“If there is magic on this planet, it is contained in water.” –Loran Eisley

Introduction

Prior to reservoirs and the extraction of groundwater, the availability of fresh water greatly influenced the movement of human populations within ancient Utah. Located within the geographical boundaries of the Great Basin, Utah’s early indigenous people lives were intricately connected to fresh water sources. While tribal boundaries were often determined by waterways, the appropriation or diversion of water resources was not a major concern, as their culture and values did not require laws for water use.

Water laws and regulations were later instigated by the Anglo-European settlers. After arriving into the valleys that sloped westward along the Wasatch mountain range, they diverted water from a creek in the Salt Lake Valley for their first crops. Eventually, Utah’s water resources were appropriated by legislation, and the simple canals morphed into a complex system of delivery, storage systems, and treatment facilities. More recently, economics and growth have influenced the development of additional legislation that includes water conserving ethics and regulations. This legislation was initiated primarily to ensure the future availability and safety of Utah’s water. Since water conserving legislation passed in 1998, several house bills and public outreach programs have been adopted by water conservancy districts and municipalities. Their main goal has been, “Slow the Flow of H2O.”

The Colorado River: A Liquid Asset

A vital, liquid asset that has changed the landscapes of Utah and other western states is the Colorado River. Critically important to seven western states, indigenous aboriginal tribes, and Mexico, it is considered to be the most regulated river in the world (Anderson 2002). Its headwaters originate within the peaks of the Rocky Mountain range in Colorado. However, before ending its flow into the Gulf of California, it provides water for municipalities, industry, agriculture, and hydroelectric power for cities.

Four of the seven upper and lower Colorado River Basin states are among the fastest-growing in the nation. Ranked by growth, they include: (1) Nevada, (2) Arizona, (3) Colorado, and (4) Utah. Utah, the second-driest state in the continental US, lies within the lower and upper Colorado River Basins. In 2000, diversions from the upper Colorado River totaled 953,000 acre-feet of water that was diverted at specific tributaries throughout the state. A majority of Utah’s diversions from the Colorado occur from the Duchesne River system in the Uintah Basin. This water is then transported to communities along the Wasatch Front through the federally funded Central Utah Project (CUP). Utah has rights to an additional 200,000 acre-feet per year of water that is calculated into its future water budget. Within the lower Colorado River Basin, the currently unused water is calculated to serve future populations expected to increase at a rate of 2.96% for the next 20 years. However, growth rates for the part of the state located in the upper basin are projected to be only 1.74% (Anderson 2002). In 1998, recognizing that increases in population within both upper and lower basins could equate to water consumption in excess of supply, the state legislature passed House Bill (HB) 418. In 2004, an amendment was passed (HB 71) that strengthened and refined certain guidelines of the original legislation.

House Bill 418: Considering Utah’s Water Future

Prior to the passing of HB 418, several communities were practicing water conservation measures that included universal metering, watershed protection, and had adopted water conserving rates for their culinary water supplies. HB 418 was written in response to the Utah Division of Water Resources, Division of Water Rights and a Utah state government subcommittee (the Governor’s Water Conservation Team) that recognized the importance of implementing statewide best management practices (BMPs) that would reduce water use, while increasing water awareness. Moreover, the language of HB 418 preamble was one of cooperation, rather than strongly regulatory: “…an act relating to water and irrigation; requiring water conservancy districts and water retailers to prepare and adopt or update a water conservation plan and file it with the Division of Water Resources; and requiring the Board of Water Resources to study the plans and make recommendations.”

Required to submit their plans by April 1, 1999, Utah’s water retailers, municipalities, and water conservancy districts serving more than 500 connections responded in varying levels of detail. While the requirements of HB 418 were similar to those required by Regional Drinking Water Facilities Plan initiative conducted in Utah to meet the federally mandated 1996 Federal Safe Drinking Water Act, HB 418 was comprised of 10 specific measurable guidelines:

- The installation and use of water efficient fixtures and appliances, including toilets, shower fixtures, and faucets

- Residential and commercial landscapes and irrigation that require less water to maintain

- More water efficient industrial and commercial processes involving the use of water

- Water reuse systems, both potable and not potable

- Distribution system leak repair

- Dissemination of public information regarding more efficient use of water, including public education programs, customer water use audits, and water-saving demonstrations

- Water rate structures designed to encourage more efficient use of water

- Statutes, ordinances, codes, or regulations designed to encourage more efficient use of water by means such as water efficient fixtures and landscapes

- Incentives to implement water efficient techniques, including rebates to water users to encourage the implementation of more water efficient measures

- Other measures designed to conserve water

Drought Cycles

While state models allocate for projected depletions based on historical evaporation rates from reservoirs, the values do not include adjustments for increased temperatures associated with global warming. The most recent drought cycle in Utah (2000–2007) impressed municipalities and water retailers on the necessity of having a viable drought contingency plan. During the evaluation of the conservation plans submitted for review from 1998 to 2008, the majority of the municipalities included severe drought contingency plans as a conservation “Best Management Plan.”

Many municipalities had the foresight to implement “increasing block” rate structures, concluding that they promoted conservation, while ensuring that municipalities had adequate funds for operations and maintenance. North Logan mayor, Val Potter, observed on the interrelation between water pricing, drought preparedness, and conservation.

“The drought got our attention! Wells are drawn down, pumping costs have increased, and the city is facing the expense of developing new storage and water,” says Potter. “We will need to conserve even after the drought. Pricing water for conservation is our best tool.”

As the plans were evaluated for thoroughness and conservation measurability by Utah Division of Water Resources conservation staff, additional factors were considered: (1) municipality size and (2) the resources available for water conservation project development. Awareness about the importance of water conservation plans varied from progressive and detailed, to brief statements about how water conservation practices were only necessary during times of drought.

Salt Lake City, with the largest population centers in Utah, considered the definition and scope of water conservation. “Water conservation is a set of strategies for reducing the volume of water withdrawn from a water supply source, for reducing the loss or waste of water, for maintaining or improving efficiency in the use of water, for increasing the recycling and reuse of water, and for preventing the pollution of water. . . . Every person, animal, and plant which resides within, works, or passes through our community benefits from water conservation. . . .”

While population and the complexity of the Salt Lake City water system contributed to the thoroughness of their conservation plan, many smaller municipalities also included rate incentive pricing and moderately detailed water conservation plans.

Evaluating the Plans

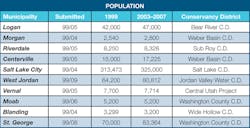

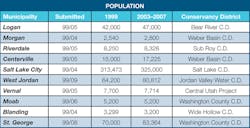

The municipalities chosen for review spanned the entire state, from Logan City located in the northern panhandle of Utah to Blanding City, nestled within the red-rock landscapes of the four-corner area in the south. Tourism, particularly in the southern portion of the state, contributes to seasonal peak water use. Those most affected by these seasonal fluctuations include Blanding, Moab, and St. George. Many of the cities also receive water from conservancy districts, in addition to their own developments. As stated within HB 418, all water entities were responsible for submitting water conservation plans, and, while this study has focused upon municipalities, their conservancy districts are also included. (See Figure 2.)

The major water conservancy districts are Jordan Valley Water Conservancy District, Weber Basin Water Conservancy District, Central Utah Water Conservancy District, and Washington County Water Conservancy District. Metropolitan Water District of Salt Lake City (SLC) and Sandy is not a conservancy district, but is a major wholesale water supplier to SLC and Sandy. There are also 19 additional water conservancy districts located throughout the state.

One of the primary roles of the conservancy districts is to assist their customer agencies in reaching the conservation goals they have set. For example: Jordan Valley Water Conservancy District (JVWCD) could never reach its goal of 25% reduction in water deliveries by 2025 unless all their customer agencies were striving to meet an identical goal. One incentive is water conservation grants. JVWCD provides $50,000 grants to each of its customer cities and districts. To receive the grant, a customer agency must illustrate quantifiable conservation measures that will facilitate the conservancy district reaching their conservation goals. West Jordan City (WJC) is a customer municipality of JVWCD. With a similar water conserving vision to the conservancy district, they have many exceptional water conserving programs they have developed from water conservation grants.

Measuring Change

The analysis of the water conservation plans submitted from 1999 to 2009, focused upon the implementation of the water conservation guidelines listed in both HB 418, and HB 71. In addition, a ranking system of “Currently in Use“, and “Not in Use“, was designated to both indoor and outdoor water conserving features. From the total number of municipalities that were evaluated, a percentage was established for each water conserving feature studied, and all data represents a total implementation, rather than an evaluation of each individual municipality.

Data collected from the submitted plans of HB 418 (1999) supplied a portrait of a statewide need to increase measurable water conserving guidelines. From the 10 suggested practices outlined within HB 418 only two water conserving practices, water metering for culinary water sources and mulching programs, were implemented by 50% of the selected cities and conservancy districts. In many instances, the submitted water conservation plans lacked reference to a particular guideline. (See Figures 3 and 4.)

Almost a decade later, HB 71 was enacted by the state. Municipalities and conservancy districts were required to reevaluate and resubmit their water conservation plans. Many municipalities, particularly those located within dense urban centers began to implement landscape rebates. Furthermore, the economics of water was considered, as several municipalities included changes in their water rate structures. Complimentary water audits created more partnerships between conservancy districts and provided an environment where “Community Conservation Groups” could flourish. Additional water conservation measures, including water reuse in the landscape and water metering for secondary water, saw an increase, though it still ranked below 50%.

Additional measures within HB 71 were included into the new plans. Several conservancy districts now had demonstration water conservation landscapes for area citizens and businesses to glean inspiration from, and over 60% had measurable results from their water education programs. Other successful measures included large-user water conservation programs for industry, municipal parks, and byways. West Jordan illustrated the estimated costs of water savings of their conservation programs and the associated costs per acre-foot. (See Figure 5.)

Rainwater Harvesting: A Popular Diversion

Recent legislation has recently added another dimension to water conservation efforts: rainwater harvesting. While the harvesting of rainwater is an ancient worldwide practice dating back to circa 1,500 B.C. (Hicks 2008), individuals have been unable to practice it, due to the state of Utah’s established water laws that follow the Doctrine of Prior Appropriation. The major tenants of the law are “First in time is first in right“, and “Use it or lose it.” During the early-anglo settlement, the right to use water was simply established by diverting the water from its primary source and then applying it for a beneficial use.

Consequently, the prior interpretation of rainwater harvesting meant that water was being removed from use downstream and appeared to contradict the “First in time, first in right“ doctrine. However, Senate Bill 128 is representative with how individuals view water in Utah and may promote greater water stewardship. While the amount of water that can be harvested is only 2,500 gallons in an underground container or 55 gallons in two aboveground containers/parcel (lot), it may facilitate increased wise water use applications of nonpotable water in landscape and toilet flushing. Particularly, when rainwater harvesting contributes positively to the equation, that describes monthly conservation practices: Supply > Demand (Kinkade-Levario 2007).

The Ultimate Partnership: Pricing and Conservation

HB 418 forges a link between water rates and conservation with the statement that, “Water conservation plans may include information regarding: (among other things) water rate structures designed to encourage more efficient use of water.” The latest document produced by the Utah Division of Water Resources (UDWR) in its State Water Planning Program, titled “The Jordan River Basin Plan” (2010), points out the major difficulty in setting water rates for conservation in Utah: Water is cheap. The average cost per 1,000 gallons of water in the Jordan River Basin, where most of the people live, is just $1.60. The state average is $1.15, compared to the national average of $2.50.

A widespread custom used in setting water rates is to set the price of water at a level where revenues equal the cost of delivery. To stay true to this cost of service, principle cities and districts avoid increasing the price of water to incentivize customers to achieve their conservation goals. Instead, some utilities have moved into some innovative conservation rate structures. Salt Lake City, for example, adopted a seasonal rate structure, as have five other major water suppliers in Salt Lake County. Some suppliers have added an increasing block feature to their summer rate.

A somewhat-new form of rate structure that is slowly gaining popularity sets a water budget or allocation for each customer in the residential, commercial, or other customer classes. No water providers in Utah have implemented this as of yet, but one major conservancy districts and one improvement district are taking a serious look. This water budget rate structure combines improved education on an enhanced water bill with tough overage charges for water used in excess of the water budget. With this one, the utility is responsible for deciding what amount of water constitutes efficient use for each customer. The customer is responsible for using water appropriately or paying a much higher price for the wasted water. In some cases, the extra revenue from the higher rates is used to fund conservation programs targeted toward helping those who are using excessive amounts.

Utah’s most popular conservation rate structure is the increasing block rate with 42% of the drinking water systems using it. As also with the other rate structures mentioned, a base fee ranging from $2.88 to a high of $36 is applied for each customer, and often, no water is granted for this fee (UDWR 2010). An increasing commodity charge is then set for each succeeding price block.

Conclusion: Conservation’s Bottom Line

Municipalities of all population sizes implemented many proactive and measurable additions into their water conservation plans. Several larger municipalities had exemplary water conservation plans that were both quantifiable and visionary. WJC is one example of successfully implementing comprehensive BMPs. Since HB 418, their per capita water use has decreased from 227 gallons per capita per day (gpcpd) to 193 gpcpd. These values reflect a 15% decrease in use from 2000.