and magnitude of stormwater runoff volumes can help to reduce overall FIB loading to streams and potentially reduce the number exceedances of instream standards. Volume- and load-based analyses were beyond the scope of this article, but should be taken into consideration for practices such as bioretention, bioswales, grass strips, infiltration basins, and other practices providing volume reduction.

- The enterococcus data set is very limited, with five or fewer studies available for four BMP categories. The available data suggest that bioretention and retention pond/wetland basin BMP types are capable of reducing enterococcus concentrations, but not to primary contact recreation limits. The manufactured devices in the inlet insert/filter subcategory did not provide statistically significant reductions in FIB and appear to export FIB—possibly due to a bacteria-friendly environment created by the permanent wet pool, solids, and/or debris retained within the catch basin.

- The E. coli data set also remains limited, with five or fewer studies available for six BMP categories. Hypothesis testing showed statistically significant reductions in E. coli for retention (wet) ponds and detention ponds, but not to primary contact recreation standards. As previously noted, unusually low influent E. coli concentrations for bioretention data set limit conclusions that can be drawn from this particular data set regarding bioretention performance, even though effluent concentrations were below primary contact standards. The one green roof study in this data set had effluent concentrations below primary contact standards, but influent concentrations were also relatively low, as would be expected for an urban green roof. Wetland basin performance was inconclusive for this particular data set. Overall, the strongest performer in terms of concentrations for the E. coli data set was the retention pond category, which reduced relatively high E. coli concentrations to median concentrations slightly above the primary contact standard (although geometric mean concentrations were still approximately twice the standard).

- The fecal coliform data set contains more sample results than enterococcus and E. coli. Bioswales, detention basins, media filters, and retention ponds have 10 or more studies, with the remainder of the BMP categories having five or fewer studies. Geometric mean and median effluent concentrations for all categories analyzed were well above the historic primary contact limit of 200 cfu/100 mL; however, retention (wet) ponds and media filters provided statistically significant reductions in fecal coliform concentrations, based on paired and unpaired hypothesis tests. Paired hypothesis tests showed net export of fecal coliform from grass swales and inlet insert/filter manufactured devices and net reduction of fecal coliform for composite BMP systems (series of BMPs). Too few bioretention studies with fecal coliform data were available for inclusion in the fecal coliform analysis.

- The manufactured devices in the BMP database include a range of unit treatment processes and proprietary designs, requiring case-by-case evaluation of performance. When reviewing the manufactured device findings for the BMP database, be aware that the data set included in this analysis is limited and does not include all types of manufactured devices currently on the market. Nonetheless, when the available data are divided into these three general categories—physical processes (e.g., hydrodynamic devices), inlet inserts/filters, and disinfection—the only manufactured device subcategory with statistically significant reduction is disinfection. Although disinfection of stormwater (or baseflows discharging from storm sewers) may be appropriate in some limited circumstances, disinfection of numerous outfalls at a watershed scale is typically not a realistic strategy for meeting instream FIB criteria.

- See WWE and Geosyntec (2010) for additional information on bacteria sources, unit treatment processes, and research needs related to FIB and stormwater BMPs.

Implications and Strategies for TMDL Compliance: Southern California Case Studies

Because most of the typical BMPs from the BMP database do not consistently achieve recreational (“REC”) limits in treated effluent, MS4 bacteria TMDL implementation plans (also referred to as load reduction plans and waste load allocation attainment plans) often utilize other strategies to meet waste load allocations (WLAs), which are expressed numerically in terms of allowable exceedance days in many southern California bacteria TMDLs. During dry weather, these plans rely heavily on source control and nonstructural BMPs first, and structural BMPs, such as low flow diversions to sewer, second. Effective dry-weather nonstructural BMPs are those that address sources of human fecal contamination to the MS4, as well as sources of dry-weather urban runoff that mobilize other sources (e.g., catch basin sediments and stormdrain biofilms) and contribute to monitorable outfall discharges. Such nonstructural BMPs include:

- Enhanced commercial inspection (noting that food outlet dumpster leaks, grease trap leaks, commercial catch basins, and pavement washdown have been identified as potent sources through various source investigations);

- Water conservation programs (targeting residential over-irrigation through smart controller distribution, free home water-use audits, and potentially fines for causing runoff to storm drains);

- Homeless waste control programs (e.g., enhanced inspection/enforcement, outreach, additional public restrooms, and even programs where homeless themselves are paid to collect trash and wastes from encampment areas); and

- Identification and control of sewer inputs into the MS4 (noting that studies in Santa Barbara have found aging leaking sewer lines, where they run near and above storm drains, may have a hydraulic pathway for sewage to enter the MS4 drip by drip over miles of pipe).

Figure 3. Box plots of influent/effluent E. coli concentrations

Challenges to these nonstructural BMP approaches include a lack of robust data to quantify anticipated effectiveness, which is necessary to compare cost per load removed with structural treatment or diversion solutions, and which is required by regulators to demonstrate “reasonable assurance” that proposed strategies will comply with

TMDL WLAs.

During wet weather, implementation plans primarily rely on nonstructural BMPs that address human and anthropogenic non-human sources of bacteria that are located throughout the urban area, because wet weather runoff may mobilize any or all of these. These nonstructural BMPs include homeless waste control programs; enhanced pet waste control programs (education/outreach, mutt mitts, and ordinance enforcement); pre-storm-season catch basin cleaning (noting that sediments, trash, and decomposing organic matter all contribute to bacteria levels); and others. However, nonstructural BMPs are not expected to be able to reduce wet-weather MS4 bacteria loads to achieve REC limits, even when exceedances are allowed based on reference watershed conditions, as they are in several southern California bacteria TMDLs. Therefore, strategic implementation of structural BMPs is a key component of wet-weather plans. As noted above, few of the passive treatment BMPs alone, such as those from the BMP database, are able to consistently achieve REC limits; therefore wet-weather plans must recognize these risks and uncertainties, and also must lean more on runoff volume reduction strategies such as infiltration and capture/use BMPs. One exception is the use of subsurface flow wetlands, which have a higher unit cost and BMP area to drainage area ratio than most other traditional stormwater treatment BMPs. Subsurface flow wetlands have been less well studied for bacteria, but have been shown to achieve REC limits in treated effluent on a relatively consistent basis.

Many southern California MS4 bacteria TMDL implementation plans are required to show a quantitative nexus with the WLAs, to demonstrate “reasonable assurance” of meeting the WLAs. For nonstructural BMPs, this is difficult and highly uncertain given the general lack of bacteria performance monitoring data that are needed to estimate concentration or load reductions associated with each activity, or alternatively the load contribution from the specific source that each addresses. Water-quality benefits of nonstructural BMPs have been estimated through simplifying assumptions; source allocation data (e.g., relative contributions from humans, birds, and pets); and load-based spreadsheet calculations, although the uncertainty remains high. For structural wet-weather BMPs, southern California communities have used models to support this quantitative nexus. One such modeling tool was developed in Los Angeles in coordination with the City of Los Angeles, the County of Los Angeles, the prominent environmental organization Heal the Bay, the Los Angeles Regional Water Quality Control Board (LARWQCB), and the California State Water Resources Control Board. This model is the Structural BMP Prioritization and Analysis Tool (SBPAT). SBPAT links USEPA’s SWMM (for continuous hydrologic analysis) with a stochastic stormwater quality model based on Monte Carlo. SBPAT is publically available for download and has been used for the development of numerous TMDL implementation plans (and more general watershed-based water-quality plans) in Los Angeles, Ventura, Orange, and San Diego counties. SBPAT supports 1) the identification and prioritization of retrofit opportunities (as well as priority areas should retrofit opportunities not be available), and 2) the quantification of water-quality benefits and costs within the plans, while also capturing the variability in these benefits and costs so that decision makers can be informed of their compliance uncertainty to allow risk-based decisions. This is particularly crucial given that the cost of many of these urban plans in Los Angeles and San Diego are several hundred million dollars; therefore, investment cost versus regulatory compliance risk is a crucially important balance to be weighed.

In spite of numerous BMP and quantification options, in many cases, bacteria TMDL limits (which, in California, include primary contact REC single sample and geometric mean limits) are very difficult to meet. For example, reference streams and beaches that serve as the basis for southern California TMDL (allowable exceedance day-based) WLAs often themselves do not meet the TMDL WLAs. Other cases where WLAs have not been met include 1) streams and beaches in subwatersheds with >95% undeveloped open space, 2) streams and beaches during dry weather where 100% of flows are diverted to sewer or to UV disinfection treatment, and 3) streams and beaches where several million dollars have been invested in aggressive wet-weather controls. Therefore, site-specific criteria special studies are now being considered, and this is particularly timely given that USEPA’s draft REC criteria (discussed above) allow site-specific criteria, where appropriate.

One example approach to development of site-specific criteria is through a quantitative microbial risk assessment (QMRA); another is through a natural source exclusion (NSE). A QMRA is a calculation of illness risk based on measured pathogen concentrations (e.g., viruses) to allow for a comparison between site-specific illness rates and EPA’s tolerable rates. If local estimated illness rates are lower than EPA’s tolerable rates, then site-specific criteria may be justified. An example QMRA study is now being led by the Southern California Coastal Water Research Project (SCCWRP) in the Los Angeles region under LARWQCB, EPA Region 9, and USEPA oversight, and this may set the precedent for how such studies may be conducted in the future. For an NSE, if anthropogenic sources are controlled (as demonstrated through source tracking) and risks are low, then site-specific criteria may be set based on existing water quality. Several southern California beaches are now applying for NSEs; however, none has yet been granted as of June 2012. Such studies are essential, given the significant number of dry-weather MS4 disinfection projects that have been effective at the point of discharge, only to have rebounds in FIB shortly downstream.

Conclusion

In summary, the BMP database is an evolving source of BMP performance information for FIB that can be used to develop estimates of structural BMP performance and support development of tools and models to assess potential TMDL compliance options for FIB TMDLs. To date, findings from the BMP database indicate that it is unlikely that typical structural stormwater BMPs relying on passive treatment can consistently attain primary contact effluent concentration limits for FIB. BMPs that help to reduce the frequency and volume of stormwater discharges can help to reduce FIB loading to streams. As a result, communities working toward TMDL compliance will likely find it necessary to implement multiple strategies, including aggressive and comprehensive nonstructural controls to target high-priority sources and costly structural BMP retrofits (including implementation at multiple scales, such as large regional projects and smaller LID-type distributed projects). Even with these efforts, it is not clear whether numeric wasteload allocation attainment will be feasible in urban areas; therefore, special studies to both support implementation planning (such as bacteria source investigation to help prioritize source controls) and regulatory modification (such as through site-specific criteria) are important tools for communities facing FIB TMDLs.