In this case, a city needed to locate a site for a new 6-million-gallon water tank. Criteria included a parcel size of at least 3.7 acres to accommodate construction without excessive cut/fill or shoring requirements; preferably undeveloped land to avoid conflicts with constructed properties; elevation between 4,700 and 4,720 feet to match the intended pressure zone; and slopes less than 20% to ensure stability and access.

AGRC’s LiDAR data helped the city quickly narrow the list of eligible sites. Parcel data provided the shape and area, a DEM indicated the elevation, a derived slope raster gave the slope, and LiDAR intensity raster helped distinguish developed and undeveloped land. GIS tools streamlined the criteria evaluation and produced a summary of the eligible sites’ metrics. Engineers then examined aerial photography and other datasets to assess suitability before visiting short-listed sites in person.

In this case, a city needed to locate a site for a new 6-million-gallon water tank. Criteria included a parcel size of at least 3.7 acres to accommodate construction without excessive cut/fill or shoring requirements; preferably undeveloped land to avoid conflicts with constructed properties; elevation between 4,700 and 4,720 feet to match the intended pressure zone; and slopes less than 20% to ensure stability and access. AGRC’s LiDAR data helped the city quickly narrow the list of eligible sites. Parcel data provided the shape and area, a DEM indicated the elevation, a derived slope raster gave the slope, and LiDAR intensity raster helped distinguish developed and undeveloped land. GIS tools streamlined the criteria evaluation and produced a summary of the eligible sites’ metrics. Engineers then examined aerial photography and other datasets to assess suitability before visiting short-listed sites in person. [text_ad] When a tank site was chosen, initial planning and design relied on topography captured with LiDAR. With elevations recorded every 1.6 feet in a DEM, the site was characterized by over 70,000 points—detailed enough to substitute for expensive and time-consuming field topographic surveys in the early stages. Like Thompson’s application for stream projects, the DEM helped engineers prepare conceptual plans for the tank site and for new transmission lines to and from the tank, before proceeding with preliminary and final design. Water system models and inventories have benefited from AGRC’s LiDAR project. When hydraulic models and early system inventories were originally developed, some relied on intermittent or inconsistent data patched together from outdated maps or operators’ recollections. The new data—continuous and accurate along the Wasatch Front, where many large systems are located—allow engineers and utility crews to verify or update elevations attached to pipes, meters, tanks, and other features in computer models and inventories. Databases for drinking water, secondary water, stormwater, and wastewater systems have been updated with the new data to provide better accuracy and consistency. While reliable elevation data are welcome, other useful LiDAR products are available. Rick Kelson of Utah's Automated Geographic Reference Center (AGRC,) emphasizes how the data include more than just elevation. “The majority of people simply use the bare-earth DEMs to generate contours and topography,” he says. “But there is a wealth of information available in the first-return DSMs and point clouds.” LiDAR intensity, for example, which is collected with each LiDAR scan, has helped users identify impervious surfaces along the Wasatch Front. Intensity indicates the strength of the return pulse based on the reflectivity of the struck object. Roads, driveways, parking lots, buildings, and water bodies are easily distinguished from lawns, fields, and bare earth when examining an intensity raster. Such data may become the basis for assessing stormwater service fees based on impervious area. [caption id="attachment_35562" align="alignnone" width="300"]When a tank site was chosen, initial planning and design relied on topography captured with LiDAR. With elevations recorded every 1.6 feet in a DEM, the site was characterized by over 70,000 points—detailed enough to substitute for expensive and time-consuming field topographic surveys in the early stages. Like Thompson’s application for stream projects, the DEM helped engineers prepare conceptual plans for the tank site and for new transmission lines to and from the tank, before proceeding with preliminary and final design.

Water system models and inventories have benefited from AGRC’s LiDAR project. When hydraulic models and early system inventories were originally developed, some relied on intermittent or inconsistent data patched together from outdated maps or operators’ recollections. The new data—continuous and accurate along the Wasatch Front, where many large systems are located—allow engineers and utility crews to verify or update elevations attached to pipes, meters, tanks, and other features in computer models and inventories. Databases for drinking water, secondary water, stormwater, and wastewater systems have been updated with the new data to provide better accuracy and consistency.

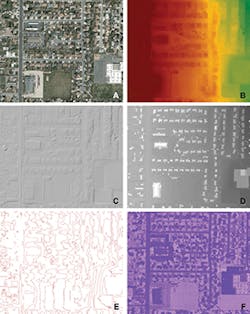

While reliable elevation data are welcome, other useful LiDAR products are available. Rick Kelson of Utah’s Automated Geographic Reference Center (AGRC,) emphasizes how the data include more than just elevation.

“The majority of people simply use the bare-earth DEMs to generate contours and topography,” he says. “But there is a wealth of information available in the first-return DSMs and point clouds.”

LiDAR intensity, for example, which is collected with each LiDAR scan, has helped users identify impervious surfaces along the Wasatch Front. Intensity indicates the strength of the return pulse based on the reflectivity of the struck object. Roads, driveways, parking lots, buildings, and water bodies are easily distinguished from lawns, fields, and bare earth when examining an intensity raster. Such data may become the basis for assessing stormwater service fees based on impervious area.

“LiDAR intensity is underutilized and can be used to quickly assess permeability or impermeability of an area,” adds Kelson.

Tarin Lewis, a project manager at Quantum Spatial (formerly Watershed Sciences Inc.) in Portland, OR, explains that investing in high-quality data is especially wise if the data can be used for multiple purposes. “LiDAR data has so many uses that when you’re planning a project it’s important to keep in mind what you may need the data for in the future,” she says. For instance, if certain modeling or analysis could be necessary later, “it may be worth collecting an even higher-resolution dataset right from the start to save time and costs.”

Casey Francis of Aero-Graphics in Salt Lake City confirmed that traditional LiDAR is being used in stormwater, floodplain, and watershed applications. LiDAR, he says, is “the most accurate, efficient, and cost-effective survey method for capturing and modeling complex hydrological systems.”

One limitation of standard LiDAR is its inability to penetrate a water surface to capture features beneath. However, a more specialized technology called bathymetric LiDAR operates at a different wavelength (in the green spectrum) and is able to seamlessly map the underlying bathymetry of river channels, lakes, and other shallow waters.

“This technology has huge implications for civil engineering, habitat analysis, and natural resource planning,” says Lewis. “We’re excited about the increased interest in this technology over the past year, and don’t expect it to slow down any time soon.”