You slipping on a banana peel is comedy.

Me slipping on a banana peel is tragedy.

—Groucho Marx

The nation’s first stormwater utility was established in 1974. Since that time, many successful stormwater utilities have been reaping the benefits of dedicated revenue to appropriately manage their stormwater needs. Some of these utilities were challenged legally in court but upheld. All were challenged in the more exacting court of public acceptance.

Not all stormwater utilities succeed. This article addresses the 10 most common reasons stormwater utilities fail. I thought of writing an article on the top 10 ways to succeed. But it is often more instructive, if not more interesting, to be a stormwater crime scene investigator than a theoretical stormwater student.

So bring up the music, let the Florida sunrise fill the screen, strap on your detective gear, get your polymerase chain reaction DNA analysis kit ready, and let’s investigate a few stormwater utility crime scenes.

Defining Failure

To fully understand success, it is necessary first to understand what we mean by failure. There are perhaps two major ways that stormwater utilities fail.

Failure to Initiate

Dipping your toes in the water and deciding not to swim is not failure—it may, in fact, be wisdom. Failure to actually come to completion as a stormwater utility is not failure. However, unexpectedly and badly failing to initiate a stormwater utility is failure. What I mean by this is that we often begin the process of establishing a stormwater utility but make a calculated decision not to proceed. It may begin with a does-it-make-sense (DIMS) study, a feasibility study, or a stormwater business plan that has a financial component. The DIMS study is a one- or two-day, fast-paced, and low-cost approach designed to stimulate both discussion and interest about the concept of a stormwater utility among staff and potentially recalcitrant political leaders. It asks and seeks answers to a set of key questions necessary prior to a go–no go decision. It is also low risk. It is dipping our toes in the water. Many smaller towns and cities take this route first.

The feasibility study, or business plan, is a longer and more involved study that actually builds momentum toward stormwater utility acceptance and implementation while it explores similar questions. It often involves a citizen group.

Both of these study types, when done right, are foolproof. By that I mean that you cannot fail. If, on the one hand, it is found that the utility is a good idea, the study is a success. On the other hand, if it is found that a utility is not a good idea at this time or another form of funding is appropriate, the study is equally successful. It did its job in smoking out reasons not to go forward and the idea is set aside peacefully without embarrassment, recrimination, or negative publicity. It was a success.

I personally have been involved in more than 30 such studies. Often, in the course of stormwater business planning, a sound program path is created, support is built, and, in the end, another funding package (taxes, one-time fees, property transfer tax funding, sales tax, tax increment funding, GO bonding, etc.) not including a stormwater user fee is preferred. I should go on record saying that I believe that a stormwater user fee, like a water and wastewater user fee, is in the end the best long-term solution for most comprehensive stormwater programs and that by 2020 there will be 10,000 such utilities—one for each town and urbanized county with more than 10,000 in population. The advantages of such an approach are just too overwhelming.

However, the landscape is littered with aborted attempts to establish a stormwater utility that did not follow a thoughtful and careful process and proceeded down the expert ski slope with a beginner’s skill level. You sometimes make it. But it is high risk and low probability, and when you fail it is often spectacular—at least for the municipal beat reporter looking to sell papers.

One of the main reasons we fail to initiate is that we fail to understand there is a political and human process for bringing about change. The process does not ignore us, even if we ignore it. There is a simple model that defines the potential for success in any human system change endeavor. Its usefulness and simplicity of applicability has been proven, at least in the author’s experience, many times in widely varied situations and through more than 20 years of setting up stormwater utilities. The model is a simple “equation,” ∆ = D * V * P, where ∆ is a measure of the potential for successful introduction of a user fee; D is a subjective measure of the degree of dissatisfaction with the current status quo or desperation of felt need for change; V is a subjective measure of the compelling-ness of a vision for the future (it defines a different stormwater program in ways that provoke a desire to move from the old paradigms to better ones); and P is a subjective measure of the appeal, practicality, and reasonableness of the plan to move from D to V.

I have seen over the years that there is indeed a multiplication effect that takes place when all three elements are effectively in place. So, for example, a community can be very and clearly dissatisfied with its current situation (say a 10 out of 10), can have heard of and talked about some good ideas on things that can be done differently (say a 5), but can have no viable plan to move ahead or a consensus to do so (say a 0). And the resulting multiplication is zero. The effort fails. The goal is to try to take each of these key elements to as near a 10 as possible—to “bat a thousand.”

Failure to Meet Reasonable Expectations

The second, and subtler, way in which utilities fail is in the failure to form an entity that meets performance expectations. Sometimes impossibly high expectations are created unintentionally during the setup process itself, but most often they are simply the expectations of a reasonable citizen anticipating effective stormwater service.

Possibly the program is slow to attain results, is underfunded, or is hampered in other ways leading to citizens’ frustration as they pay their stormwater bills but do not realize improved service. It may be that the utility is targeted to handle only one aspect of a comprehensive stormwater program (e.g., National Pollutant Discharge Elimination System, or NPDES, compliance) and thus cannot handle citizen flooding or maintenance complaints. It may be that a lot is being done but not appropriately publicized. This often then leads to bad feelings, angry phone calls, and a public black eye. In a case or two, it has led to repeal of the stormwater utility itself. Once trust is lost, it is very hard to regain.

Top 10 List

There are many specific reasons utilities fail. Over the last 20 years of practice, I have come up with my favorite Top 10 List. So, with apologies to David Letterman, here they are. I’ll start with the least common or explosive and move toward the spectacular. See if they resonate. Get out your fingerprint brush.

Reason #10: Our database was messed up without the ability to easily fix problems.

Billing is all about three things: (1) getting almost all the bills right the first time, (2) handling customer complaints and inquiries with polite efficiency and smart policies, and (3) quickly admitting when you are wrong and making things right with alacrity. Of course, it helps in the first place that your public education program was effective and that the rates actually make sense even to your brother-in-law.

Getting things right the first time places great reliance on the basic rate methodology to define required accuracies and precision and to measure what you say you are measuring. I have learned that many MIS personnel have an amazing ability to answer your question correctly from their perspective but incorrectly from yours. That is because none of their databases is actually intended to produce an impervious layer suitable for stormwater billing. Figure 1, for example, was one MIS director’s affirmative answer to the question, “Do you have an impervious coverage?” (Names and locations throughout the article have been obfuscated to protect the author!) I have tried since sixth-grade mathematics, and you simply cannot find the area of a line—even if it does surround an impervious parking lot.

A Southern county decided to bill on the basis of current zoning (Figure 2). This, of course, led several farmers, who had obtained industrial park zoning for their farms in anticipation of a secure retirement, to receive bills of many thousands of dollars. For example, the property on the right of the photo is coded correctly, while the farm on the left is not. When the farmers called, they were shuttled from department to department with little chance of appeal. Needless to say, the utility (and county engineer) eventually went down in flames with refunds of all bills.

One Western town used satellite data with little correction and a rate structure “measured” to the nearest 10 square feet of impervious area. In the end, the rate structure could not be supported by the data accuracy, generating errors and complaints that were unacceptably high. When the calls started coming in, the partially trained temporary staff members were so overwhelmed that they simply began forwarding calls to the next available staff person, relevant or not. A simple adjustment to the rate structure would have solved the problem and increased revenue at the same time.

Smart policies and polite customer service will go a long way. And you will be skewered when they are lacking. One Midwestern city billed one year in arrears without warning, had inadequately trained customer service capacity, and had a database riddled with mistakes. The $14,000 bill to a particularly well-connected and poorly treated resident made the front page, leading the city to decide that, indeed, not all publicity is actually good publicity.

As a fix, AMEC Earth & Environmental Inc. established a hybrid public-private stormwater customer service system with the ability to automatically generate a digital picture of each property with the impervious layer and various statistics superimposed on it (Figure 3). The picture could be e-mailed to the customer in real time during the course of the call to solve problems. A Web-based system was established to allow customers to look at their own property and billing information online.

Another Midwestern town billed on the tax bill and, because there were no accounts for nonprofits, simply chose not to bill them—leading, after long foot-dragging, to embarrassing explanations and hand-establishment of a separate billing system.

Reason #9: Our program or performance did not meet community expectations.

In my experience, there are several ways to succeed at this kind of failure, but one is most common: having a program that does not scratch people where they itch in a timely way. This can happen in several ways.

The first is to have a rate structure that has a singular focus in a world that has multiple problems. It then generates too little revenue to actually construct needed improvements and is mismatched fatally with customer expectations. There was a stormwater utility in the South that was established, despite internal misgivings and external warnings, to only partially meet the unfunded mandate of NPDES Phase II. It went forward with a user fee of less than $0.50 per month. Now it is under fire for not meeting the perceived needs of its customers and for wanting an almost doubled rate increase…which it desperately needs in order to actually meet the needs of the customers. It was put in a difficult catch 22. Explaining this programmatic nuance to a shark-infested pool of citizens and reporters turned into a public bloodbath.

A second variation on this theme is simply to replace general fund sources with user-fee sources without actually improving the stormwater program. This has led several cities to repent in dust and ashes as the flood of citizen calls came in demanding better service for their new “rain tax” and not being in the least satisfied that it was simply a more equitable way of billing for an existing, and underfunded, service. This is especially embarrassing when there is no actual tax rebate to offset the new fee.

The third variation is to have a program focus that does not produce brick and mortar in the field. People do not want to pay to plan, to be regulated, or to be educated. They want problems fixed—but good. Every city has capital needs that do not need master plans or prioritization schemes to fix; everybody knows they are the most important. So while we are planning, we should be fixing. In addition, people do not know whether the dirt that is being moved is million-dollar dirt or $40,000 dirt. So use your limited funds to move $40,000 dirt in lots of visible places, not in one $1 million place. By the way, it goes without saying that if those many places just happen to be situated, one each, in every council district, with the local council members cutting the ribbons on much-needed projects, you will get more council support.

Fourthly is delay in scratching the itch. A utility in the Midwest promised that there would be several million dollars in capital investment and several new maintenance crews in the first year of operation. After three years, it still had not attained this impossibly aggressive schedule. The customers were howling for the head of the director and for council to pull the plug. The planners and consultants failed to realize that their staff, used to drinking from a trickling garden hose, could not efficiently handle the flow of revenue from a fire hose when the utility was switched on—and that things take time even while revenue is accumulating. Only a generous “warm and breathing” credit saved the day and reduced the bloat.

Reason #8: Our rate structure unexpectedly limited our ability to move forward with our program.

This is a little like the last one but has an important difference. Many towns and cities operate on the premise that some money is better than no money. And so they work a deal in the rate structure giving away credits, reductions, exemptions, and rate caps indiscriminately. This works fine as long as some limited program is better than no program, and as long as “surely our citizens will understand” also prevails. The problem is that, when someone’s property is flooded or his or her garage is eroding away, nuanced understanding often is replaced by blind rage.

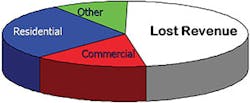

For example, in order to “get started,” a town in one state decided to artificially cap the charges to non-residential property. Citizens, being charged $3.50 a month, did not find it important to sue on the basis of break in rational nexus of the charges. Businesses who were undercharged, and knew it, also did not challenge the fee. Smart, huh? However, as illustrated in Figure 4, the utility staff and consultant failed to realize that in a normal city or town fully 60% of the revenue should have come from non-residential properties. They thus created, through the monthly residential stormwater bill, the expectation of an effective stormwater program without the revenue-stream reality to deliver. Three years later, they were worse off politically than if they had never set one up at all.

In another state, it was decided by a number of communities to charge a “water-quality fee” or a “clean-water surcharge.” First of all, the very idea was challenged in court as illegal. Secondly, the small charge simply aggravated citizens when their need for stormwater services—their itch—was not able to be scratched by the severely limited revenues earmarked for something else. The phone calls eventually overwhelmed one city engineer, causing him to move on to greener pastures.

Another city had promised not to raise the rate for seven years, locking it into a program that could not meet the demand its effective public awareness program had created. The city began with about 500 complaints and, after completing 500 projects, had a backlog of 700 legitimate complaints as citizens who long ago had given up calling began to dial City Hall again.

I recall one young engineer telling me that he was almost shot when he told one flooded resident that, as a cost-saving measure, the city had opted not to go off the right of way with maintenance or flood control services and that he could not help the person even though that resident’s property was flooded by city street runoff. The city lost the lawsuit because public street water flooding downstream citizens is no different from any upstream development flooding a downstream development. It led the city to take a more proactive stance in identifying its “public” stormwater system as anywhere public water flows.

Reason #7: We didn’t prepare our elected officials for vocal complaints.

No matter how good a job you do with public education, unless you have Kiefer Sutherland turn in the middle of a tense scene in the television show 24 and tell people about the stormwater fee, many people will not know what the fee is until they are asked to pay it. Thus it is important for you to help elected officials see the light long before they feel the heat. They need to be educated, armed with facts, and made to look like heroes stewarding the infrastructure, protecting the environment, defending against federal intrusion, and guiding development. This is what happens when you don’t:

- An eastern city did a poor job both in public education and in control of political leadership expectation. When the calls came in, the political leaders were not armed with appropriate answers to tough questions or with a set of compelling reasons for the new “rain tax.” They pulled the plug and lined up at the podium to denounce the poor public works director whom they had told to “establish the fee and get us some money” months before.

- In a recent news article, a small town council in North Carolina, feeling exposed and unable to justify the rate, publicly voided a stormwater user fee, saying, “There were a number of things we missed in the setup—we did not want to miss them,” which turned out to be code language for “Watch the heads roll.”

- The pressure on the political leaders in a Western county was such that each of them stood up in the meeting set to adopt the ordinance and surprisingly (at least to staff) denounced the stormwater fee as unfair and unfocused.

Also think timing. No elected official wants to fall on the knife for stormwater. A Western town that delayed in executing a contract to implement a stormwater utility found that pushing the utility campaign into the political “silly season” caused it to become a political hot potato, eventually losing the support of the several incumbents and causing its demise.

Reason #6: We couldn’t explain our program and funding strategy or rates.

Keep it simple. Keep it intuitive. Keep it explainable to an eighth grader.

All stormwater rate structures are made up of three components: basic rate methodology, secondary funding methods, and rate modifiers. There are hundreds of combinations, and a bit of tailoring is always is order. But there is an inherent logical simplicity to stormwater user fees: “The more you pave, the more you pay.” Because we are so smart, we want to forever tweak the rate structure to improve equity and reflect all sorts of added factors. First of all, each additional factor increases complexity and cost—both at first and in long-term maintenance. Secondly, it begins to lose the intuitive nature and becomes the sort of thing people simply throw up their hands over when it initially is explained by the proud but misguided rate expert.

For urban development (as opposed to agricultural land), imperviousness is the single most important factor reflecting increase in the three biggest categories of urban impact: peak flow, pollution, and flow volume. The courts have stated again and again that mathematical exactitude is not necessary for rational nexus to exist. We should get more complex only when we have to, not because we are smart enough to. Here are a few examples:

- A western county had a rate structure that was so complex, seeking to reflect various kinds of pollution loading, that it was difficult to explain it to those with questions and would have been a nightmare to maintain and defend in court.

- • A southern state, in a fit of political cover, passed legislation mandating that this statement appear on each stormwater utility bill: “This tax mandated by Congress,” which would be true, except it is not a tax and it is not mandated by Congress.

- A mid-southern city, on the basis of a detailed and very convoluted rate study done by a Big Eight accounting firm, decided to charge homeowners a fee of more than $8 (reasoning that is what the numbers showed) while exempting large industrial and commercial sites on the basis that they were direct dischargers to a local river. Needless to say, council fell all over itself lining up to vote against the utility and defend the poor homeowners.

- A southern county decided to master-plan for the first five years of the stormwater utility in order to have a sound and prioritized capital plan. When it hit the papers it sounded like bureaucratic mumbo-jumbo and red tape in actually getting things fixed. It did not help when a spokesperson could not explain the facts in front of a public meeting, while the ones who knew what to say died a thousand deaths in the back of the room.

Reason #5: We didn’t involve the community early enough or in the right ways.

There is one key rule of public involvement: “Bring me in early and I’m your partner. Bring me in late and I’m your judge.” We all know there are many “publics” and many ways to get messages out. Political leadership wants “more fingerprints on the knife” when they stand up to vote for a new fee. They want others to have suggested or, better, demanded it first. Key to success is not skimping on one-on-one efforts and having a detailed plan covering the who, what, when, and how of getting key messages to the right people in the right ways. It doesn’t have to be painful involving the public. But it often is.

- In the eleventh hour, a group of developers did an end run around the team developing the utility and, not being invited to the table, convinced the mayor that this was a bad idea and an attempt to “put something over” on the public.

- A southern county developed a citizen group made solely of environmental proponents and flood victims. Needless to say, the backlash from the rest of the legitimate stakeholders was intense, sinking all efforts.

- A Midwestern town failed to keep its key staff leaders in the loop, causing them to make unfortunate statements about the size of the fee and forcing a cutback in the planned program and the effectiveness of the effort.

- As Figure 7 shows, in Charlotte, NC, the result of investing several meetings with the local editorial board helped head off a last-minute delay tactic by a developer group.

Citizen groups also can be high risk, but not if suitable controls are in place.

- “In 30 years of public service, this is the single most fulfilling thing I have done.” So ended the last meeting of the stormwater advisory committee in a southern town.

- “If this is the way things are going to be, I’m in.” So the threatened lawsuit in a large eastern city was dropped by a satisfied citizen after a wonderful welcome dinner and an efficient and effective group kickoff meeting.

- “I’d like to propose a toast…to stormwater management.” Lots of laughter. That is how the mayor kicked off the first of six meetings with a select group of local leaders over steak grilled by the public works department.

It can work. See my article “Developing Technical Policy With Citizen Groups” for more details on those suitable controls (Reese 2002).

Reason #4: It was not legal.

We always assume we will go to court—and we intend to prevail. In every utility project I have done for the past 10 years, I always tell my clients from the point of the first greeting onward that they should not write, e-mail, or note anything they would be embarrassed to have their mother hear in court, or worse, read in the headlines. As stormwater utilities proliferate, court cases in states where they proliferate become less and less common—unless someone tries something that appears to be both illegal and harmful to a customer willing to sue to settle the problem. In the many states where utilities are just gaining a foothold, things are different. Stormwater management program fees have been the subject of litigation resulting in reported opinions from at least 17 states, including many cases involving final decisions by the state’s highest court (NAFSMA 2006):

- Montana—1966

- Colorado—1986 and 1993

- Kentucky—1989 and 1996

- Ohio—1990

- Oregon—1992 and 1993

- Kansas—1994

- Florida—1995, 1998, and 2003

- Washington—1997

- Virginia—1998

- Tennessee—1998

- Michigan—1998 and 2001

- North Carolina—1998 and 1999

- South Carolina—1999

- Alabama—2001

- California—2002

- Georgia—2004

- Illinois—2005

When you go to court, it is important to have an airtight approach and to have met several critical tests of legality. Remember that there is a considerable legal difference between a tax (designed primarily for revenue generation without regard to rational nexus); an exaction (where someone pays a price to obtain a benefit from the city, like an impact fee or a franchise fee); an assessment (such as a capital assessment district where direct and special benefit is key); and a user fee (where rational nexus between the charge and the use of the system—not benefit, by the way—is key). If it is a user fee that you are attempting to develop, then there are certain rules that must be followed.

- A western city attempted to impose a stormwater fee but was unable to prove the fee was not incidental to property ownership—and thus a tax—thus subjecting it to a citizen vote.

- A northern city in a non-home-rule state started down the utility pathway only to find out late in the process that its local attorney did not feel it had legal authority to establish such an entity, thereby causing some embarrassment as it pulled the plug on efforts.

- A Midwestern city failed to prove that the fee was legal and appropriate for federal facilities using an argument that may not have taken full advantage of appropriate precedent or key legal arguments that did have sufficient precedent.

- An eastern city billed stormwater fees on the basis of water meter size. This lack of rational nexus created a situation wherein lawsuits were filed and citizen support was low.

- A Midwestern city, deciding that stormwater credits might take away too much revenue, failed to offer such credits and lost the utility in court, partially on the basis that there was no recognition of reduced usage of the stormwater system—no way to “refuse service.”

There are a number of bases for lawsuits, the most common being the following:

- The rate is not perceived as being fair and reasonable.

- It is seen as illegally discriminatory or confiscatory.

- The costs are not seen as substantially related to provision of facilities and services.

- The rate is not based loosely on demand.

- The rate is not legal by charter or legislation.

- Funds were not segregated and dedicated to stormwater.

- Proper procedures were not followed, such as Sunshine or public noticing provisions.

- There was no “opt out” provision created through crediting.

Reason #3: We didn’t understand the process.

Most successfully developed stormwater utilities follow along several interrelated tracks of effort: program development, financial analysis, database and billing development, public education and involvement, and governance structure. These should operate in a coordinated way for things to go smoothly.

For example, the rate structure should reflect basic decisions about the program components and directions. The rate methodology should reflect both the availability of data and the drivers for the program. Certain policies on extent and level of service must precede decisions about cost and rate—but must not be done blindly, forcing a higher rate than the citizenry will bear.

There is an established order of things in the establishment of a stormwater utility. This is what can happen when you don’t know or follow it:

- A Midwestern city simply developed an approximate fee and began billing, only to find out later that it had not followed legal process or appropriate due diligence. It canceled the fee and issued an apology to citizens.

- A Midwestern city decided, on the basis of a political deal, to charge an amount less than it needed and simply wrote the amount into an ordinance. When called to justify the rate, the city found that all the necessary studies were lacking—as was its legal basis for the utility itself.

- A southern city developed the user fee based on a funding shortfall in its local budget and began to establish it without resorting to an appropriate cost-of-service analysis or rate structure. In district court, the fee was disallowed as a tax, causing a refund with interest.

- A western city decided to charge a small surcharge on a water bill because it was easy. Today the city is still stuck with this fee as its only funding source after council improperly reasoned that the city “got its fee” and moved on to other things.

Reason #2: We didn’t present a true compelling case.

In the change model discussed early in the article, the first component is “D”: desperation for change. We call that making a compelling case for change. What is your compelling case—not your compelling case personally as a staff wonk, but what is Mrs. Minerva Schmedlap’s compelling case? If it doesn’t sell in the neighborhoods, it will eventually not sell downtown.

- A Midwestern city stated that the reason for the utility was that the federal government was requiring it. When it was found out, an embarrassing (and entertaining) set of news articles documented the dance to avoid embarrassment and acknowledgement of the error, thus reducing the fee and causing a couple of lost elections.

- A southern county tried to sell the need for the user fee on the basis of staff-felt needs rather than citizen-felt and -generated needs, causing a very tough technical sell to the public and eventual defeat of the utility resolution in council.

- A Midwestern town tried to explain the fee by saying it was “out of money,” causing a backlash among low-income citizens who said they, too, were out of money but had to live within their means.

In every community there are good, even compelling, reasons to change the way things are done. It might be a beloved stream that is becoming increasingly impacted by upstream development, a lack of riparian park space, decaying drainage infrastructure and mounting complaints, unfunded regulatory mandates, local flooding, mounting financial pressures, loss of fish, beach closings, a roadway or bridge collapse, lawsuits, etc. Some are compelling and core in that they draw people, key stakeholders, and leaders to opportunities and to solve visible problems. Some are more tolerated and change comes but more grudgingly.

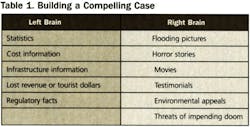

Assembling a “compelling case” is the first step in bringing about change. People in general are motivated along two complementary sources of argument—people are essentially “left brain” or “right brain.” Left-brain people want facts and statistics. Right-brain people are moved to action by horror stories and pictures. So when we begin to quantify and qualify the level of dissatisfaction, and to stir it up, we seek to address both sides of the brain (Table 1).

Building a compelling case and knowing when, how, and to whom to present it is more of a political and technical art form than a learned skill. But taking time to build informed consent that there are sufficient problems to move forward, and building support for change, is vitally necessary.

There is a generic set of drivers we have discovered over the years that can contribute to any city needing to look to a user fee. Not on that list are “We are out of money,” “The government is making us do this,” and “You will get a tax break.” On that list might be things such as flooding or water quality.

Reason #1: We did it the convenient and inexpensive way, not the right way.

Perhaps the one key to success that flows through all of the Top 10 is something called due diligence, not just legal due diligence but in every aspect of the project. Due diligence is important along the five “tracks” or major areas of concern mentioned above:

- Program: Does the program make sense? Is it compelling? Is it within ability and willingness to pay? Does it meet citizen perceptions? Is it action oriented?

- Finance: Are legal tests satisfied? Is it simple yet fitted to the local situation? Does it have the perception of equity? Are proper steps followed? Does it support the stormwater program?

- Governance: Are the partners to the utility and the stormwater program appropriately involved, supportive, and sensing that the end result will be both equitable and effective?

- Public: Are there appropriate levels of involvement of key stakeholders? Is the general public correctly handled? Is the media appropriately involved? Is customer service accounted for? Are staff and political leadership elements accounted for and appropriately handled?

- Database: Is the database accurate within legal requirements? Is there an appeals process? Is it maintainable within reasonable cost constraints? Are anomalies accounted for? Is customer service appropriate and responsive?

With appropriate due diligence in mind, a process can be developed that accounts for bringing about change and effectively and efficiently implementing a stormwater utility. When you don’t:

- A southern county billed on the basis of zoning classification in a county where zoning and on-the-ground reality had only a passing relationship. Because of the inaccuracy in the bills, the utility eventually failed, resulting in a refund of the money collected.

- A Midwestern town decided to forego investment in a public involvement campaign, only to find strong backlash and editorials opposing the hidden rain tax.

- A western county decided to avoid stakeholder involvement in the process, only to start over from the beginning after two years of effort as the public caught on to what was happening and council decided to involve them.

The cost of appropriate due diligence is not insignificant but should be put in perspective. Experience has shown that, should a stormwater utility fail for whatever reason, it normally takes five to seven years for there to be a staff willingness and political forgetfulness to make another attempt. The opportunity cost of failure is then five to seven years’ revenue. The cost to do a thorough job in due diligence along the five tracks mentioned is rarely more than one to three months’ revenue, at the low end of the range for larger utilities.

For example, for a stormwater utility that raises $2 million per year, the opportunity cost of failure is $10 million to $14 million, while the cost to develop the utility in a comprehensive way is probably less than $450,000.

Additional benefits of appropriate due diligence on the front end include:

- More efficient long-term database maintenance, leading to lower costs and better customer service

- Better initial and long-term public knowledge and cooperation, leading to greater support and participation

- A funding rate structure that matches and meets program needs, both short-term and long-term, leading to stable, adequate funding for program needs

- A stormwater program that can meet both the capital and operations needs of the local community, leading to better services and ability to meet regulatory demands

Those communities that have cut corners in due diligence, even if the stormwater user fee should go forward, normally find themselves hampered in ability to manage the database, meet customer expectations, solve flooding problems, meet regulatory needs, and bend to meet changing program demands.

Summary

By this point in the TV CSI investigation, all the lab tests have taken scant minutes to perform by beautiful and competent people, the staff seems to have an encyclopedic knowledge of a vast range of arcane facts (“Why, yes, the jub-jub tree, which grows only in one Florida county, does excrete a substance that causes natural rubber on the soles of Nike shoes to turn yellow”), the crime has been solved neatly, the bad guys are hauled off to jail, and the music comes up to a shot of the fading south Florida sunset.

It’s not always so in the real world. No matter how skilled we are, how experienced we have become, how good the process is, and how much time and money we have to establish a stormwater utility the right way, something unexpected and unknown may happen and kill the whole thing. Its is not rocket science—it is harder. Rockets do not react emotionally, irrationally, and politically. We all have the scars to prove it.

Most places eventually realize and become willing to have a sound, comprehensive surface-water management program. They realize they cannot pay for it using current sources. That is, in fact, the bottom line in any discussion about our ability to improve stormwater management.

It is worth going for it, and doing it right, even if it does not go forward…this time. As stated in Reason #1, the cost of trying and failing may be high. But the cost of doing nothing is higher still. We have one chance to develop things right—to provide for safe and attractive neighborhoods, ecological balance, and clean water. If we mess it up, it will take decades and millions of dollars to fix it later. After 20 years of establishing stormwater utilities, I can now visit a town or county in which I played a small role in founding a utility and see a vibrant program and a proud staff. Flooding is solved, parks are built, water is cleaned, and development is being guided into greener and less impacting approaches. Stable, adequate, and equitable funding is the most effective best management practice ever invented and should be a good candidate for grant funding.

And, of course, our team looks knowingly into the setting Florida sun, walking in slow motion, as the warm breeze blows our hair, the music comes up, and the picture fades to black.

References

National Association of Flood and Stormwater Management Agencies (NAFSMA). 2006. Guidance Manual for Municipal Stormwater Utility Funding.

Reese, Andrew J. 2002. “Developing Technical Policy With Citizen Groups.” Stormwater 2 (3).

Acknowledgement

Special thanks to Hector Cyre, who formed this list with me over many beers and lots of Thai food.