To claim that San Francisco has some catching up to do to manage its stormwater “is fair,” says Karen Kubick, director of Wastewater Capital Improvement for the San Francisco Public Utilities Commission (SFPUC)

She adds, “It will take us another 15 years to catch up. Not since the 1970s has there been a big capital upgrade.”

San Francisco has eight distinct urban watersheds, five on the Bayside and three on the Westside. The city’s combined sewer system (CSS) has more than 1,000 miles of pipe, about one-third of which is more than 100 years old.

Officials at SFPUC and other municipal agencies know that replacing the aging infrastructure is critical. Another challenge they face is the seismic vulnerability of the CSS—it simply wasn’t built to withstand earthquakes.

As in many other cities, changes in weather patterns are bringing more severe and more frequent storms. All of that leads to more flooding and combined sewer overflows (CSOs).

The city’s three aging treatment plants handle 75 to 80 million gallons on a day without rain, and as much as 575 million gallons on a rainy day. That volume adds up to 40 billion gallons treated per year.

“Our treatment plants were designed in the 1940s and built in the 1950s,” says Kubick. “The newest plant, Oceanside, is 21 years old. They need seismic upgrades.”

When San Francisco’s CSS is overwhelmed by a major rain event, the runoff has nowhere to go except into San Francisco Bay or the Pacific Ocean. As is the situation with many other cities, San Francisco is playing catchup ball, using both gray and green infrastructure to manage its stormwater better.

Enter the Sewer System Improvement Program (SSIP). This ambitious program is a 20-year, $6 billion investment, of which $400 million has been designated for green infrastructure projects or portions of gray and green infrastructure projects.

One of the priorities of the SSIP is to address the aging Channel Force Main. Part of the Bayside Collections System, this major artery transports 64% of the wastewater from the Bayside to the Southeast Treatment Plant.

This important piece of infrastructure is a weak link on the Bayside because it is vulnerable to seismic damage. Channel Force Main has suffered several failures since the 1989 Loma Prieta earthquake.

The proposed solution is to add gravity tunnels, pump stations, and other gray infrastructure to supply the capacity that the Bayside CSS sector requires, now and in the future, should Channel Force Main malfunction. Construction would take several years and be finished in early 2023.

Phase one of the SSIP includes eight innovative green infrastructure projects, one in each of the city’s watersheds. Most are in either the construction or design phases.

“We’ll spend $57 million on these projects over the next two years,” says Kubick. “We’ll do monitoring on them for at least three years, maybe longer on some of them.”

The first part of the first green SSIP project is finished. Done in partnership with the city’s Metropolitan Transit Authority (MTA), it is located in The Wiggle neighborhood. This project includes rain gardens, bulb outs, and modified bike lanes. Construction on the second part of the project will begin this August.

A future green infrastructure project in the group of eight is daylighting of the historic Upper Yosemite Creek. Its purpose is to manage flows from 110 acres of McLaren Park. The creek will flow along the northern edge of McLaren Park from Yosemite Marsh through Louis Sutter Playground and along the southern edge of University Mound Reservoir. This green infrastructure project is the first creek daylighting project initiated by the city.

A channel in Yosemite Creek will convey stormwater and alleviate localized flooding.

Other benefits to San Francisco residents will be an enhanced natural habitat for relaxation and wildlife viewing plus educational opportunities for students. This creek project “will be a neat public asset,” says Kubick.

The San Francisco Recreation and Park Department is also involved, to suggest ways that the newly daylighted creek will add to existing parts of the park. Construction of the project is expected to take a year, with completion in spring 2017.

Other green infrastructure projects in SSIP’s initial group include the Mission and Valencia Green Gateway (rain gardens and permeable pavement plus enhanced pedestrian and bike pathways) and the Sunset Boulevard Greenway.

San Francisco’s famous Chinatown will get its own Green Alley project. Spofford and Ross alleys there will have rain gardens, permeable pavement, and some inviting community space.

Kubick says that installing these projects in public rights of way and public roadways is very challenging. “There are so many utility lines already there.”

Each project has its own particular challenges. “In Chinatown, for example, the streets are so narrow. There are ADA [Americans with Disabilities Act] issues and problems with fire escapes. For each installment, the fire department has to review it. Parking is at a premium, too,” she adds.

The overall design standard for the eight SSIP green infrastructure projects is to be able to handle a once-in-five-year, three-hour storm. “Some of them may vary from that,” says Kubick.

Cesar Chavez Streetscape Improvement Project

These green infrastructure projects have a good example to follow in the Cesar Chavez Streetscape Improvement Project. Completed about two years ago, this project involved a partnership between SFPUC and the San Francisco Department of Public Works (SFDPW). Green infrastructure was installed along a 1-mile corridor of the busy street.

The street was under construction for a long time, as sewer lines had to be replaced. That situation presented an opportunity for adding the green infrastructure, which is being monitored for performance. The project includes 14 feet of planted areas and 20 bioretention planters in select curb bulb outs.

San Francisco is not working under a consent decree from the Environmental Protection Agency. The impetus for adding green infrastructure has come from a realization of how costly replacing gray infrastructure is and what green infrastructure—properly designed and installed—can do for such a highly urbanized environment.

“San Francisco had gotten very impervious. Every drain spot had to be tied into the sewer system and rain was looked at as something to get rid of,” explains Kubick.

Now, looking at stormwater “as a resource” means a lot of change, for both SFPUC and other municipal workers, for contractors and developers, and for the general public. That sea change has required the hiring of new employees who are well versed in green infrastructure and training existing employees.

“We have to hire community experts, technical experts, people experienced in modeling and monitoring,” says Kubick. “It’s a different way for us to do design work.”

Rendering of The Wiggle neighborhood

She adds, “We’ve developed standards and specifications for our design because designing green infrastructure is new. Private firms do up to 35% of the design work. Then the city landscape architect takes over the final design. Then projects go out to bid.”

Because these stormwater projects are new to the people installing them, “we require contractors to go through a four-hour training course on green infrastructure,” she says.

Installing green infrastructure in streets and other public areas also means a lot of outreach and education to the taxpayers who pay for it.

“We have tens of meetings with neighborhood groups,” says Kubick. “We do four-hour workshops with different tables set up so people can learn about SSIP, about SFPUC, about green infrastructure.”

One reason SFPUC does extensive public outreach, she explains, is that “San Francisco is such a highly urbanized area. Loss of parking spaces, bike lanes, and handicap access are noticed. We want to ensure that we have public support. Prior to this, we built gray infrastructure. It was underground, so the public didn’t see it.”

Even with the new emphasis on green infrastructure, SFPUC is moving carefully. Kubick says, “What we’re really going after in San Francisco is performance-based green infrastructure. We want to remove stormwater from the streets and the sewer system.” To achieve that goal, “We’re being deliberate about site selection and pretesting,” she explains.

Along with its efforts to install more green infrastructure projects, SFPUC has given priority to two other stormwater-related programs. The improved version of the training course for contractors should be finished this summer.

“We’re doing an urban watershed assessment. We’re looking at soils and collection systems for each street in the city to see how we can manage stormwater better. We’ve taken the challenge out to the public through charrettes,” says Kubick.

SFPUC is also “updating plans to get a better idea of the roles and responsibilities for city staff in various departments,” she adds.

Kubick believes that the biggest challenge for green infrastructure is “to have a cross-sharing of responsibility so that all city departments include it in their budgets. It’s a new way of building things for everyone.”

She notes that SFPUC is hoping for some EPA grants in the future. The agency is looking at more public-private partnerships. “We want to do incentive grants.”

SFPUC’s own headquarters building deserves mention for its innovations. It is one of the first buildings in the nation with onsite treatment of gray and black water. All of the building’s water fixtures are rated as highly efficient.

An onsite wetland-based system called the “Living Machine” reclaims and treats all of the building’s wastewater. That supply is sufficient to satisfy 100% of the water demand for the building’s low-flow toilets and urinals. The Living Machine treats 5,000 gallons of wastewater per day. That number equates to a reduction per person of potable water consumption from 12 gallons to 5 gallons.

Planters inside and outside the building filter the building’s wastewater through a process similar to what happens in a natural wetland. Rainwater is harvested and used throughout the project for irrigation. The facility can store up to 250,000 gallons of water per year for use by the exterior irrigation systems.

The site can manage 100% of runoff from a once-a-year, 24-hour storm event.

Mint Plaza

On the private side, San Francisco has some outstanding green infrastructure projects that keep stormwater out of the city’s CSS. One of those projects is Mint Plaza, with design by CMG Landscape Architecture and engineering by Sherwood Design Engineers.

Several nationally registered historic warehouses and a decommissioned US Mint building adjoin the 18,000-square-foot plaza. Even though the site is a formal, urban area the buildings, plantings in the rain gardens, and the bright red chairs make the plaza a welcoming place. Nearby regional public transportation has helped attract residents and businesses.

Mint Plaza was completed in 2009. It has two rain gardens. The garden at the 5th Street edge of the plaza is planted with a coast live oak tree, Quercus agrifolia. Other plants include elk blue California gray rush (Juncus patens), island alum root (Heuchera maxima), small cape rush (Chondropetalum tectorum), and autumn gold maidenhair tree (Ginkgo biloba).

The other rain garden is located in the center-rear of the plaza. Some of the runoff flows into the rain gardens for onsite retention and bioremediation.

Scott Cataffa, principal at CMG Landscape Architecture, says that each rain garden measures 300 square feet, and the subsurface infiltration area is 700 square feet. For the gingko trees, the Silva Cell suspended paving system covers 800 square feet.

Additional stormwater runoff is collected in a slender slot drain connected to an underground distribution system, Infiltrator Systems Inc.’s High Capacity Chamber that slowly infiltrates this water into the sandy soils underlying the plaza surface.

John Leys, principal with Sherwood Design Engineers, says the biggest challenges to this project “were probably a couple of things. On the design process side we were working between different agencies to get final approval and permits. This was the first time in San Francisco for a lot of these things. SFPUC was breaking new ground in a city with a fairly conservative regulatory process.”

For dealing with the runoff, “we were trying to treat and infiltrate water in space that was constrained with all of these public utilities. We were within the right of way where we would impact subsurface [installations]. We had to do some tweaking and shifting to avoid a big steam pipe,” says Leys.

He adds, “We had to perc test to be sure the sand would infiltrate. We tried to enlarge it to get it to infiltrate as much water as possible.”

All of that pretesting proved a good idea. Leys notes, “It’s been installed for years and we haven’t seen any water leave the plaza.”

The project also exemplifies a successful private-public partnership. The public benefits, but very little public funding was needed. City funds comprised only $150,000 of the project’s $3.2 million capital budget.

Cataffa says CMG suggested to SFPUC that the firm and the public agency work together on a pilot project to manage urban stormwater. SFPUC agreed on the Mint Plaza project. After Mint Plaza proved to be effective at managing stormwater, SFPUC began requiring “all new city development that impacts more than 5,000 square feet of site area to meet volume-reduction goals.”

He adds, “We’re pleased that SFPUC can point to Mint Plaza as an exemplary BMP strategy.”

The developer, Martin Building Company, created a community facilities district that levied a 30-year special property tax on certain properties to provide the up-front funds for the design and construction of the project through tax-exempt bonds.

The developer also formed a nonprofit organization, Friends of Mint Plaza, to raise funds to manage ongoing maintenance and programming on the plaza. By scheduling events after work hours and on weekends, this organization makes sure that Mint Plaza remains in the public eye and is well used.

Mint Plaza has won several design awards, including the American Institute of Architects Small Firms, Great Projects 2008 Merit Award, the American Society of Landscape Architects-NCC General Design 2010 Award, and EPA’s 2010 Smart Growth Civic Spaces Award.

Davis Court

Davis Court

Another innovative stormwater project with engineering by Sherwood Design Engineers is Davis Court in downtown San Francisco. Royston Hanamoto Alley & Abey Landscape Architects provided landscape architecture design for the project, which was completed in 2010.

Davis Court is privately owned urban space between privately owned residential condominiums. For years, pedestrians and bicyclists have used it as a corridor for traveling to and from the downtown area to the waterfront properties. Cars, mostly from area residents, sometimes used the narrow space, too.

The goal of the project was to make it a more pedestrian-friendly site, a true woonerf, a Dutch term for a street used primarily by pedestrians and bicyclists and only secondarily by motorists.

“This was one of the first of these in the US,” says Leys. “You see these a lot more in Copenhagen and other parts of Europe.”

To achieve the project’s goal and manage runoff required creating a unique stormwater collection, conveyance, treatment, and groundwater infiltration system integrated into the tree-planting zones.

The first task was to deal with curbs that were 8 inches high. “We needed to bring the entire plaza to an even plane with no curbs. A lot of the community members are elderly and couldn’t manage high curbs,” explains Leys.

He adds, “We brought the whole street up so it crowned and drained to the edge. Then we put slot drains where the curbs had been. The slot drains were connected to eight rain gardens with street trees in planter areas. The rain gardens are not just cells, but sequentially connected below the surface.

Because trees need larger amounts of soil and more void space so more water can get to their roots, structural (organic) soil was added. Silva Cell tree planters were used.

Now all of the stormwater at Davis Court is infiltrated except for a portion at the far end that goes to the sewer system.

“The majority of the site captures, treats, and retains through infiltration onsite,” says Leys.

The most challenging part of the project was “getting the aesthetic to work with the grating and drains,” he notes. To that end special pavers—not permeable—were placed in a special pattern that didn’t allow for warping. Cutting strong lines and careful placement created slots to control the direction of the runoff.

“We cut out concrete where we needed to, to control the water and keep it at the surface and shallow. To get water into a rain garden, it has to be shallow,” explains Leys.

The design for placement of the paving was one-tenth of a foot contour. Leys says that is much more detailed than usual—10 times more than people typically use.

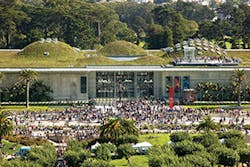

Green roof at the California Academy of Sciences

California Academy of Sciences

The presence of green roofs is another indication of the state of green infrastructure in a city. San Francisco has some impressive green roofs, but fewer than what might be expected.

The green roof above the California Academy of Sciences ranks with the most impressive green roofs anywhere. Designed by the landscape architecture firm SWA Group, the 197,000 square feet roof was completed in 2008.

SWA Group principal Lawrence Reed says that the project’s biggest challenge was “the ability to get a 6-inch layer of soil to conform to various slopes.” To manage successfully with slopes as steep as 60%, he says, “we built in a redundant support strategy.”

That strategy included a building 20-foot-square grid of columns. Then, Reed adds, “We created trenches of wrapped gabion rock. Inside the gabion we ran coated steel rebar through it and strapped those rebars together up and over a slope, like suspenders holding trousers.”

The plants had been grown offsite in 16-inch-square coir trays framed with bamboo. The strapped rebar “gave us a nice perch” for the trays of plants, he says.

The native plants growing on this green roof form the densest concentration of native wildflowers in San Francisco. The perennials are beach strawberry (Fragaria chiloensis), sea thrift (Armeria maritima), self-heal (Prunella vulgaris), and Pacific stonecrop (Sedum spathifolium). The annuals are coast California poppy (Eschscholzia californica), miniature lupine (Lupinus bicolor), goldfields

(Lasthenia californica), California plantain (Plantago erecta), and tidy tips (Layia platyglossa). The roof has grown into a thriving wildlife habitat.

Reed says that the green roof “is a science experiment along with an exhibit” and that since the green roof was installed members of the California Academy of Sciences have been overseeding and adding more plants.

“The 20- by 20-grid gave them nice control panels to do research,” he explains.

He says that the green roof has performed well infiltrating stormwater, but California’s drought and wind have stressed some plants on the western side. The academy has had to use the irrigation system there that was intended to be used only long enough to get the plants established.

“California is just beginning to talk about capturing water and reusing it for irrigation,” he notes.

SFPUC’s innovative building has a green roof, as does the city’s newest wastewater treatment plant, Oceanside. Other green roofs in San Francisco include those at 50 UN Plaza, the Matarozzi/Pelsinger Multi-Use Building, the Drew School, One South Van Ness, and the EcoCenter at Heron’s Head Park.

As for green infrastructure’s future in San Francisco, Reed says, “We’re seeing more and more of it.”

Leys says, “The city has done a lot to bring green infrastructure to the forefront. All new projects have to implement green infrastructure. Out of necessity, there’s a lot of collaboration and pretty much the whole Bay Area [is seeing] more green infrastructure.”

Kubick notes, “The public is really excited about it. We’re presented with more opportunities than what we can do.”

Noting the California drought and increased frequency and intensity of storm events, Cataffa says, “It’s more important than ever to sustainably manage our resources with green infrastructure. We are grateful to work in a city that recognizes this imperative and is working toward a more a sustainable future.”