Vegetating Ski Runs

Beautiful Lake Tahoe straddles the California-Nevada border and is situated approximately 40 minutes from Reno, NV, and a little over three hours from San Francisco. Near the north shore of Lake Tahoe, on the California side, sits the historic small town of Truckee, home of the Northstar ski resort.

In the spring of 2008, Northstar built four new ski runs and a ski lift, and Kelley Erosion Control, based in Reno, was brought in to help revegetate affected areas. Owner Kym Kelley describes the process:

“First the loggers came through with mastication of the remaining tree stumps, then we came in and broke up rocks and boulders. We didn’t want any rocks larger than about 6 inches, but we also didn’t want to disturb the subsoil, so we had to chisel down the boulders. Then the snowmaking guys came through, and we followed right behind them. The snowmaking lines were all hydroseeded, each approximately 50 feet wide and 2,000 feet long. In areas where the soil had been turned, we used soil amendments.”

Kelley utilized a Finn T-400 HydroSeeder with a 4,000-gallon tank, in addition to a smaller Finn T-90 with an 800-gallon tank, dragged by a bulldozer. “I wouldn’t use anything other than a Finn,” she reports. “These are the most popular machines, and the company takes really good care of us. Parts are shipped out promptly. We get tons of mileage out of our equipment-we use the heck out of it.” Finn offers leasing options, but Kelley owns all of her HydroSeeders.

The hydroseeding mixture she selected included:

- Biosol as a fertilizer, at 1,800 pounds per acre

- Kiwi Power, an organic complex consisting of microorganisms and enzymes, humic acid, organic wetting agents and cytokinins, and organic growth hormones, at 5 gallons per acre

- Mycorrhizae, fungi that help roots absorb nutrients, at 60 pounds per acre

- Grass seed at 22 pounds per acre

- Paper mulch at 2,000 pounds per acre

- Tackifier at 150 pounds per acre

“It took about two to three months to treat about 50 acres; it was very labor-intensive,” Kelley says. “In some areas, we were able to take some of the logged trees and produced wood chips for mulch. That was the advantage of following behind the loggers. The availability of these wood chips determined what we used for mulch. Where the chips were not available, we applied hydromulch.”

Her work began in May 2008, and she reports that little rain fell at the time, which proved advantageous. “We didn’t want too much rain, so the seed will sit dormant. Germination will take place in the spring of 2009. The tackifier should be sufficient for an active run, to keep everything in place.” She typically uses about 120 pounds per acre of tackifier, but increased this application to 150 pounds per acre.

Kelley is a big advocate of hydroseeding and sees its use increasing. “The entire industry is increasing. People are really taking the environment seriously. The “˜green’ movement is definitely more in the forefront now. Hydroseeding tends to be less expensive than other options, and it provides three important benefits: erosion control, sediment control, and dust control. So you get a big bang for the buck. One spray application solves three problems at once.”

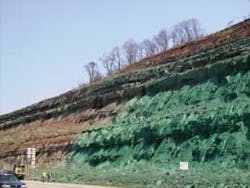

“In 15 years of working with hydraulic products, I’ve never encountered a more challenging project,” says Stephen Zwilling of Profile Products LLC in Buffalo Grove, IL. He’s referring to the 14-acre Highway 47 cut revegetation project in Parkersburg, WV.

West Virginia Highway 47 Cut

The West Virginia Highway 47 cut revegetation project in Parkersburg

“There have been many attempts over a number of years to establish vegetation here,” he explains. “When the highway was originally built and the mountainside cut, there wasn’t the erosion now found at the site.”

The problem is that this piece of mountain adjacent to the highway is very steep and very high, reaching as high as 425 feet above the pavement. In the past, the state department of transportation (DOT) had tried various options, including broadcast seeding and hydroseeding. They had considered the use of erosion control blankets, but with nearly vertical, highly eroded slopes, it was unlikely that blankets could even be installed. Building a large concrete retaining wall was another option, but its multi-million-dollar price tag effectively ruled out this hard-armor solution.

Marc S. Theisen, vice president of Erosion Control Solutions with Profile Products, explains that his firm was brought in to try to resolve the ongoing issues. He found not only that the mountainside was eroding and “very inhospitable to revegetation,” but also that access to the site was very challenging; so much so, in fact, that the state had considered the use of a helicopter in its hydroseeding efforts. Theisen explains that the overall slope of the hillside was greater than a 45-degree angle, measuring about 0.75 horizontal to 1 vertical, with certain sections even steeper.

Yet another problem popped up. Theisen and Zwilling both note that the soil in this part of the country, as in much of the eastern US, tends to be somewhat acidic, and officials at the West Virginia DOT naturally assumed that this Highway 47 cut was no exception. However, no soil sampling had been done.

“You’d be surprised,” Theisen says, “how often such projects proceed without any agronomic soil testing.

The mountainside was eroding and was very “inhospitable to revegetation.”

They’ll do all the geotechnical and sieve analysis tests to keep the engineers happy, but they often fail to conduct any agronomic testing.”

Ultimately, a soil analysis was conducted, which set off several alarms. Most shocking was the pH of the soil. Rather than being slightly acidic, the soil pH measured as high as 10, which is highly alkaline. Zwilling notes that the department had planned on adding lime-based soil amendments, thinking that perhaps the presumed acidity of the soil was contributing to the difficulty in obtaining viable vegetation.

Zwilling is not surprised that a soil sample had not previously been taken. He speaks to and works with engineering firms routinely and finds that perhaps 95% of the time, a soil test is not conducted prior to breaking ground. “But these are very inexpensive,” he says, “costing perhaps $50 or less, rising to around $200 if immediate or more extensive analyses are needed. When I tell them the low cost of soil tests, and note that pH is the second-most-critical consideration (after water) for ensuring effective nutrient uptake and successful establishment of vegetation, I find that they are appreciative, and many people are changing their ways. For example, both the West Virginia DOT and the South Carolina DOT now require that soil be tested.”

The Adirondack slopes in Warren County, NY

Zwilling emphasizes, “When plants are trying to establish themselves, everything needs to be in balance so immature plants can establish their root systems and grow.” And the pH level is an important part of the equation. Ideally, soil pH should fall within a range of 6.3 to 7.3 for healthy plant growth.

Theisen notes that once the pH problem was identified, he knew that it had to be lowered substantially. Another question that remained was what kind of seed mix to use. Drawing on the combined experience of the West Virginia DOT; the Department of Natural Resources (with its experience in difficult mine reclamation projects); Profile Products’ in-house agronomists; and its local contractor, Penn Line Service, an interesting seed mix was developed. Several different seed types were utilized, including orchard grass, birdsfoot trefoil, redtop grass, switchgrass, perennial rye, and alsike clover. Perhaps the most surprising part of the mix, however, was the inclusion of Bermuda grass.

Bermuda grass is rarely used in that part of the country, Theisen explains, because it favors a warmer climate. It is also not often used on such steep slopes. Zwilling made the call to include Bermuda grass, however, because at the time of application, they were entering a hotter part of the year and Bermuda is more drought-resistant than many other grasses. Zwilling was concerned that there might not be sufficient rainfall to nurture the growth of the predominantly cool-season seed mix. He also had another reason to use Bermuda grass. “It sends out runners and creeps all over the place,” he says. “Plus, it fills in areas. If I had to do the project all over again, I’d use an even higher proportion of Bermuda grass in the mix.” Theisen adds that the Bermuda grass is now gradually cascading down the cliffs and creating an erosion-resistant root mass.

Another issue that frequently arises, according to Zwilling, is the organic content in the soil, which typically

Hoses were used to hydroseed the Piceance Basin in western Colorado.

comes from decomposed plant material. “You need at least 2 to 3% organic matter in the soil for plants to thrive. This is typically, but not always, found in most topsoil. Farmers know that if you have good topsoil, you have good crops.” He adds, “If the organic matter content is too low, you need to amend the soil. For example, you can bring in topsoil or compost. In addition, we now have new additives that can be mixed into the hydraulic slurry to significantly increase the organic composition.”

In this specific project, the organic content was about 4%, but certain areas were devoid of organic content. “You can apply Flexterra FGM over shale,” Zwilling explains, “but you need some soil present in order to achieve plant growth. In this project, the soil was crummy, there were lots of rocks, the pH was out of balance, and there were really steep slopes. It was hard to get infiltration, since with slopes so steep, everything just runs off.”

Because of these problems and the lack of viable alternatives, the decision was made to proceed with a site-specific mode of hydroseeding, but another problem had to be addressed. Typical hydroseeding machines can spray a distance of nearly 200 feet, but the slopes involved ranged from about 150 feet high to more than 400 feet high. For such distances, Zwilling says, “You need to apply the mixture aerially or use a hose. We chose to use a hose and ran it up the slope. The workers would climb up the hillside, and the machine was powerful enough to spray through the hose.” The Pennsylvania-based contractor, Penn Line Service, used a 3,300-gallon Finn HydroSeeder for the application.

The difficult project had to be completed in steps. Initially, elemental sulfur, powdered iron sulfate, and gypsum were hydraulically applied to reduce the soil pH, and this mixture required time to activate. Penn Line waited approximately two weeks before proceeding with the actual hydroseeding. In addition, a combination of Super-Bio microbes, Profile JumpStart 5, and a 15-30-5 fertilizer was applied to build an effective organic base for seed establishment.

Zwilling points out that, partly as a result of the difficulties encountered in this project, a new soil neutralizer has been developed-Aqua-pHix. It is intended for soil with a pH greater than about 7.3 and can be applied to buffer the soil. In contrast to this Highway 47 project in which two weeks were needed to alter the pH, with Aqua-pHix, “You simply pretreat with it, allow 1 to 2 hours’ time, then apply the mulch/seed mix. It essentially adjusts the pH in just a few days with the effect lasting for perhaps 18 to 20 weeks,” he explains. A related soil conditioner from Profile Products, NeutraLime, is available in cases where the pH is too low, less than about 6.3.

Another important decision in the project was the selection of appropriate mulch. Zwilling explains that on simpler projects, a basic wood and paper hydraulic mulch may be sufficient. “These are OK for limited erosion control, they’re inexpensive, and they work well for flat areas.” But for this project, a different formulation was needed.

Zwilling elected to use Flexterra FGM, a flexible growth medium that immediately bonds to the soil. Flexterra combines “thermally refined” wood fibers with crimped manmade fibers and other additives to produce an interlocking matrix with water-absorbing cavities that enhance germination and reduce soil loss.

“It maintains its strength even in wet conditions,” Zwilling says. “It will stick to a vertical slope-it locks on. You spray it on, it sets up and cures, and soil particles don’t move. Flexterra retains up to 1,500% of its weight in moisture and is the only hydraulically applied product that doesn’t require an extensive curing time. If it rains, or something blows in, Flexterra will stay in place. Most other products would just wash away.”

Flexterra, which comes in 50-pound bags, was applied at a rate of 4,000 pounds per acre on these challenging slopes. “We were essentially painting on a blanket over the rock and soil,” says Zwilling. “But we applied the hydroseeding mixture in stages, in case of bad weather.” Although this product resists washing off better than others, in a significant rain event, some of the product will ultimately wash away. He stresses that Flexterra is not designed for areas of concentrated water flow, as in channels or roadside ditches. Its primary use is for slope stabilization.

He adds that paddle-agitation hydroseeding machines are needed in order to use spray-on blanket products to keep the highly viscous slurries in suspension. A jet agitation unit is unable to handle thick slurry, he explains, and Flexterra is a very thick mixture. He also prefers bigger hydroseeding machines on large projects, because “they have more power, more room for the mix, can cover a larger area, and are simply more efficient. You don’t need to reload the tank as much.”

The initial proposal for the Highway 47 project was submitted in April 2006, but because of funding and timing issues, work didn’t begin until May 2007. From the start, everyone involved understood that there were some inherent limitations. “Nothing will grow on bare rock, so the area will never be fully vegetated,” Zwilling says. But today he is proud to be able to claim, “Where there’s soil, there’s now vegetation. Nothing had ever grown here before. Rockslides cannot be totally prevented, but the risk of a dangerous rockslide has now been minimized.” Theisen adds, “It doesn’t look like a golf course-we knew that it wouldn’t-but the amount of cover is significantly greater than before, and it is expanding, and the soil is stabilizing.”

Eroding Adirondack Slopes

In July 2008, the New York’s Warren County Soil and Water Conservation District took action to correct a problem that had been lingering for many years. Within the district lies the town of Warrensburg, NY, located within the rocky terrain of the Adirondack Parkway. Slopes had long been eroding into the Upper Hudson River watershed, which is a pristine watershed utilized for drinking water and recreation. For years, in order to save money, Warren County had been using a standard guar tackifier, along with fiber, to try to stabilize the area’s slopes. Results were less than optimal, and finally, the Soil and Water Conservation District, tired of repeatedly having to go in and reseed as a result of erosion from heavy rainfalls, took action.

After hydroseeding with organic fertilizer and a guar tackifier, a modified-matrix

flexible growth medium mulch is used at the Colorado site.

The Bakersfield, CA, company Terra Novo had previously discussed with the district the use of its erosion control product EarthGuard Fiber Matrix. The county decided to try EarthGuard on a test patch of slope to compare with the guar tackifier already in use.

Brian Foster of Terra Novo describes EarthGuard as a polymer stabilizer fiber matrix, which is a spray-on erosion control product “designed to work directly with soil to maintain its stability by both preserving existing soil structure and flocculating fine sediment being dislodged by stormwater or wind. Unlike bonded fiber matrices and other copolymers, it doesn’t harden to create a false barrier, which prevents water from entering the soil and seeds from germinating.” EarthGuard can be applied by itself for rapid dust and erosion control, or with a seed mix to achieve quick vegetation in difficult environments.

In the test patch, the EarthGuard was applied next to the guar/fiber mixture on a rocky and slightly eroded slope. No special slope preparation was undertaken. The district used a Finn T-90 HydroSeeder to spray a combination of seed, mulch, and water onto the bare soil, and Foster reports that within 2 to 3 weeks, new grass was emerging to stabilize the soil. For steep slopes, such as those encountered in Warrensburg, the recommended application is 10 gallons of EarthGuard, teamed with 3,000 pounds of paper mulch, per acre. A flatter environment may be successfully treated with half of these amounts.

The Soil and Water Conservation District was impressed with the results. The day following the EarthGuard application, approximately 4 inches of rain fell, with a total of some 10.5 inches of rain over a 19-day period. Foster notes that the EarthGuard Fiber Matrix provided effective erosion control, in addition to the grass already sprouting. On the guar/fiber side, there was less plant growth and significant erosion.

Within two months following application, a whopping 20 inches of rain had fallen. The slopes treated with EarthGuard remained stabilized and had achieved full seasonal growth. On the other hand, the guar/fiber slopes suffered significant damage and will need to be regraded and reseeded.

According to Foster, “Standard tackifiers-such as guar, PAM, and psyllium-do not have the strength to stabilize slopes through long and heavy rain events over an extended period of time. Their effectiveness typically erodes away before a seed is able to successfully germinate and establish a root mass and soil cover sufficient to provide effective erosion control on its own.”

Jim Lieberum, water resources specialist with the Warren County Soil and Water Conservation District, says, “I was very impressed with how well EarthGuard held up with all the rain we received the day after application. It saved us time and money not having to revisit the slope.”

Oil and Gas Drilling Reclamation

Western Colorado is oil and gas country, and the region’s Piceance (pronounced PEE-awnts) Basin may well contain the nation’s largest natural gas reserve. A decade ago, it was estimated that the 6,000-square-mile Piceance Basin may contain 30 trillion cubic feet of natural gas, but some current estimates reach as high as 300 trillion cubic feet.

The town of Parachute, CO, lies in the approximate epicenter of the basin and that’s where Colby Reid, reclamation manager for Western States Reclamation, has been working lately.

With such mammoth reserves, the basin is home to thousands of wells, with hundreds added annually. It is Reid’s job to revegetate the area surrounding new wells. It’s generally a two-step process. “First,” he explains, “the gas company will lay down the road. As soon as the road is pushed in, we’re there to seed the topsoil and the roadside. Then, after the drilling pad is put in-hole drilled and piping put in-we’re in the next day. The gas company makes the pad a bit smaller and contours it, then we go in and do the final seeding.”

These “pads” and their surrounding area total about 5 to 7 acres each and are located on an assortment of private land, Bureau of Land Management land, and Forest Service land. They range from an elevation of 5,000 feet to as high as 9,000 feet.

Reid estimates that about 70% of his revegetation efforts in this area involve hydroseeding, applying varying seed mixes of grasses and shrubs. He treats the area around the drilling pads as well as the roads leading into the pads; the work is not easy. “This is a harsh environment,” he says, “and it typically takes about a year to get any vegetation established. We have to contend with rain, (or lack thereof) and wind, and weed control as well.” He is in the area frequently because of his extensive reclamation work and is able to periodically check on previous applications, but reports little need for post-treatment touch-up work.

His applications occur in two phases. Initially, he hydroseeds with organic fertilizer and a guar tackifier together with the seed load. Then, about 24 hours later, he follows this with a modified-matrix flexible growth medium mulch. He uses 50-pound bags of Flexterra, applying about 3,500 pounds per acre, using two coats from two different directions to avoid a “shadowing” effect. He applies this mulch well after seeding, he explains, because “out West, it is too dry to combine all of this in a single hydroseeding application. The seed would just get caught up in the mulch.”

Reid utilizes two types of hydroseeding machines. He has a Finn 3,300-gallon HydroSeeder and two new Finn Titan 4,000-gallon units, all of which use paddle agitation. “Jet agitation is more for smaller machines,” he notes.

He uses hydroseeding cannons to spray up to about 200 feet, but beyond this, he has to use hoses, often 200 to 300 feet in length. “We do a lot of hose work,” he explains.

Although hydroseeding is his most common treatment of choice, he also uses erosion control blankets, employs a fair amount of drill seeding, and, occasionally, uses straw/hay mulch rather than a hydromulch slurry. “If the terrain is flat enough, I’ll drill-seed,” he says. “However, if it is too steep or too remote, I’ll hydroseed.”

In contrast to many other revegetation projects around the country, Reid finds that in most of the areas he works, a soil analysis has been done. The pH tends to come up a little alkaline, but not enough to require soil amendments.

Because of the demanding environment in which he works, Reid finds that his hydroseeding work remains pretty stable, perhaps increasing a bit due to new wells being drilled.