Known for its involvement with banking and auto racing, Charlotte is one of the 10 fastest-growing cities in the US. The city’s 2014 estimated population is nearly 810,000.

Managing stormwater in Charlotte has multiple challenges, says Daryl Hammock, assistant stormwater division manager for the city. “We get a lot of rain—42 inches of rain a year,” he says. “Much of it happens very quickly, in thunderstorms. That’s the same amount of rain that Seattle gets, but ours comes suddenly.”

A second challenge is Charlotte’s clay soil. “We’re in the Piedmont region with clay soil that is slow to infiltrate and is vulnerable to erosion in urban settings,” he explains. “One of our biggest problems is stream stability. We’ve been removing stream buffers and adding a lot of impervious area.”

Charlotte’s high growth rate has led to what Hammock characterizes as “sprawling development. We’re not compact as other cities are. We have lots of stormwater drainage infrastructure per citizen, and that affects our fees and maintenance costs.”

And as if those challenges aren’t enough, he says, “Our biggest challenge is aging infrastructure.

We have a lot of our storm drainage system dating from the ’70s and ’80s, and it’s starting to fall apart at an increasing rate.”

Fortunately, Charlotte’s stormwater officials don’t have to work under the extra burdens some other cities find themselves carrying. Charlotte is not operating under a federal consent decree, and the city’s storm and sanitary sewer systems are entirely separate.

“We have some TMDLs [total maximum daily loads] as part of our permit, and we’re working on them,” says Hammock.

Charlotte and the surrounding county of Mecklenburg have a joint operation, Charlotte-Mecklenburg Storm Water Services (CMSWS). Funding includes a stormwater utility fee that has been in effect since 1993.

South Park Campus Watershed Enhancement Project

“Many of our water-quality projects are on parks or school property. We colocate when it is mutually beneficial for both entities,” says Hammock. One of those colocated stormwater projects is the CMS (Charlotte-Mecklenburg School) South Park Campus Watershed Enhancement Project. Begun at the request of nearby residents who were concerned about stormwater, this project was a joint venture between the school system and CMSWS.

The South Park Campus is home to Myers Park High School, Alexander Graham Middle School, and Selwyn Elementary School. The campus covers 71 acres.

Finished in 2013, this project was a retrofit. It was designed to treat runoff to improve water quality of Briar Creek, control peak flow, and provide science education for the students.

Nearby residents walk its trails, and waterfowl and other wildlife benefit from the added habitat.

Any retrofit project is more difficult than the same project would be if it had been done before buildings, streets, and other infrastructure were installed. At South Park, consideration had to be given to maintaining play areas and athletic fields, disturbing school operations as little as possible, and keeping options available for future construction.

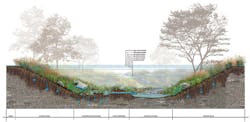

BMPs that would be the most cost effective were installed at five sites. They include two bioretention areas, an enhanced grass swale and chambered water elements, a wetland with inverted siphon, and a dry detention forebay and sand filter infiltration basin with interconnected step pool.

While the South Park project treats runoff from 36 acres of the campus, Hammock notes, “We’ll need hundreds of similar projects. We have a lot of impervious areas that were built without any stormwater controls.”

After a 0.77-inch rain

Linda Lake Drive

The Linda Lake Drive Regenerative Stormwater Conveyance Project is a creative green infrastructure project. It was the solution for a big problem: a gully that measured 230 feet long, 30 feet wide, and 25 feet deep at its largest points.

Runoff from 15 acres flowing through an outfall in a suburban neighborhood created safety concern, with massive erosion and pollution that flowed into a nearby tributary of Reedy Creek. Piping the runoff to Reedy Creek would not reduce pollutants or the volume that could worsen localized flooding.

After the gully was filled in with mulch and sand, a plunge pool was built directly below the outfall. Then a series of pools separated by weir grade controls was installed. The mulch and sand below the pools infiltrate and filter runoff.

Plunge pool at outfall

Monitoring to be done at the inlet and downstream weirs will show how well the project is working. The series of pools cascading downward add to the natural setting.

Several years ago, Hammock says, CMSWS began testing rain gardens and other nonproprietary measures. “We found that, when possible, regional strategies such as ponds, wetlands, and sand filters are cost-effective due to economies of scale.” He notes, “As regional opportunities become scarce, we will have to implement more green infrastructure devices into targeted watersheds.”

He adds, “Infiltration is a secondary goal to us. Our primarygoal is to remove pollutants. In clay soils it is very expensive to infiltrate. It’s a good idea, but we have to be cost effective.”

Looking Ahead

To serve its goal of improving water quality, CMSWS emphasizes stream rehabilitation and the protection and reestablishment of stream buffers. One way of acquiring funds for stream improvement projects is through the city’s innovative Stream and Wetlands Mitigation Bank.

“In the early 2000s we established a Stream and Wetlands Mitigation Bank for use by the city and Mecklenburg County government entities. Our agreement with the Army Corps of Engineers and the federal government requires mitigation for the unavoidable impacts of local government projects,” says Hammock.

“The city, county, and local government entities were paying money to a state fund, and the state was building restoration projects mostly outside of our watersheds. So we built stream projects and banked them so our government entities could purchase projects that help our watersheds,” he explains.

“We have rehabilitated about 14 miles of streams, with 9 more miles planned. We sell mitigation to city and county government entities, and the proceeds fund future projects performed by private sector contractors,” he notes.

Another forward-thinking stormwater program in Charlotte is the city’s asset management program. The program started about two years ago, and Hammock says this type of program is not very common in municipal stormwater departments.

Taking a proactive stance, CMSWS sends employees out to assess the condition of culverts and other parts of the stormwater drainage system. “We’ve always been very busy because of our call in system where citizens report stormwater and flooding problems. We’re responding to citizens’ calls, but there are also things we want to know about earlier,” says Hammock.

“When we go out and find a problem, we add it to our repair backlog. This approach adds to our workload now, but it should slow the growth of problems in 10 to 15 years. Then we won’t have culverts completely washing out” and causing more expensive problems, he explains.

Since 2008, Charlotte’s stormwater permit has required that stream buffers be protected during private and municipal building projects. Developers must also preserve trees. Hammock says that there were various earlier ordinances relating to stream buffers, but the 2008 regulation is “the most comprehensive. It widens buffers in some cases.”

He adds, “We tailor buffer widths to the adjacent water bodies. They’re driven by the sensitivity of the water that is being protected. The widest buffers are where endangered species are. We have narrower buffers in more urban areas.”

Open green space accessible to the public also helps improve water quality and infiltrate some rainfall. The Mecklenburg County Parks and Recreation Department has developed more than 35 miles of connecting greenways or trails.

As in many other cities, Charlotte residents are working to increase their city’s tree canopy. The goal set by the Charlotte city council is to have it reach 50% by 2050, which will require planting 500,000 more trees.

The Arbor Day Foundation, the American Forests Association, and EPA are among the national organizations that advocate trees in urban areas for stormwater management. Tree canopy holds some of the initial stage of a rainfall, thus lessening peak runoff volumes.

Soil that infiltrates poorly, rapid growth of impervious surface, and no limitation of building in floodplain areas are a recipe for flooding problems and are part of the city’s history. CMSWS has been working to reduce flooding and surface water issues and has developed innovative coping strategies over the years.

One of CMSWS’s strategies for dealing with flooding is its buyout program for property owners in floodplain areas. “Since 1999, we’ve removed over 700 families and businesses in 400 homes and buildings from the regional floodplain. We reverted these 160 acres of developed floodplain areas to green space, using federal and local funds,” says Hammock. “To date, we invested about $65 million and will avoid $300 million in flood losses.”

When the buildings have been cleared from these floodplain areas, CMSWS consults with the community and other agencies, such as the Department of Parks and Recreation, on how to best use the open space. Possible additions to the sites include restored wetlands, reforested areas, community gardens, and greenways. The greenways connect with other parts of a countywide trail system for public recreation.

The Chantilly Ecological Sanctuary at Briar Creek project is one example of how the floodplain buyouts have made residents safer, while also creating a community asset program. The project is currently being constructed on the site of the former 325-unit Cavalier and Doral apartment complexes, which were built in the 1960s, long before floodplain building restrictions went into effect. “Only a few inches of rain led to flooding in hundreds of apartments,” says Hammock.

In only nine years, residents of the two apartment complexes endured three floods and millions of dollars in damage when nearby Briar Creek flooded. Thirty-two apartment buildings were torn down between 2008 and 2010.

The $4.5 million project involves the restoration of 4,500 linear feet of channels of Briar Creek, Edwards Branch, and Chantilly Tributary and the construction of two water-quality control measures. Also included will be a greenway trail, educational signage, and 24 acres of open space and wetland habitat along Briar Creek. The project will be finished in fall 2017.

In recent years CMSWS has been able to take other proactive responses to flooding. The agency uses “future conditions” floodplains guidelines to ensure new development is reasonably safe from future flooding.

Mecklenburg County has an automated flood warning system with 140 rain/stage gauges that notifies emergency first responders. Residents now have a stronger incentive to buy flood insurance because of a 25% discount secured through FEMA’s Community Rating System Program.

Reflecting on managing stormwater in fast-growing Charlotte, Hammock says, “10 or 12 years ago we thought we had conquered our repair backlog, but one never really conquers [an ongoing] backlog, and our backlog has grown considerably since the early 2000s. Development was so aggressive in the last century.”

Now, he says, “Our most immediate challenge is to keep up with the pace of failing infrastructure. Fortunately our city council is working with us.”

To make Charlotte’s municipal funding stretch further, “we take a holistic approach. We look for flood reduction opportunities in water-quality projects and vice-versa. We do projects with multiple benefits whenever we can.”

Green roofs are showing up more and more in Charlotte. Green roofs above Mecklenburg County Courthouse and the Federal Reserve Bank of Richmond’s Charlotte Branch measure 6,100 square feet and 65,000 square feet, respectively.

The green roof at the Ritz-Carlton Hotel includes a chef’s garden and two beehives. Green roofs also top the Autobell Carwash, Discovery Place Museum, Carolinas Medical Center, Duke Energy Tower, ImaginOn, and the US Treasury Building.

Put an experienced landscape architect and civil engineer with vision to work designing projects and even the functional stormwater workings will enhance the natural beauty of the site.

That concept is clearly evident in two projects created by the Charlotte firm of LandDesign.

Little Sugar Creek Greenway

Little Sugar Creek runs for 15 miles from downtown Charlotte to the border with South Carolina. Like many streams in other American cities, the urban downtown section had been mostly paved over so the space could be used for parking. What was visible wasn’t much to see.

But since the Little Sugar Creek Greenway (LSCG) was finished in 2012, downtown Charlotte has an inviting natural area for people and wildlife with stormwater quality and quantity management features. The site is about 32 acres.

Two thousand linear feet of the creek were daylighted. Five hundred linear feet of stream were restored.

LandDesign’s director of Greenways, Parks, and Open Spaces, Beth Poovey, PLA, was lead designer for this project done for CMSWS and Charlotte’s Department of Parks and Recreation. Kevin Vogel, P.E., a civil engineer and partner with the firm, also worked on the LSCG.

“We were trying to go above and beyond with this project. We wanted to make a difference,” says Poovey.

Vogel says the project’s main challenge was “to incorporate all the requirements everyone wanted and the stormwater treatment where we could.”

“Space was one of the biggest constraints. We were trying to balance environmental benefits with people benefits, space for them to go along the walkways,” says Poovey.

Before construction, there was more paved surface. “With 70% more impervious area there was a lot more walking space,” she explains. The design reduced the space for people, so “we had to keep the funding for a pedestrian bridge that would keep the connection between neighborhoods.”

The project area “is not manicured, so there’s little opportunity along the greenway to see the creek. The pedestrian bridge allows people to see it,” she notes.

The walkway ranges in width from 8 to 18 feet. The average width is 12 feet.

“This creek is very flashy. It can flood 8 feet up in 15 minutes. The regular floor is about a foot deep, so it changes dramatically when we have a storm,” she says.

“We constructed two fairly large linear wetlands [approximately 35,000 square feet] to capture and treat a portion of the drainage area,” says Vogel. “We’re treating for phosphorus, nitrogen, and suspended solids before discharge into Little Sugar Creek.”

He adds, “The drainage we collect in the wetlands is stored and discharged through a small pipe that holds the first flush, to remove pollutants. For larger storm events there is a level spreader along the entire length of the wetlands.”

In the wetlands, high marsh plants installed were common rush, switch grass, red hibiscus and swamp hibiscus. Low marsh plants used were sweet flag, white water lily, pickerelweed, and softstem bulrush.

“We were concerned that during more intense rainfall that inundated the floodplain, the wetlands would be submerged, but they have held up well. It’s a good incorporation of stormwater BMPs into a floodplain while still allowing room for the greenway trail,” says Vogel.

More than 500 new trees were planted along the greenway. They included nuttall oak, a red oak species, which Poovey says has the ability to survive in both dry and wet conditions.

Other native plants at Little Sugar Creek Greenway include tag alder, Carolina rose, and Dewey blue switchgrass. Bioretention areas were included in the greenway, but permeable pavers were not.

“We shy away from permeable pavers because our soils have lots of clay. Using permeable pavers means you have to add in a subdrain to have them be viable,” explains Vogel.

“There would also be long-term maintenance, and the costs would be more,” adds Poovey.

Rainfall from the 28,370-square-foot roof of a nearby culinary school is collected and held for irrigation in a 30,000-gallon Darco fiberglass underground tank.

Summing up this innovative project, Poovey says, “At LandDesign our motto is ‘Creating places that matter.’ Elevating this creek that was so polluted to an amenity, making an environmental impact, and providing education all matter.”

Vogel says that the LandDesign team sees stormwater as “an opportunity, not just a problem to solve. There’s always that opportunity to enhance the value of the place.”

A National Headquarters

The national headquarters for Lowe’s Home Improvement stores is in the Charlotte suburb of Mooresville. LandDesign partner Dale Stewart, P.E., headed the team that worked on this remarkable project.

The office park buildings total 1.6 million square feet and earned LEED Gold certification. Several thousand Lowe’s employees work there.

The 275-acre Lowe’s campus is a model for corporate sustainability. Built in three phases, it was completed in 2014. West and Stem of Winston-Salem, NC, served as architects.

Stewart says that for their new headquarters campus, Lowe’s top executives were concerned with the impact the large development would have on the environment. They were equally concerned about the effect the campus would have on their employees’ lives and health. They saw the new campus as “an opportunity for employees to work and play onsite, with healthy eating in the cafeteria and a beautiful natural setting when they looked out the windows.”

He says, “The site was limited to only 50% being built on. We said, ‘Let’s preserve the right 50%.'” He notes that the location is just above Lake Norman, a protected watershed, and a tributary to the lake bisects the site.

“One of the things that is so appealing visually gives an opportunity for how we manage stormwater,” says Stewart. “We decided to build a lake in the center of the campus, and the buildings would surround it.”

Water features on the Lowe’s campus include a series of waterfalls, a smaller upper lake (1 acre), a larger lower lake (7 acres), and the stream that already existed. The cafeteria, topped by a five-story building, was built over the live stream.

Now, he says, “Lowe’s employees can sit in the cafeteria and look out and see the waterfalls and the stream. There’s a serenity because of the element of water. We’re always trying to find a unique way to capture water—a fountain, lake, bioretention garden—as an element of the occupants’ experience. It’s something we place a lot of value on.”

The larger central lake was created by impounding the stream. It functions as an irrigation reservoir and wildlife habitat, as well as for stormwater management. A 38-foot-high Class C high-hazard earthen dam, designed with Geoscience Group, controls water from the stream.

“We have an outlet structure for the dam and provide a detention element. We control downstream for volume,” explains Stewart. “For water quality we created two linear stormwater wetlands [measuring 1.6 acres], parallel to the lake.”

Hiking trails for employees to use during breaks and after work cross the campus and wooded areas and circle the lake. As they walk around the lake they see educational signage that explains how the stormwater is managed.

“These are legacy projects we’re proud of. They’re special places for people and we’ve been good stewards of the land, especially relating to water quality,” says LandDesign’s Aaron Shier, PLA, who also worked on these innovative projects.

Inspired by the Lowe’s campus, LandDesign has designed another environmently- and water-sensitive corporate campus, recently completed for LPL Corporation. This project, in Ft. Mill, SC, also has a high-hazard dam, a waterfall, and graywater reuse capability.