Stormwater Management and Water Conservation Education

Stormwater utility managers and their advisory boards often face an uphill battle when communicating to their constituents the importance of stormwater management planning for their communities. Many utilities employ a variety of media outreach activities on TV, radio, and social networking. Other common activities include stream cleanup days, participation in local fairs, and presentations at service clubs and other community organizations. Even with these efforts, however, the challenge of grabbing the interest of both adults and children remains. Only when a storm floods an area or creates other localized stormwater-related issues do most adults suddenly want to know more about what their community is doing to control stormwater. In such moments of crisis, the question always becomes why communities have not done more to solve such flooding matters, rather than how different stakeholders can come together to discuss stormwater issues before the deluge.

Given these realities, a different avenue of outreach—reaching young people and their families through local schools and teachers—is garnering considerable interest. Such programs may include technical assistance to teachers and school officials to educate them on stormwater issues as well as the development and presentation of resource materials that allow teachers to share stormwater information with their students in a way that excites and engages them.

The outreach approach borrows from the solid waste field, at the dawn of the US “recycling movement” in the late 1970s and early ’80s. At that time, many experts in solid waste decided that the best way to reach homes to encourage recycling was to educate kids in public school programs about the benefits of recycling. The children took the message home to their parents and told them to recycle—and stepped in when they saw mom or dad throw away an item that could instead have been recycled. The approach seemed to work: An Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) target of reducing solid waste by 25% through recycling was met by the end of the 1990s. A study published in the Journal of Biological Education (Evans et al. 1996) confirmed that more parents recycled paper, plastics, and aluminum after their children took part in an environmental education program than they did before it.

As this article describes, the Bozeman Stormwater Division decided to emulate that outreach approach by reaching out to area families through the public schools. Bozeman is a rapidly growing college town of approximately 45,000 people in southwestern Montana. In this setting, a pilot partnership between the city of Bozeman and the Project WET Foundation—a global water education nonprofit headquartered in Bozeman—has significantly increased public awareness of both stormwater management and water conservation by targeting young people with interactive, science-based activities about stormwater.

Called the Bozeman Water Conservation and Stormwater Management program, the partnership has reached 554 students in Bozeman’s public elementary and middle schools during its first two years. Eight teachers in six different Bozeman-area schools piloted the program in fourth, fifth, and sixth grades. Pre- and post-assessments showed significant gains in knowledge about Bozeman’s local watershed as well as the concepts of stormwater management and water conservation: Over the two years of the pilot program, students’ scores from the pre- to the post-assessment improved by an average of 120%.

This article describes the context of the program’s development, its impact on students, the future of the program, and, most critically, the lessons learned that can be applied in other stormwater programs across the United States.

Background

Bozeman and Its Watershed. Known as a destination for outdoor recreation and as home to Montana State University, Bozeman has a vibrant economy and a growth rate far above the national average. Its residents take full advantage of the town’s mountain setting to ski, fly-fish, hike, and otherwise engage with nature. That work-to-play attitude carries over into a strong public recognition of the need to protect natural resources, including water.

Even with strong conservation attitudes from its residents, Bozeman faces considerable challenges as it continues to grow. Drinking water demand is expected to exceed available supply within 20 years, with diverse water-user groups including existing and new Bozeman residents, sprawling real estate development, agriculture, and conservation groups jockeying for a limited supply. In addition, the growth of population and business has created greater impacts on local waterways from urban runoff. Developing the city’s infrastructure—already stressed from a decade of rapid expansion—will require “out-of-the-box” ideas to enable the community to move forward sustainably.

As Bozeman is a high-desert town in the Rocky Mountains, its water supply is affected by shifting precipitation patterns. Snowpack makes up 80% of the city’s drinking water supply and is also responsible for recharging and feeding the pristine, low-volume rivers in the area. These rivers are greatly influenced by urban stormwater, agricultural runoff, and seasonal flow fluctuation, and as climate changes, more moisture may come in the form of rain rather than snow. Situated at the headwaters of the Missouri River Basin, Bozeman has an added responsibility to manage water resources wisely. City of Bozeman officials are well aware of their need to be conscious of impacts to downstream users.

“Bozeman’s watershed enjoys a water supply of high quality—but water managers must also deal with the perpetual issue of an insufficient quantity of water,” explains Lain Leoniak, the city’s water conservation specialist. “Reliant on snowpack and a variety of surface water supplies, the area is semi-arid, receiving some 16 inches of rain per year on average and making it vulnerable to impacts from drought. As a headwaters area, Bozeman cannot look upstream to find additional water, and the watershed is closed to new appropriations. Given these realities, the city of Bozeman recognized the value of educating future water customers about the true value of their water resource and the impact that stormwater may have on that resource as the community grows.”

Program Partners. Partners include the Bozeman Stormwater Division, the Bozeman Water Conservation Division, and the Project WET Foundation.

The City of Bozeman Stormwater Division and the City of Bozeman Water Conservation Division. The overall outreach strategy that both the Stormwater Division and the Water Conservation Division use is based on four pillars:

- educate those unaware of local water-supply and -quality issues

- inspire a cultural and behavioral change through positive interactions and incentives

- implement data-driven, solution-based programs

- engage targeted audiences through trainings, workshops, and media

Providing information and resources that encourage the community to use water efficiently—including future generations—is a major reason that the city of Bozeman sought to integrate water education into its work.

Fully funded and staffed for less than a year, the new Stormwater Division seeks to improve river health, ensure public safety, and exceed regulatory requirements.

Bozeman’s stormwater dumps directly into heavily utilized waterways known for their world-class fishing and recreational opportunities. Currently, the local community is relatively unaware of stormwater-related issues and their impact on the places city residents and visiting tourists treasure. From its inception, the Stormwater Division has taken an education- and solutions-based approach to program development, considering the extent of change required by the community to achieve programmatic goals. One central tenet of the division is never to present a problem to the community without having three solutions ready to go, and the partnership developed with Project WET represents one such solution.

The city is a Phase II MS4 permit holder required to implement best management practices designed to protect local rivers from the adverse impacts of polluted stormwater. The Stormwater Division is responsible for a variety of initiatives and programs, including water sampling, construction site management, infrastructure maintenance, project management, pollution response, and public education. City leadership takes a proactive approach to local stormwater issues, allocating more than $12 million dollars toward treatment, infrastructure, and operational investments in the next 10 years.

Within the Water Conservation Division, the goal is to protect and enhance Bozeman’s water resources to ensure a reliable water supply for the future to accommodate population growth, emergency response to drought, and long-term drought mitigation. To do that, the division works to establish and strengthen the community’s water conservation ethic through outreach, educating community members on the state of Bozeman’s water resources with an emphasis on why it is important to conserve water.

In 2013, the City Commission adopted an Integrated Water Resources Plan calling for approximately 60% of Bozeman’s future water supplies to come from demand-side management through conservation. Given Bozeman’s semi-arid climate, susceptibility to drought, and growing population, conservation represents a far less expensive option than traditional water infrastructure projects do, and it allows all water users to make a difference.

Alongside an incentive-based consumer rebate program, the Water Conservation Division has focused on educating the community about the environmental benefits of conservation, including the nexus to water quality, improved aquatic habitat, and support for fish and wildlife, especially in light of Bozeman’s economic reliance on the outdoor recreation and tourism industries.

The Project WET Foundation. A 501(c)(3) nonprofit organization, the Project WET Foundation (WET stands for Water Education for Teachers) develops and delivers water resources education for people of all ages, with an emphasis on reaching children through school and community educators. Although the foundation has been headquartered in Bozeman since 1989, Project WET’s reach extends far beyond Montana. Through its network of implementing partners, Project WET is active in all 50 US states and more than 70 countries.

The cornerstone of Project WET is its methodology of teaching about water resources through hands-on, investigative, easy-to-use “activities”—detailed, easy-to-follow lesson plans. Project WET activities are

- Accurate and science-based: Content experts review the information, and educators and students field-test the materials.

- Interactive: Engaging students through questioning and other inquiry-based strategies, educators involve students in hands-on lessons and encourage them to take responsibility for their own learning by seeking answers to real-world problems, playing games to explore scientific concepts, reflecting, debating, and sharing by creating songs, stories, and dramas.

- Multisensory: Full-body activities engage the senses, which research shows enhances learning.

- Adaptable: Project WET activities can be taught and performed indoors and outdoors, in a variety of settings with a range of group sizes.

- Contemporary, incorporating technology and 21st-century skills: In most activities, students work in small, collaborative groups. Many activities engage students in higher-level thinking skills, requiring them to analyze, interpret, apply information (problem-solving, decision-making, and planning), evaluate, and present.

- Cross-cultural: Materials prepare students for participation in a global economy, in which an understanding of water resources will be critical.

- Relevant: Educators are encouraged to localize activities to give them relevance.

- Solution-oriented: Project WET believes in linking awareness and education to action and solutions through its Action Education initiative.

- Measurable: Project WET activities provide simple assessment tools to measure student learning.

Development of the Partnership. In the course of garnering community support for a proposed Stormwater Division, city of Bozeman staff members visited dozens of organizations, agencies, classrooms, and civic groups to present the case for the new division. One organization on the list was the Project WET Foundation. In that presentation on Project WET, stormwater program coordinator Kyle Mehrens learned more about what Project WET did and saw the potential to work together. Recognizing the nexus between stormwater and water conservation, the Water Conservation Division was brought into the discussion soon thereafter. The two city divisions and Project WET made the decision to partner to share information and resources and provide mutual support.

Project WET developed a pilot proposal, which then had to go through the city’s approval process, ending at the City Commission. As very little competition exists for the type of work Project WET does, the process was straightforward. The city’s leadership decided to support the partnership, which it saw as a relatively small investment of time and money when compared to the total audience reached and the chances of the program’s long-term success.

How the Program Evolved

Methodology. After gaining approval from the City Commission and consulting with city officials, Project WET began work on the three main elements of the Bozeman Stormwater Management and Water Conservation program:

- customizing five Project WET lesson plans for teachers to fit the city of Bozeman’s priority watershed, conservation, and stormwater topics

- creating a digital publication containing these activities

- training educators to use the program

- implementing program in three classrooms at the upper elementary and middle school level

While Project WET has extensive experience developing customized water resources education solutions around the world, direct work in its “hometown” of Bozeman has been limited. Project WET therefore asked the Montana Watercourse (MTWC)—Project WET’s state partner in Montana, responsible for organizing and implementing Project WET water education training around the state—to take the lead on the teacher training component of the program. Housed at Montana State University, MTWC provides water education to Montanans statewide through programs, workshops, publications, and water assessment tools.

Simultaneously with the curriculum development, Project WET and MTWC began the process of recruiting local teachers to take part in the pilot. Plans were also made to communicate with school administrators at pilot schools and to secure permission from parents or guardians for students to participate.

Materials. The adaptation and customization process was completed over approximately six months. The resulting resource, the Bozeman Water Conservation and Stormwater Management Educator Guide, is a 45-page booklet containing not only the five activities but also maps and other teaching aides as well as pages that could be copied and distributed to students. Activities were correlated to state and federal standards.

The program’s five lessons offer some of the basics of water literacy and delve into more advanced topics specific to Bozeman’s watershed, all using Project WET’s interactive education methods. In “Seeing Bozeman’s Watershed,” students learn what a watershed is and then use maps to identify the key features of Bozeman’s Gallatin River and Bozeman Municipal watersheds. “A Year in the Gallatin River Watershed” teaches students how water flows in different seasons and at different elevations through a whole-body exercise as well as mapping and graphing work. The “Stormwater Hike” activity introduces the idea of city watersheds and explores the Bozeman stormwater distribution system by having students investigate how stormwater flows on their own school grounds. In “Sum of the Parts,” students demonstrate how stormwater runoff can eventually carry pollution into Bozeman’s waterways. “Bozeman Home Water Audit” zeroes in on home water use with and without the use of water conservation practices to encourage students to take action to conserve Bozeman’s water.

Teacher Training Process. Using a combination of material presentation and peer teaching, staff from the Montana Watercourse and Project WET trained the teachers to use the program with their upper elementary and middle school students in a series of evening workshops. Teachers were given information about how to communicate with parents about the program, how to integrate the lessons into their existing curriculum, and how to evaluate student learning. In addition to printed copies of the Bozeman Water Conservation and Stormwater Management Educator Guide, teachers received an assortment of Project WET children’s activity booklets on topics related to the Educator Guide lessons and geared toward ages eight to 12.

Schools participating in this pilot program received special recognition by the city of Bozeman, and teachers received a stipend for attending the training and completing the program.

Implementation With Students. Once trained, the teachers themselves determined the best timing for each lesson within the program. They were also responsible for securing permission from students’ parents to participate. When program lessons were scheduled, staff from Project WET, MTWC, and the city attended at least one lesson with each of the teachers to see the program in action. In one case, staff observed a fifth grade class using the “Sum of the Parts” activity to simulate how stormwater could move trash and other pollutants left on the ground from one park in Bozeman to another and eventually into the East Gallatin River, a popular recreation area for local residents. At the conclusion of the activity, students brainstormed best management practices that they could adopt—such as picking up after their pets, throwing trash into proper receptacles, and recycling—all in an effort to demonstrate how to protect Bozeman’s waterways.

In all pilot classes in both year one and year two, students were given a nine-question test of basic watershed, stormwater, and water conservation information before starting the program and after.

The Pilot’s Impact

Year One (2014–15 School Year). The first year of the Bozeman Water Conservation and Stormwater Management program pilot was implemented with

- three schools

- three teachers

- eighty-one students in the fifth and sixth grades

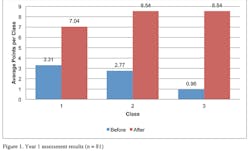

Students in the three classes improved their knowledge of an average of 5.69 points between the pre- and post-assessments, as illustrated in Figure 1.

The results indicated that the students in the three classrooms showed significantly better understanding of watersheds, stormwater, water conservation, and how individual actions can impact water following the implementation. Students’ test scores for this first pilot year jumped nearly 250%.

Educators provided real-time reactions to the content of the educational materials to Project WET and MTWC staff as well as more formal reviews after the school year had ended. In-person interviews were conducted with each of the three teachers at the beginning of the 2015–16 school year to gain insights into their experiences with the year one pilot. Comments ranged from the very specific to the more general:

- “I would advise dividing the number of beads on the hydrograph by 10.”

- “I suggest using crumpled paper and water markers to have kids trace the ridge of the mountain when learning about watersheds.”

- “This program is a great idea—especially given current awareness of droughts.”

- “I loved everything about the activities!”

- “I liked that all the materials were provided.”

- “I’d like to have a lesson about snow, since that is very relevant to Bozeman.”

- “I really loved that the curriculum is place-based. It makes it richer and more powerful because it is for Bozeman and we all care about where we live.”

As with the first year of any new program, some challenges did arise:

- Students in the pilot classes were not as familiar with local landmarks as had been assumed. One of the activities included a number of municipal parks as well as the locations of Bozeman School District 7 elementary and middle schools. Although these were meant to orient them to show how water flows downhill and into waterways, students were unsure which parks were located in what sections of Bozeman and had to learn more about the area’s geography before getting to the heart of the lesson activity.

- One teacher heard from parents who perceived that their child was being manipulated by propaganda about water conservation as a stepping stone to discussions about climate change, which they did not believe in.

- Five teachers were originally trained and given materials to be a part of the first-year pilot. Two of these five were unable to complete the program due to time constraints or other issues.

Based on the experiences of the year one pilot, Project WET and the city of Bozeman decided to make slight alterations to the materials and training process for the year two program. Given requirements that teachers must incorporate technology education into their lessons, pilot teachers recommended that the Educator Guide include specific suggestions on how to use widely available educational technology on classroom computers and tablets. In particular, teachers requested that additional activities incorporating spreadsheet exercises and the use of Google Maps be added. Two activities also got new titles based on teacher and parent feedback: “Sum of the Parts” became “Adding Up Stormwater Pollution” to better reflect the role of stormwater in the activity, and “Bozeman Home Water Audit” shifted to “Bozeman Home Water Investigation” because of the sensitivity of some parents to the idea of home water use being “audited.”

Year Two (2015–16 School Year). Year two of the Bozeman Water Conservation and Stormwater Management pilot program was implemented with more teachers, more schools, and a lot more students—almost six times as many as in year one. In total, the year two pilot impacted

- four schools

- five teachers

- 473 students in the fourth, fifth, and sixth grades

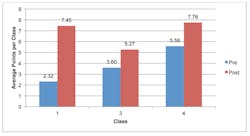

The students in the year two program showed an average improvement of 2.99 points on the nine-question assessment between the pre- and post assessments (out of nine total possible points), as shown in Figure 2.

In-person interviews have not yet been conducted with the teachers, but written evaluations again found a mixture of feedback:

- “The kids loved getting outside and being able to relate info to their school.”

- “It really made students think about water use and conservation.”

- “The activities gave great visuals and most students had a connection to the watershed.”

- “The school water investigation might be more realistic to do as a group.”

- “Having a Google Map with markers available ahead of time would be helpful.”

- “We loved ‘Stormwater Hike,’ and the GIS map of the city stormwater collection system was definitely beneficial.”

Some new challenges arose during year two. One of the fourth-grade classes hadn’t yet reached the necessary stage of proficiency with some of the required math, so the teacher had to scale back the sophistication level. On the teacher training side, the number of teachers available to recruit posed another challenge. The training workshops require a large enough group to allow for peer teaching activities, and the relatively small number of teachers at the targeted levels made interaction difficult.

Given the experiences and feedback from year two as well as information garnered from administrators with the Bozeman School District, the biggest change moving forward is that middle school, and specifically sixth grade, represents the optimum target grade level for the program.

Next Steps and Lessons Learned

Based on the success of the two-year pilot program, the partners have decided to continue the program and have embarked on the process of formally embedding the Bozeman Water Conservation and Stormwater Management program into the official Bozeman Public Schools science curriculum at the sixth grade level. Meetings on that process began recently and will continue into 2017. The challenges facing the program’s continued growth and success include the time and effort it will take to complete the curriculum approval process through district administrators, the best way to train teachers to use the program given the many competing professional development requirements that educators face, and tracking the impacts both in outputs as well as outcomes, i.e., what actions have been taken as a result of the program and what qualitative data can be gathered to show success at the school level and beyond.

While not discounting the challenges existing now, tremendous opportunities exist as well. First and foremost, the Project WET Foundation is very interested in replicating this successful model to other cities, big and small, in Montana and around the country. If that expansion to other communities happens, the development of the effort could be taken to another level by facilitating the interactions between schools in different watersheds to share their stories.

There are other expansion possibilities that aren’t necessarily geographic. Building additional educational materials, including online resources or mobile apps, could further expand learning for students. To return to the idea in the introduction of kids bringing lessons home to their parents and other adults, the program could also engage city leaders in the education and action process. Kids have much to teach adults—especially as they are the ones who will live with the consequences of the actions our leaders take today.

Stormwater utilities can learn some important ideas from this effort in Bozeman. Kyle Mehrens, Bozeman’s stormwater coordinator, notes that the pre- and post-assessments completed as part of the education process allow the Stormwater Division to acquire critical data. Like most such departments, the Stormwater Division is required to track measurable progress with the work it completes.

“It is critical that public employees make smart financial decisions on behalf of the citizens they represent,” says Mehrens. “Our work with Project WET is a fiscally responsible way to make a huge difference in our community. Project WET has exceeded our expectations. It’s clear why they are so successful at educating the world on water issues.”

Frank Greenhill, a technician with the Stormwater Division, says the partnership is benefiting water quality in Bozeman. “The data collected over the last two years confirms that the information presented is being learned and remembered,” he says. “Project WET has done a fantastic job growing our program, and I am excited to continue working with them as we transition out of the pilot stage and work toward citywide curriculum integration.”

“Public education and participation is a major component of our program, and we continuously look for effective, measurable, and economical ways to reach audiences,” concludes Mehrens. “Working with Project WET allows us to reach an often overlooked but extremely important audience year after year.”

Reference

Evans, S. M., M. E. Gill, and J. Marchant. 1996. “Schoolchildren as Educators: The Indirect Influence of Environmental Education in Schools on Parents’ Attitudes Towards the Environment.” Journal of Biological Education. 30(4): 243–48.

Acknowledgment

The authors would like to acknowledge factual contributions from the city of Bozeman in the preparation of this article.