Located on the western coast of Florida, Tampa is situated between two bodies of water: Old Tampa Bay and Hillsborough Bay. They flow together to form Tampa Bay, which joins the Gulf of Mexico.

With its frequent summer afternoon storms, Tampa has a pronounced wet season. An average of 26.1 inches of rain falls from June to September. Tropical storms in early fall can add to this total quickly. Rainfall for the other eight months of the year totals, on average, about 18.6 inches.

“Our climate and our geography bring a lot of rain and stormwater events,” says Jean Duncan, transportation and stormwater services director for the city of Tampa. “We have a high water table, limited land available for stormwater treatment, and a limited height differential.”

Tampa has such low elevation that some places are only 3 or 4 feet above sea level. Duncan says the city has some tides that are higher than that.

She notes that another challenge to managing stormwater in Tampa is funding. “As with many cities, we do not have adequate funding to maintain and expand, to build a bigger system” to meet increasing demands as the city has grown, she says.

Duncan is thankful that Tampa has no combined sewers and isn’t operating under a consent decree from state or federal authorities. However, Tampa has a big problem related to stormwater: flooding.

The city is playing catch-up ball when it comes to dealing with flooding. Despite neighborhoods flooding repeatedly for years, the city council has not been able to pass legislation that would bring in the needed revenue to fix the situation.

“Until 1973, developers built anywhere in Tampa. There were no restrictions,” explains Al Hoel, stormwater chief engineer for the city of Tampa. This lack of building restrictions “left Tampa under a mountain of flooding problems and a mountain of flooding complaints [from residents], and no dedicated funding stream for projects to alleviate the flooding,” he says.

To succeed at catching up with stormwater and floodwater management needs, though, Tampa has one big bat already in hand. City stormwater officials expect they’ll have an even bigger one soon.

The first is the city’s stormwater sewer assessment fee. It was approved by the Tampa city council last year, and the funds are strictly for operations and maintenance.

“Dollar-wise, we’ve basically doubled the amount of funding, compared to what we were receiving,” says Duncan. “We were more or less on a 10- to 15-year cycle of maintaining ditches, pipes, and outfalls. Now with the additional revenue we have moved to a three- to seven-year cycle.”

This increased funding allows the city to take a proactive approach. Besides more frequent maintenance, the fee provides funds for much-need equipment, both new and replacement. That includes an excavator for cleaning large ditches and canals.

Homeowners’ fees are based on the size of their residences. Commercial customers are assessed according to the amount of impervious surface on the property.

The increase in their sewer bills was so small that the majority of residents didn’t notice it. Duncan and her staff, though, are “satisfied with the outcome.”

She says, “We’re barely a year into implementing the increase. In another year we’ll see some real gains with clearing aquatic vegetation in ponds and along banks and ditches. Many outfalls haven’t been cleared in decades. They’re clogged with barnacles and plants.”

The bigger bat that Duncan, Hoel, and the rest of Tampa’s stormwater team expect to be swinging soon carries enough weight—that is, financial clout—to allow them to make a significant difference. It is an additional assessment to collect funds for stormwater capital improvement projects, and it also requires the approval of Tampa’s city council.

The capital improvement projects are large enough to affect neighborhoods and sections of watersheds. “These are huge projects, such as a $40 million, three-year-duration new outfall system in an urban area of Tampa,” says Hoel, explaining that the projects are designed to provide flood relief on a regional basis.

Duncan says the funding “will allow us to do larger, spine-type projects. Later we can connect smaller projects to them.”

“We’ve gone through a feasibility analysis on all of the proposed projects. Mainly, they will be done on a design-build basis,” adds Hoel.

These regional flood relief and stormwater projects total $251 million, to be raised by issuing bonds. The stormwater capital improvement fee will bring in $6.2 million in annual revenue to pay off the bonds. The Southwest Florida Water Management District will provide another $50 million for the projects.

“The city has never undertaken this type of flood relief. It would be quite significant if this is passed,” says Duncan. “It is a somewhat meaningful strike at upgrading and building a system we need to capacity now.”

Flooding was especially bad in Tampa in 2015. Ironically, some streets were so deep in floodwater that residents couldn’t reach scheduled public meetings called to discuss the flooding.

“Last year was off the charts for frequency of storms and rainfall amount, in Tampa and for the state of Florida, too,” says Duncan.

Hoel describes the flooding situation succinctly: “We exceeded our 100-year storm event. Twice.”

“These storm events were not isolated. They were very broad, covering the majority of the city. They had quite an impact on traffic,” recalls Duncan.

Aerial view of the Florida Aquarium

Encore Performance

While Tampa has had to focus on widespread flooding problems that will require major gray infrastructure to correct, the city and Hillsborough County also have some innovative stormwater projects in mind that feature green infrastructure. One of those projects is Encore in downtown Tampa.

An encore is supposed to be something extra, better than the concert it follows. When the Tampa Housing Authority (THA) decided to build a new public housing project, it chose to name it Encore. It also chose to make it live up to the promise of something special, something extra. This Encore is definitely more memorable than the outdated Central Park Village public housing it replaced.

The music theme echoes beyond the new project’s name. The first building, opened in 2012 to provide affordable housing for senior citizens, is named for jazz singer Ella Fitzgerald. Other buildings there include The Reed and Tempo, which is now under construction. Stormwater from the 28-acre property is piped to a storage vault beneath a 16,000-square-foot community park and green space. The vault, made by Oldcastle Precast, is composed of 146 modules that are 10 feet tall (18,000 square feet total). Collectively they hold up to 33,000 cubic feet of stormwater runoff.

The stormwater flows through two Nutrient Separating Baffle Boxes, made by Suntree Technologies of Cocoa, FL, into adjacent sediment chambers and a sand filter system for pretreatment. It is then stored in the modules and used for irrigating landscaping around the buildings.

The stormwater and rain harvesting system was designed by the engineering firm of Cardno TBE of Clearwater, FL. Oldcastle Precast produced the sand filter assembly’s precast perimeter walls, the precast ramp assembly for equipment access into the sand filter, sanitary manholes, and inlets.

The innovative stormwater and irrigation system saves not only money but also space. If THA had installed a conventional stormwater system, three developable sites would have been used for it instead of for more housing.

Another green feature for managing stormwater onsite is the permeable pavers for the center median of the main thoroughfare. They are made by Belgard and supplied by Oldcastle APG.

The general contractor for Encore was Malphus & Sons of Tampa. Project management was done by ZMG Construction of Longwood, FL.

Close to Encore is another innovative stormwater project incorporating green infrastructure. Laurie Potier-Brown, RLA, landscape architect with Tampa’s Parks and Recreation Department, says that the green makeover of Scott Street should be finished at the end of this year.

The city worked with a local landscape architecture firm, Ekistics Design Studio, on the project. Residents were invited to several meetings to choose the green features they liked best. Scott Street’s new design will slow traffic and make the area both more attractive and friendlier to pedestrians.

“They loved the fact that we’re adding landscaping into a hardscape world,” notes Potier-Brown. “They liked the rain gardens and the aesthetic aspect of the permeable pavers.” She adds, “This is our first full roadway with full green street, so a lot of people are paying attention to it.”

Native plants will be a huge part of this project because “we desperately need to not pipe stormwater out [but make it infiltrate onsite],” says Potier-Brown. The trees along Scott Street will include red maples, hollies, live oaks, bald cypresses, and cabbage palms. Other plants will include muhly grass, macho fern, sand cord grass, saw palmetto, dwarf gamagrass, coontie, and dune sunflower.

The Scott Street project was inspired by another green street stormwater project also designed by Ekistics Design Studio. The two-block-long 5th Street project is in the historic district of the nearby Tampa Bay community of Palmetto.

“Fifth Street is an urban, downtown retrofit project incorporating stormwater into all of the green spaces,” says Tom Levin, RLA, principal at Ekistics. “We increased on-street parking and we did not add any conventional stormwater retention ponds.”

Some parking areas have pervious pavement, but large sections of bricks from Pine Hall Brick of Winston-Salem, NC, were also laid as permeable pavers. Where native plants were installed, Levin specified a variety—some preferring more water than others.

Green gutters in the street’s right of way “function like a regular gutter. Water flows into it [easily because] it’s level with the street,” explains Levin.

He adds, “The water flows into a landscaped island, which is notched. When its fills up there it comes back out to pervious pavement until it gets to another green [ section ]. We took the existing pattern of water and interrupted its flow with green infrastructure.”

As part of the project, Ekistics created a design that would include a redeveloped site for a 6,000-square-foot commercial building plus adjoining parking lot and added on-street parking. Even with that additional impervious surface, the design handled stormwater runoff well.

“We were able to prove less runoff and less pollutant level downstream,” says Levin.

Florida Aquarium

The Florida Aquarium’s parking lot and queuing area together are one of three Tampa projects chosen as a Green Infrastructure and Stormwater Management Case Study by the American Society of Landscape Architects (ASLA).

The project was done in partnership with the Southwest Florida Water Management District (SFWMD). With monitoring by SFWMD, the project was designed to reduce runoff and improve the quality of water flowing into nearby Tampa Bay, which is an estuary significant enough to be included in the National Estuary Program.

The location was a derelict industrial area in midtown Tampa. Ekistics Design Studio did site planning, engineering, and landscape architecture for the queuing garden, parking lot, exterior exhibit areas, and administrative areas.

Magdalene Reserve

The project takes a treatment train type of approach to managing stormwater onsite, though Levin says the term “didn’t come into widespread use at that time [and] doesn’t embody the concept of biomimicry” his team was trying to adapt.

“We wanted to do something better than regular stormwater retention ponds, to incorporate that tiered, linear path for water. We wanted to minimize the time the water is just conveyed without benefitting the environment. The whole site becomes the treatment system,” he explains.

The site includes bioswales, a pond, and rain gardens. The swales and rain gardens feed water into a wetland system that terminates in a pond before the water exits into Ybor Channel.

“Ybor Channel is a shipping channel that connects to Tampa Bay. We found an opportunity [to use green infrastructure for stormwater] in the most urbanized area,” says Levin.

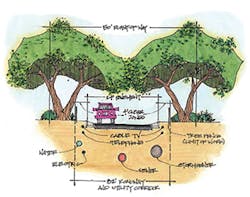

Magdalene Reserve utility placement within right of way

The Florida Aquarium is one of Tampa’s most popular tourist attractions. Parking is essential because aquarium draws thousands of visitors each year, including many children and students. Levin says the project’s biggest challenge was that “the owner said, ‘Great. Let’s do all of these wonderful things—as long as you don’t lose any parking spaces.’”

The Florida Aquarium’s site included 3 acres for the building and surrounding area and 11 acres for the parking lot. The lot contained 950 parking spaces. Finding space for green infrastructure “was a game of geometry,” explains Levin. “We had to ask ourselves, ‘How can we make this space more efficient?’”

No parking spaces were sacrificed for the green infrastructure. The educational signage and monitoring allow the parking and gathering area to enhance the aquarium’s program of environmental education.

“Most of the water was infiltrated. The biggest benefit of the project is that we reduced the stormwater volume and created a new urbanized ecology,” says Levin.

Magdalene Reserve

Levin also designed another Tampa stormwater project that was selected for an ASLA case study. Magdalene Reserve is a single-family residential development that features drought-tolerant landscaping and no conventional lawns.

This project’s first challenge was that “the developer wanted us to still do wonderful things, but don’t spend any more money [than would be expected for a conventional development],” notes Levin. That challenge was met by reducing pavement and utility space. Less money spent on hard infrastructure freed up funds for features that benefitted the environment, such as maintaining the extensive tree canopy and adding green features.

The project’s second challenge was “codes and regulations—layers and layers of things that worked cumulatively to impact the site,” says Levin.

“The water department, the utilities—they all wanted their separate spaces [as they had in conventional subdivisions]. We met with them and dealt with the county and got a number of approvals to waive requirements,” he adds.

The first phase of Magdalene Reserve consisted of 39 homes built on about 15 acres along one main street that ended in a cul-de-sac. In the second phase, 15 homes were constructed on 6.8 acres.

No regular grass lawns mean far less fertilizer and pesticides, which improve runoff quality. A key aspect of this project was working with existing nature, not imposing controls upon it. That overall goal saved site disruption and costs and made this development a model for green infrastructure. Preservation of as much of the existing tree canopy as possible was a priority, not only for appearance and marketability but also for natural stormwater management. Instead of cutting a new road, the contractor turned an existing dirt road into the development’s main street. It curved as often as necessary to spare trees.

On sloping lots, the contractors used more expensive stem wall footings instead of the more typical slab on grade. This choice helped minimize grading and preserve trees.

More than 1,000 oak trees were saved. If Magdalene Reserve had a conventional subdivision design, most of those trees would have been cut down and only 200 would have been left standing.

The oak trees, plus magnolias, palmettos, pines, and other native species and native understory vegetation, yielded a drought-tolerant landscape. In Tampa’s tropical climate the shady tree canopy and the natural preserve near the entrance provided welcome wildlife habitat.

Impervious surface was reduced whenever possible to increase infiltration of stormwater runoff. One strategy was installing a sidewalk on one side of the street instead of on both sides, which required a waiver from the Hillsborough County zoning and planning authorities. Another reduction of hard surface occurred when some of the homes were situated so that they would share driveways. This practice reduced grading and removal of trees as well.

Cotanchobee Fort Brooke park

Allowing for unconventional access to lots reduced roads and utility lines by 20% in length. Cleared rights of way were reduced by 50% in width.

All utilities at Magdalene Reserve fit into a 32-foot-wide corridor, compared to Florida’s typical 50- to 70-foot-wide corridors along streets. The utilities not under the road have to be in a 4-foot-wide strip on either side of the road

Swales were installed along the edges of backyards, by wetlands. Stormwater thus does not have to be conveyed to the street, reducing both costs and environmental impact. Adding the bioswales and reducing the amount of paving allowed for the required detention ponds to be smaller. The two ponds were installed in low areas on either side of the road near the entrance. They can hold runoff from up to a 100-year storm event.

A landscape maintenance service takes care of all of the plants, including those on private property. This uniform approach ensures minimal use of fertilizer and water.

Using green infrastructure to manage stormwater at Magdalene Reserve cost about $100,000 more than doing it by conventional gray infrastructure. However, clearing fewer trees and installing less paving and fewer utility lines resulted in savings of $75,000.

Innovative design permitted two more lots (each worth $60,000) to be created. These strategies combined to total savings of much more than the additional initial cost of choosing green infrastructure over gray.

Magdalene Reserve was developed by Tampa Housing Group, a partnership of Mobley Land Co. and Klingbeil Companies, both of Tampa. Civil engineering services were provided by Florida Technical Services of Tampa.

Cotanchobee Fort Brooke Park

Since the 1950s, about half of Tampa’s natural shoreline has been lost to waterfront development. That loss has resulted in a loss of wildlife habitat and decline in water quality. Restoring the natural shoreline whenever possible is an environmental priority.

Cotanchobee Fort Brooke, an attractive municipal park in downtown Tampa, is situated between a busy boulevard and Garrison Channel, which connects to the Hillsborough River. Almost 2.5 of the park’s 6.3 acres were involved in a revitalization project. A Tampa engineering and landscape architecture firm, Hardeman-Kempton & Associates, was responsible for the design of the project.

To restore part of the park’s natural shoreline, an existing seawall was removed and the bank was graded back to its natural slope. Native plants were installed in plant beds, and native shoreline plants formed the new natural shoreline.

Brad Suder, director of Tampa’s Parks and Recreation Department, says the park’s system “captures stormwater in the park’s plant beds and conveys it to scrubber marshes.” Then the runoff is “discharged into spreader swales, ultimately sheet-flowing over a restored vegetated shoreline into the Garrison Channel.”

Southwest Florida Water Management District’s SWIM (Surface Water Improvement and Management) program was the major source of funding for the $1.5 million dollar project. SFWMD requires that littoral shelves be vegetated to at least 85% and 30% of the surface area of a pond. These plants prevent algae from getting established in shallow ponds or along shorelines.

New funding means the city of Tampa can begin installing much-needed major watershed and neighborhood stormwater projects that will alleviate its serious flooding problems. Innovative green infrastructure projects such as those profiled above will increase as well.

One such project will be at Tampa’s Lowry Park Zoo, which leases land from the city. The zoo’s animal wastewater treatment plant currently sends water to a stormwater pond, which is undersized. Overflow runs into the Hillsborough River, causing this section of the river to become polluted.

Hoel says a year-long study was performed that points to a solution. “If the water going to the pond is treated to a higher level and the zoo installs an underground vault adjacent to the pond, then the water can be recycled onsite to wash the animals’ habitats.”

The zoo is raising funds for this upgrade. Hoel says that using stormwater this way “will clean the polluted part of the Hillsborough River and save money by recycling water.”

The city’s Stormwater Division got involved “because our vested interest is in water quality,” says Hoel.