Dramatic reductions in worker accidents and injuries. Lower labor costs. Fewer Workers’ Compensation claims and lower insurance rates. Strong customer satisfaction and convenience. Fewer rodent and litter problems. Huge increases in recycling participation and tonnage. With so many benefits, why hasn’t automated collection become the norm in the United States?

In fact, even during the economic downturn of the past several years, automated collection has been making slow but steady inroads. While no comprehensive database exists, a Google search revealed dozens of cities, towns, and counties across America to have adopted automated collection since 2008 including West Hartford and the Borough of Naugatuck, CT; Northville Township, MA; Kuala County, HI; Henrico County, VA; Owasso, OK; Lakewood and Elyria, OH; Oshkosh, WI; and Cookeville, TN, among others.

When Northville Township, on the outskirts of Detroit, solicited bids for a new solid waste contract in 2010, it requested options for keeping the current manual collection method as well as bids to convert to an automated system. All bids favored automated collection, and the contract was awarded to a local company.

Carts, however, were a substantial cost. Don Weaver, Northville’s director of public services, determined that he could save significantly by purchasing the carts directly and negotiated a $754,000 loan from the sewer and water fund amortized over five years. Northville purchased 96-gallon carts for single-family homes and 64-gallon carts for condominiums. Two carts were provided to each customer: one for weekly refuse collection and one for biweekly recycling. The carts, which include radio frequency identification (RFID) tags to track activity, are guaranteed by the manufacturer for 10 years.

This arrangement allows Northville, with 7,200 residential customers, to maintain current service rates for the next two to three years. For refuse and recyclables alike, customers are allowed to bag excess and place it next to the cart, which is dumped, refilled by the driver, and then dumped again. Where customers exhibit a routine need to place out excess material, the township will provide an additional cart at no cost to the customer. Excess material putouts have been minimal.

Northville’s automated collection program was initiated in February 2011. Public education was vital during the rollout, as residents learned to cope with storage of the large containers. Single-family residents were given the opportunity to exchange their 96-gallon carts for 64-gallon carts. Three months into the program, Weaver is receiving very few complains. “Residents like the convenience and the reduction in litter on pickup days.” Weaver also pointed out that, since automating, recycling tonnage has increased by 50%. Previously, recyclables had been collected in 18-gallon open bins, often overflowing.

Republic Services has seen a strong and steady trend towards automated collection despite the current economic downturn. According to Mike Davis, vice president, 51% of Republic’s fleet is automated. He projects continued growth to 54% by the end of 2011 and 80% by 2016. Davis cites safety as a major plus: “Automated collection has resulted in significant safety benefit for employees. There has been a dramatic reduction in lower back and shoulder girdle injuries. In addition, workers are no longer exposed to oncoming traffic.”

Waste Management has also seen a slow but steady switchover to automation in the past three years, particularly in the Midwest and portions of the South and Northeast. (Many Western communities have already adopted automated collection.) The company has also seen growth in automation in areas that have gone to single-stream recycling because of significantly higher participation rates that can lead to higher diversion rates.

According to Ken Beaver, director of innovation with the Environmental Solutions Group, rear loaders outsold automated side loaders (ASLs) two to one 10 years ago; now it’s one to one, and he sees this trend accelerating as the economy improves. “Many fleets would rather buy automation and keep employment levels where they are. We’ve seen reductions in accidents, injuries, and Worker Compensation claims with automation. Plus, driving an ASL is a plum job; driver turnover is low so you get the return on investment in training.”

Barriers to Automation

Financing a switch to automated collection is still a major hurdle for municipalities, particularly those that handle sold waste services in-house. Mustering the political will to change a solid waste collection program, educating customers, and addressing logistical challenges are other major barriers.

Capital and maintenance costs– The initial capital investment in new automated trucks and rollout carts can be significant. The trucks themselves average about $250,000 each, and ASLs require more preventive maintenance than rear loaders. Carts can run about $60 apiece but are very durable.

Greensboro, NC, currently has a 34-truck fleet of 31-cubic-yard ASLs-Autocar cabs, 31 with Labrie bodies-used for refuse and recycling. Sheldon Smith, solid waste division manager, says the equipment is cost effective from a maintenance perspective and is operator friendly. He is on a seven-year lease cycle covering maintenance, insurance, and replacement. He acknowledged that equipment costs have risen significantly: Greensboro’s first ASLs cost $75,000-$100,000; the city is now paying $240,000 for each truck.

Kevin Watje, chief executive officer of Wayne Engineering, observes that over the past three years the economic situation has depressed the adoption of automation. “Despite the major gains in efficiency that could be achieved, many cities have backed off of planned purchases.” The ASL is a very sophisticated piece of equipment that requires a high level of maintenance and service, he says. “It’s inherently challenging to keep a piece of equipment running that performs 1,200 to 1,400 lifts a day and a packer that’s cycling as high as 3,600 cycles per day. The user/purchaser expects six to seven years of life from an ASL, but a rear loader lasts about 10 years and requires five to 10 times less maintenance.”

However, Frank Kennedy of Curotto-Can argues that, while some automated systems require more maintenance, those costs are offset by avoided expenses, including lower labor costs, fewer accidents, and better fuel economy.

The carts are also a big investment. Kennedy estimates cart costs at $60 per household plus assembly and distribution. Davis agrees that the carts are a significant cost but believes that longer-term contracts allow those costs to be amortized over a longer time frame.

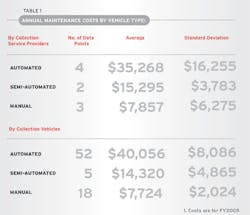

SWANA’s FY 2008 report, The Benchmarking of Residential Solid Waste Collection Services, corroborates the significantly higher maintenance costs for automated collection.

Labor Concerns– Expansion of automated collection has been limited in public agencies because of concerns about employee work force reductions, according to Don Ross, a project manager with Kessler Consulting. Ken Beaver agrees, observing that some municipalities are reluctant to automate because of citizen pushback about the possibility of laying off public sector employees

Municipal solid waste managers contacted for this story, however, indicate that in most cases, positions have been reduced primarily by attrition, or employees have been successfully retrained to become ASL drivers. At the same time, faced with major budgetary concerns, some municipalities are thinking about privatizing MSW services. Beaver observes that large private haulers have more flexibility to allocate automated trucks where needed than do individual local jurisdictions.

Resistance to Change– Republic’s Davis observes, “Automation takes off once one municipality in a region has taken the plunge.” Sharing success and best practices on a regional basis can be very helpful in educating municipal decision makers, particularly those that still practice twice-a-week manual collection. Some communities, however, remain reluctant to change the way they’ve always managed solid waste.

According to Wes Muir, director of corporate communications at Waste Management, some municipalities don’t want to give up unlimited trash pickups or require residents to fit all materials in a cart. And some communities find it difficult to accommodate two large carts, especially in duplex single-family homes or developments with small lots.

Factors Favoring Automation

Automated collection is taking off in municipalities where several key elements work in

Heil’s Starr System can easily maneuver in culde-

sacs and minimizes the need to back up.

tandem. A desire to improve worker safety is one motivator. Another is a solid analysis of the economic and logistical factors. A commitment to improving recycling performance is a third element driving automation. And critical to success is a commitment to undertake the political and communications challenges involved in making a transition from manual to automated collection.

Worker Safety a Major Plus

Industry data on traditional rear-loader operations indicate that a collection worker can lift more than 6 tons, on average, on a daily basis, resulting in a high rate of injury.

Charles Kamenides, operations manager of solid waste and recycling for the city of Longmont, CO, says that the biggest advantages to going fully automated is the reduction on Workers’ Compensation and the dramatic reduction in worked injuries. The city has righted staff size through attrition.

Longmont converted to automated refuse collection in 1999 and added single-stream recycling 10 years later. Located 40 miles north of Denver, the city serves 28,500 single-family residences, using Heil 7000 series split-container vehicles. Longmont purchases carts directly from manufacturers and offers 48- and 96-gallon containers at variable subscription rates that have not needed to be adjusted since the program began.

Watje agrees that automation dramatically reduces accidents and injuries to workers. “Rear loaders are inherently more dangerous-about 80% of all accidents within the refuse industry are associated with a crew of more than one person.”

Single-Stream Recycling

Don Ross indicates that “it is only since the advent of single-stream recycling in larger carts that once weekly automated collection has become a reality. One-one-one collection (refuse, recyclables, and yardwaste) is finally becoming the norm, which makes it economical to invest in automation, as the costs compete closely with manual collection. Add the value of a city-provided cart, and the proposition looks good.”

Kenney corroborates the close link between automation and recycling: “An issue that sometime gets lost in the automation debate has to do with recycling and the diversion goals that one seeks, and in some ways this is a more important component than any of the above. If we know that the only way to achieve a certain diversion rate is to recycle, and we know that the only way to reach the recycling goal is to provide single-stream collection, then the only type of service that can be provided is with a cart. If a cart is required for single-stream, then why can’t one be provided for trash, greenwaste, et cetera? This missing piece, then, is the collection vehicle that can best handle the cart system. Is the question really about “going automated?” Or is it really about attaining the virtuous goals of diversion? I think the higher road is the diversion rate that drives the path to going automated.”

According to the recycling trade press, recycling programs have prevailed despite the economic recession of the past several years. One indicator is the increase in the number of new material recycling facilities (MRFs) coming online to process single-stream commingled recyclables. According to Eileen Berenyi, Ph.D., president of Governmental Advisory Associates, there are 480 operational MRFs in the United States. Of these, almost half (42%) are single-stream or are taking single-stream materials. This compares with about 32% five years ago.

Kennedy agrees. “Resistance to making a service changes-even if automation clearly saves money and lowers injuries, et cetera-is more important than one might think. Changes in service are painful but worthwhile.

According to Berenyi, as of 2007, about 72 facilities have started up as single stream or converted to single-stream. Of these, 38% were in the Northeast, 33% in the South, 19% in the Midwest and 10% in the West. These data corroborate anecdotal information from industry contacts that single-stream collection of recyclables is growing in the Northeast and South, regions where automated collection is also slowing growing.

Automated recyclable collection is even working in tandem with subscription-based refuse collection. Maple Grove, MN, switched to single-stream recycling early in 2009 and is managing automated recycling collection in-house, while residents subscribe for automated refuse collection. This suburban community northwest of Minneapolis has realized a significant increase in participation rates and tonnage. Depending on their needs, households can choose among 32-, 68-, or 95-gallon Otto carts that are supplied by Allied Waste. Frank Kampel, recycling coordinator, says residents like the carts and the option of dropping off materials if they miss a collection or have very large items (such as a corrugated packaging from a new refrigerator).

Erik Schuck, general manager of Allied Waste Services of the Twin Cities (a Republic company), says most of his territory is subscription-based automated collection for both refuse and recycling. Schuck corroborates a significant increase in recycling rates with automated single-stream collection.

Innovative Technologies Address Logistical Barriers

Older, denser urban cities such as Boston, Philadelphia, and Baltimore still confront major barriers to automated collection, including narrow and congested streets and alleys. Rural routes are also hard to automate cost effectively. Equipment manufacturers, however, are meeting these challenges.

For example, Heil’s Starr System can easily maneuver in cul-de-sacs and minimizes the need to back up. It is also optimal for rural routes and for long hauls to recycling facilities and landfills, because full trailers can be detached, parked, and then pulled as tandems to minimize transportation costs.Wayne’s AutoCat is a mid-sized, fuel-efficient ASL designed for maneuvering in alleyways and cul-de-sacs. It handles 10 to 14 cubic yard bodies. A 600- to 800-pounds-per-yard compaction rating and 6-foot arm reach.

Equipment automation has also facilitated computerized routing. In 2007, Greensboro hired its first departmental GIS analyst who helped analyze and revamp the collection routes using RouteSmart software. This effort alone saved the city $1.1 million in reduced labor and equipment costs when Greensboro completed a collection route balance of the city in August 2010.

Careful Planning, Incremental Rollout, Customer Education

Beyond the economics and politics, careful program planning and a comprehensive customer information and education campaign are essential for a successful conversion to automated collection.

Greensboro implemented automatic refuse collection in 1984 and added single-stream automatic recycling collection 10 years later. The city directly serves 77,000 households (265,083 residents) “It took about seven years to fully transition,” says Smith. “We launched a widespread public information campaign and offered a second cart at a one-time reduced fee to homeowners worried about overflow issues during noncollection weeks and missing the second pickup.”

Abington Township, PA, understood the importance of good planning and public education when it launched its successful automated collection program in 2007. It took Abington seven years to move from a flat rate fee for refuse to the new automated hybrid variable rate for recycling and refuse collection system that includes Rehrig Pacific carts.

After investing considerable time and resources in research and analysis, the township piloted four collection methods ranging from fully automated to traditional rear-loaders. It also tweaked schedules and surveyed customers during the pilots.

Once the optimal collection method was identified, Abington embarked on a comprehensive customer education campaign and incrementally rolled out the new program in order to thoroughly educate each participant and quickly address questions and logistical problems.

Abington held 24 town meetings, made presentations at libraries, luncheons, and civic groups, conducted several direct mailings, published a quarterly newsletter, and advertised the new program on the township’s website and in local news outlets.

The program has exceeded all expectations for recycling volume increases and decreases in trash tonnages. The diversion rate went from 42% at the start of the program in January 2007, to 57% one year later. As an added bonus, the jurisdiction was able to reduce service costs to residents.

“It was a lot of work, but it was worth it,” says Ed Micciolo, public works director. “Automation gave us a way to increase collection efficiencies and save big on manpower. The program has been embraced by the residents of the township, new and old. They absolutely love it and work very hard to help us control costs so they can reap the benefits. We have been able to reduce their costs every year since the programs inception. Our recycling diversion rate has continued to increase and our program has become a model for other municipalities to follow.”

In 2009, SWANA recognized Abington’s program with a Gold Excellence in Collection Systems Award.

Kevin Watje also emphasizes the importance of a sequenced, well-planned rollout that allows for fine-tuning to address customer concerns, and stresses the importance of a well-orchestrated customer education campaign. “Aside from the economics, the biggest challenge faced by municipalities in converting to automated collection is orchestrating behavior change by residential customers.”

The city of Toledo, OH, learned these lessons the hard way. In an attempt to save money, in 2009 the city council invested $22 million on new automated trucks and bins and eliminated 70 trash collector jobs. At the same time, city officials promised residents there would be no change in service or fees. As reported in the December 31, 2010, issue of The Wall Street Journal, Toledo had to abandon this conversion to automated collection because of many citizen complaints and logistical problems. Residents had been accustomed to unlimited pickups but were not told how to handle oversize or bulky items that would not fit into the 96-gallon bins. Many setouts were not positioned properly for automated pickup. Toledo had to hire eight telephone operators just to field complaints and ended up deploying its old rear-loaders to run along with the new trucks, erasing any anticipated cost savings.

In early 2011, Lucas County assumed responsibility for Toledo’s solid waste services. The county solicited bids for private service and a contract was being finalized as of June. The new contractor will purchase Toledo’s Labrie Autocar trucks and Lucas County will take possession of the Toter carts. According to Edward Moore, Toledo’s director of public service, the city is in the process of placing laid-off collectors in other city jobs and are also hoping to place some of them with the new contractor.