Comparing Volumetric and Gravimetric Suspended Sediment Concentration Data From a Midwest Stream

This article first appeared in the June 2013 issue of Stormwater.

The ability to categorize suspended sediment metrics (e.g., total concentration, mean particle size, particle size class) to specific land-use types is increasingly appealing in terms of better targeting mitigation strategies. However, innovative real-time in situ instruments that advance monitoring capabilities often provide results that are not readily comparable to traditional analytical methods, and may therefore be limited in application.

Measuring Suspended Sediment

Suspended sediment mass (or gravimetric) concentration of total suspended sediment (TSS) or suspended sediment concentration (SSC) is most often estimated by wet sieving (ASTM 1999, Edward and Glysson 1999, Davis 2005). The main difference between the TSS and SSC methods is that TSS generally analyzes an aliquot of a total sample, whereas SSC analyzes the entire sample. Regardless of the method used, sample collection and laboratory analyses are often expensive and labor intensive (Gray and Gartner 2009).

Recent advances in suspended sediment monitoring include in situ fully automated devices that continuously sense and log suspended sediment and particle size classes. Commercially available instruments include those that use bulk optics (turbidity), acoustics, pressure differentials, and laser optics (e.g., laser diffraction) to monitor suspended sediment (Gray and Gartner 2009). Laser diffraction instruments often provide volumetric estimates of sediment concentration as opposed to a mass concentration (Agrawal and Pottsmith 2000) because the optical power distribution is converted to an area distribution. The LISST-StreamSide (Sequoia Scientific Inc.), which is practical for use in either laboratory or in the field, uses laser diffraction technology to estimate suspended sediment and particle size class concentration metrics. Whether in the field or in the lab, a pump supplies water to the particle analyzer for analysis. After analysis, the water sample can be directly returned to the source, thereby reducing handling and lab processing (Hubbart and Freeman 2010).

Comparing Volume and Mass Concentrations of Suspended Sediment

Methods that can be applied to convert volumetric suspended sediment results to mass results range from applying an assumed particle density to analyzing turbid samples using both methods to establish site-specific relationships (Agrawal and Pottsmith 2000, Pedocchi and Garcia 2006). For example, dividing mass concentration (mg/l) by volumetric concentration (µl/l) produces an estimate of density in mg/µl. Multiplying that result (mg/µl) times volumetric data (µl/l) results in the mass conversion (mg/l). Mikkelsen and Pejrup (2001) used a similar approach in their work to estimate in situ measurements of suspended floc size and density. A simpler alternative is to assume a particle density of 2.65 mg/cm3 (approximate density of silica). In this case, the volume concentration (µl/l) is simply multiplied by 2.65 g/cm3, yielding mass concentration in units of mg/l. The presumptive nature of the latter method could lead to error when other constituents and minerals (besides silica) exist in the sample. An additional conversion method includes regression analysis, in which equations are created [i.e., volumetric (µl/l) versus gravimetric (mg/l) that define relationships in specific water bodies.

The objectives of the following work were to compare gravimetric (mg/l) and volumetric (µl/l) suspended sediment results from a multiuse watershed in the Midwest using a) computation of particle density (Pd) using volumetric (µl/l) and mass (mg/l) results, b) an assumed particle density of 2.65 mg/cm3, and c) regression analysis. The goal was to demonstrate simple methods of conversion from µl/l to mg/l using real data from a Midwest case study to improve comparability and applicability of volumetric results for land management decisions.

Methods

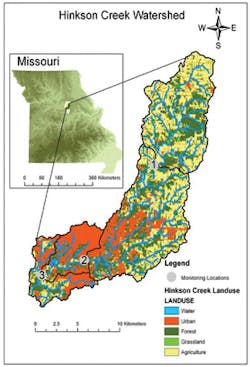

Study Site. The Hinkson Creek watershed (HCW) is located in the Lower Missouri-Moreau River Basin (LMMRB, HUC 10300102) in central Missouri (Figure 1). Hinkson Creek originates northeast of Hallsville, MO, and flows 42 kilometers southwesterly to Perche Creek, southwest of Columbia, MO. Elevation ranges from 274 meters above sea level in the headwater to 177 meters above sea level at the confluence of Perche Creek. In general, soils in the HCW are prairie-forest transitional, poor to well drained, and easily erodible in part due to steep slopes (Perkins 1995). Average discharge from 1967 to 2010 was estimated to be 1.55 m3/s, from data collected at a US Geological Survey gauging station (#06910230) (site #2, Figure 1). The total contributing area draining to the outlet of Hinkson Creek is approximately 230 square kilometers. Site 1 has a contributing drainage area of 77 square kilometers with the dominant land use pasture/row crops (55%). Site 2 is dominated by forested land use (36%) with a total contributing area of 102 square kilometers. Site 3 has a contributing area of 26 square kilometers, and the dominant land use is urban (70%) (Hubbart et al. 2010). Missouri climate is characterized by strong seasonality and is dominated by continental polar air masses in the winter, with summers influenced by maritime and continental tropical air masses (Nigh and Shroeder 2002). Historically, the wettest months of the year are March through June, when 61% (on average) of the region’s annual precipitation falls (Nigh and Shroeder 2002).

Laser Particle Diffraction and SSC Filtration Methods. Stream water grab samples were collected four times a week (Monday, Wednesday, Friday, and Saturday) from March 1 through June 30, 2010, at the same time of day from sampling locations shown in Figure 1. Both laser diffraction (LISST-StreamSide) and wet sieving produced paired volumetric (µl/l) and mass/gravimetric (mg/l) suspended sediment concentration estimates for each turbid sample collected. Particle analyzer settings included 15-second clean water flush, 15-second turbid sample analysis, and 20-second post-sample clean water flush. Samples were mechanically stirred to maintain turbid suspension during analysis. For more information about the LISST-StreamSide, the reader is referred to Hubbart and Freeman (2010) and Agrawal and Pottsmith (2000), who describe the instrument in greater detail. In contrast, gravimetric suspended sediment methods involve collecting a known sample volume and filtering out the sediment using a vacuum filtration process.

Sediment Particle Density and Volume Conversion Analyses. As mentioned, to compare volumetric (µl/l) TSS to gravimetric (mg/l) TSS, an estimate of sediment particle density is necessary. While it is not uncommon to impose an assumed particle density of 2.65 g/cm3 (the approximate density of silica), it may not be appropriate to make that assumption in receiving waters that may transport suspended materials composed of other materials (i.e., organics and other geological material). Regardless, suspended sediment particle density can be estimated if the volumetric concentration and gravimetric concentration of a single sample is known. Using this approach, particle density (Pd) was calculated as:

Then, multiplying particle density (Pd) by the volumetric concentration (µl/l) the gravimetric equivalent (mg/l) was estimated as:

Results and Discussion

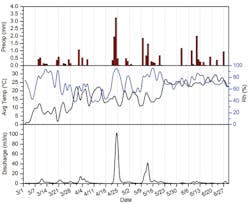

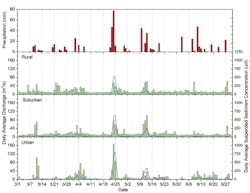

Climate. Total precipitation during the study period was 584 millimeters. Average daily temperature and relative humidity was 17.0°C and 68% respectively (Figure 2).

Average hourly discharge was 2.8 m3/s, 4.7 m3/s, and 6.4 m3/s for the rural, suburban, and urban land-use gauging stations respectively. Figure 3 shows average daily suspended sediment concentration (µl/l), precipitation, and discharge for all monitoring sites during the study period.

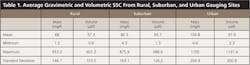

Suspended Sediment Results and Volumetric Conversions. Based on grab sample data analyses, average gravimetric (i.e., mass) (mg/l) and volumetric (µl/l) suspended sediment concentration for the rural gauging site was 68 mg/l (Standard Deviation (SD) =146.1 mg/l) and 57.3 µl/l (SD = 103.5 µl/l) respectively (Table 1). The suburban monitoring site location had an average gravimetric and volumetric suspended sediment concentration of 82.5 mg/l (SD = 163.1 mg/l) and 65.7 µl/l (SD = 126.2 µl/l) respectively. Average gravimetric and volumetric suspended sediment concentration for the urban gauging station was 104.8 mg/l (SD = 204.9 mg/l) and 97.9 µl/l (SD = 200.8 µl/l), respectively.

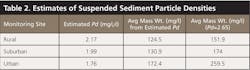

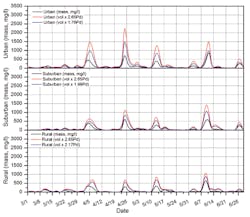

Applying the equations presented earlier, the rural, suburban, and urban gauging sites had average densities of 2.17, 1.99, and 1.76 mg/µl (Table 2). Using calculated particle densities (Pd) daily average volumetric suspended sediment concentration (µl/l) was converted to daily average gravimetric suspended sediment concentration (mg/l). Based on conversions using the calculated Pd, average mass concentration (mg/l) of suspended sediment for the rural, suburban, and urban gauging sites were estimated to be 124.5, 130.9, and 172.4 mg/l, respectively. Based on conversions assuming a Pd of 2.65 mg/µl, average mass concentration (mg/l) of suspended sediment for the rural, suburban, and urban gauging sites was estimated to be 151.9, 174.0, and 259.5 mg/l, respectively. Figure 4 shows a time series of mass concentrations (mg/l) using observed (i.e., wet sieving), estimated Pd, and assumed Pd (2.65, mg/µl).

Results show that assuming a particle density of 2.65 mg/µl led to greater differences between observed and estimated mass suspended sediment (mg/l) relative to using the calculated particle density to make the conversion. When the average computed density of particles was used to convert volumetric estimates (µl/l) to gravimetric estimates (mg/l), there was a 45% difference between observed and converted mass results at the rural site, a 37% difference between observed and converted mass at the suburban site, and a 39% difference between observed and converted mass at the urban site. When applying an assumed Pd of 2.65 mg/µl, there was a 45, 47, and 40% difference between rural, suburban, and urban observed versus converted estimates of TSS. It is worth noting that applying an assumed Pd of 2.65 mg/µl resulted in only a 4% difference between both conversion metrics when comparing overall samples (i.e., from all monitoring sites). However, the differences relative to observed suspended sediment mass (i.e., wet sieving method) and converted volumetric to mass ranged between 37 and 47%, which could lead to significant differences if one were to use the method to calculate total loading. This difference could be overcome by longer data time series including multiple seasons and multiple years, providing impetus for further investigations using these methods.

Researchers suggest that suspended sediment particle densities are commonly between 1.66 g/cm3 to beyond the density of silica (2.65 g/cm3) (Allmendinger et al. 2007, Clifton et al. 1999), the bounds within which the results in the current work reside. Presumably, particle density may be decreasing in the suburban and urban sites relative to the rural site due to increases in organic matter in the water or other anomalies (see discussion below). Agrawal and Pottsmith (2000) suggested that the density of organic matter is commonly around 1.0 mg/cm3, which is considerably less than estimates of mineral particle density. Because suspended organic matter has densities less than sediment, the presence of organic matter could negatively skew particle density estimates. In this study, the influence of organic matter on observed suspended sediment concentration was not investigated. Further work is necessary to understand how organic matter influences laser diffraction estimates of suspended sediment, particle density, and particle size.

Observed mass estimates of suspended sediment (mg/l) were regressed against observed volumetric estimates of suspended sediment (µl/l). This is an attractive technique because there is no need for conversion from volumetric to mass TSS, and thus no requirement of an estimated Pd. Regression analysis resulted in equations that can be used to convert either method. Regression equations were, y = 0.8863x + 5.062, y = 0.7074x + 7.33, and y = 0.6628x + 12.264 for urban, suburban and rural sites, respectively. Coefficients of determination (R2) for rural, suburban, and urban regressions were 0.88, 0.84, and 0.82. The coefficient of determination is a number between 0 and 1.0, used to describe how well a regression line fits a set of data. An R2 near 1.0 indicates that a regression line fits the data well, while an R2 closer to 0 indicates poor fit to the data (Zar 1999). These regression results are compelling, but also indicative of dissimilarity between the data sets.

Method Shortcomings. Some of the possible factors that can influence suspended sediment concentration include precipitation trends, antecedent soil moisture, topography, land use, stream geomorphology, and soil types and characteristics. For example, if particle flocculation is occurring, then applying an average particle density to convert volume to mass will result in an overestimation of the mass concentration. Other explanations for particle dissimilarity may include presence of organic materials, which may lead to underestimation of actual particle density. Particle density may also vary by season, with lower density in the summer (organic material), thus necessitating a seasonal analysis of density to convert volumetric data to mass. Naturally, these factors can vary greatly spatially and temporally, which can confound absolute comparisons of mass (mg/l) and volumetric (µl/l) suspended sediment concentrations. Other methods for estimating particle density, not used in the current work, include particle settling (mentioned earlier) and volatilization (APHA 1995). Ultimately, while laser diffraction can supply novel information, great care must be taken to assure accuracy and precision of results for any management application.

Conclusions

There are a number of innovative devices on the market that collect volumetric suspended sediment data. However, converting volumetric estimates for mass comparisons can be problematic in terms of utility for management decisions. Laser particle analyzers, such as the LISST-StreamSide used in this study, provide estimates of volumetric suspended sediment concentrations (µl/l). To compare volumetric to mass TSS or SSC, particle density of sediment must be assumed (2.65 mg/cm3) or estimated.

The objectives of this study were to use a Midwest case study to characterize and quantify suspended sediment concentrations and to develop relationships between mass (mg/l) and volumetric (µl/l) suspended sediment results. Suspended sediment particle densities were estimated by using results from mass (i.e., wet filtration) and volumetric analysis (i.e., laser diffraction) of suspended sediment. The sample particle density was estimated by dividing the gravimetric suspended sediment concentration (mg/l) by the volumetric concentration (µl/l). Average particle density was calculated to be 2.17, 1.99, and 1.76 mg/µl for rural, suburban, and urban catchments, respectively. The decreasing particle density with stream distance may have been attributable at least in part to the presence of organic matter, which has a much lower density. Despite this difference there was only an approximately 4% difference between converted volumetric to mass suspended sediment using the assumed and estimated particle densities.

What is of greater interest is that there was a 37 to 47% difference between observed average mass suspended sediment (mg/l) and converted mass from the volumetric method, thus clearly illustrating the problematic nature of comparing the two methods and the need for further research. Site-specific regression analysis supplies another technique of correction from one method to the other. However, while results are promising (R2 values 0.82 to 0.88), the method lacks some precision. Additional methods that hold promise may include particle settling and volatilization of solids, providing impetus for continued research. Aside from assuming an average particle density (e.g., 2.65 mg/cm3), the methods supplied in this work hold promise for comparing mass and volume based suspended sediment data, but require site-specific comparisons, which may be labor intensive and fiscally unrealistic. Continued work is necessary to better understand the relationship(s) between mass and volumetric suspended sediment data, the impacts of land use on either method, and the utility of both types of information to advance science and land management practices.