A New Life for Denver's Historic Irrigation Ditch

A Reimagined Future for the Historic Canal

Today, the Canal is in a time of transition, as water scarcity and unprecedented growth in the region, combined with the inefficiency of delivering water in an unlined ditch, has precipitated the need to reassess the use and future role of the Canal. Currently, the Canal is a costly and inefficient means of delivering water; on average, 60 to 80 percent of the water diverted to the Canal from the South Platte River seeps into the ground or evaporates. Denver Water, the Canal's owner, is now transitioning irrigation water customers to a more sustainable water source and capitalizing on an opportunity to bring local partners together to chart a new life for this regional legacy.

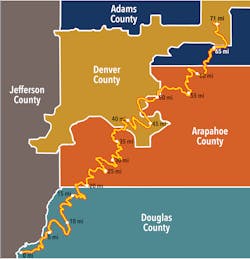

Today, the Canal's transition to green stormwater infrastructure is underway. To date, five stormwater projects have been initiated along the Canal, formalizing the inflow of existing stormwater and, in some cases, adding additional inflows. These projects incorporate over 10 miles of the Canal into municipal stormwater systems, improving water quality and conveying stormwater while enhancing the ecological health of the Canal corridor. These projects are just the beginning, as 62 of the Canal's historic 71 miles are eligible to be transitioned for stormwater management.

"The historic story of the Canal and its beginnings was like a promise of a better future," said Tracy Young, City of Aurora and High Line Canal Conservancy Board Member. "Those who used it were able to enhance their lives and enhance their property. This is a new way for us to bring that promise today of a new future."

Assessment and Recommendations for the Canal's Stormwater Transformation

The Canal cuts across drainage basins crossing 32 creeks and gulches and, in many instances, intercepts stormwater before it returns to natural waterways. The stormwater operations and master plan, completed in 2018, analyzed the infrastructure needed to formalize existing inflows of stormwater, providing for water quality and addressing risks of localized flooding.^1

The master plan also addresses the Canal's risk of overtopping in 47 locations and recommends improvements to mitigate this risk. The master plan includes a hydraulic model that analyzes the capacity of the Canal, identifying locations where the Canal lacks freeboard during a 100-year storm event. In these locations, the master plan proposes constructed overflows and formalized channels or spillways to direct excess water back to natural waterways while protecting people and property. In some instances, the master plan recommends raising the Canal's embankment, ensuring sufficient freeboard to convey stormwater during significant storm events.

While the master plan recommendations facilitate the formalization of stormwater flows that currently reach the Canal, an important part of the Canal's stormwater future is the potential to capture new inflows where the Canal has sufficient capacity. Three of the five stormwater projects along the Canal were initiated to allow for new stormwater flows from nearby developments or redeveloped properties. That stormwater benefit is even reducing the need for new stormwater infrastructure, such as piping and detention, that some developments and cities would have been required to build, thus providing cost savings.

For the 500,000 users of the Denver Metro Area that recreate on the High Line Canal trail every year, the Canal's transition to green stormwater infrastructure brings with it the promise of enhanced ecological health, climate resiliency and community livability. While working to advance stormwater projects, the Conservancy has expanded its focus in the last two years to evaluate the varied social, economic and environmental benefits that can be realized from this transition. Working with governmental partners, the Conservancy developed a stacked benefits analysis and is currently working with U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) to apply their Augmented Alternatives Analysis.

Concerted Planning to Secure a Brighter Tomorrow

The results of these analyses are clear: in addition to providing for water quality, conveyance and localized flood mitigation, managing stormwater in the Canal will support a vibrant tree canopy, reduce the urban heat island effect and enhance the health and well-being of nearby residents who can utilize this recreational amenity right in their backyard. Furthermore, these results are even more stark when comparing the performance of the Canal as green stormwater infrastructure to the potential that stormwater would be withdrawn from the corridor and managed offsite. By removing current inflows from the Canal, the loss of trees, riparian land cover and potentially even trail users could cost local governments significantly more than incorporating the Canal as a part of their stormwater management systems.

"The Canal provides an incredible opportunity for our region to repurpose aging infrastructure in a sustainable, forward-thinking way," said Harriet Crittenden LaMair, Executive Director of the High Line Canal Conservancy. "The transition of the Canal will help preserve a piece of Colorado history in perpetuity using modern-day modifications to allow for stormwater conveyance."

In a state long-plagued by water scarcity and a region that has doubled in population in the last thirty years, the Canal is proof that more can be done with less through deep collaboration, thoughtful planning and strong commitment. Thanks to the foresight and leadership of the High Line Canal Conservancy, Denver Water, Mile High Flood District, local governments, and stormwater districts, a new life and renewed utility are coming to the Denver region's most cherished greenway. SW

Josh Phillips is the Director of Planning and Implementation with the High Line Canal Conservancy and Cathy McCague is the Conservancy's Stormwater Project Manager. The Conservancy was formed in 2014 to preserve, protect and enhance the High Line Canal in partnership with the public.

References

1. "High Line Canal Stormwater and Operations Master Plan - Final Report," RESPEC Consulting & Services, Denver, CO, 2018, pp. 1-161.

Published in Stormwater magazine, May 2021

About the Author

Josh Phillips

Josh Phillips is the Director of Planning and Implementation with the High Line Canal Conservancy, which was formed in 2014 to preserve, protect and enhance the High Line Canal in partnership with the public.

Cathy McCague

Cathy McCague is the High Line Canal Conservancy's Stormwater Project Manager. The Conservancy was formed in 2014 to preserve, protect and enhance the High Line Canal in partnership with the public.