Applying sustainable groundwater management: A sediment basin retrofit for enhanced recharge

Key Highlights

- California's San Joaquin Valley faces critical groundwater overdraft due to prolonged droughts and land subsidence, necessitating innovative recharge solutions.

- Passive infiltration retrofit projects, like the IRIS system at Leaky Acres, can dramatically increase basin infiltration rates without extensive construction or energy use.

- Long-term data and monitoring are essential to validate performance improvements and guide scalable, low-impact groundwater recharge strategies.

Lessons Learned and Best Practices

- Use long-term datasets to establish reliable performance baselines

- Prioritize upgrades to existing basins before constructing new ones

- Favor passive, low-disturbance methods when native soils can be leveraged

- Evaluate water levels volumetrically, not just through point measurements

- Plan for an acclimation period in passive recharge systems, typically 4-6 months

- Scale through replication — similar sedimentation basins can be upgraded using the same approach

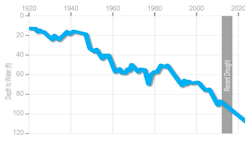

By 2017, the San Joaquin Valley was deep into one of the most severe droughts in California’s modern record. Despite aggressive water conservation policies, groundwater levels in the region continued their century-long decline of one-to-two foot per year, accelerating toward the aquifer's minimum threshold, where an "undesirable result" may occur (North Kings Groundwater Sustainability Agency 2022). Some consequences were already evident, including dry wells and satellite measurements that documented widespread and continued land subsidence across the valley (NASA JPL 2017). This long-term result of over-pumping had already permanently eliminated as much as 606,000 acre-feet of aquifer storage (Smith, et al. 2017).

For Fresno, a half-million-person city within the critically overdrafted Kings Subbasin, finding new ways to capture and store water underground became critical to ensuring long-term water security. Ideal projects would expand recharge capacity without large capital investment or new land acquisition.

One such project was the retrofit of a de-siltation pond at the Leaky Acres Recharge Complex, where groundwater infiltration improved ninefold. The effort demonstrates how existing stormwater infrastructure can be transformed into productive recharge assets.

Background

California’s water challenges increasingly reflect a pattern predicted by climatologists for decades: droughts are lasting longer, and wet years are becoming more intense (IPCC 2007). As hydrologic variability grows, water agencies are relying more heavily on managed aquifer recharge (MAR) to capture storm flows, divert surplus canal water into recharge basins, and store it underground for use in dry periods.

This shift was given legal weight in the Sustainable Groundwater Management Act of 2014 (SGMA 2014), which requires all high- and medium-priority basins to balance groundwater pumping and recharge. In chronically depleted basins such as the Kings Subbasin, Groundwater Sustainability Agencies (GSAs) must achieve sustainability by 2040 through a combination of recharge projects, pumping reductions and operational changes.

Long-term monitoring data from the Kings Subbasin illustrates why groundwater recharge is essential. Hydrographs spanning more than a century show a persistent downward trend, with water levels dropping by more than a foot each year (Figure 1). Recent dry periods accelerated the decline and, in some areas, falling water levels contributed to measurable land subsidence, described as "the greatest human alteration of the Earth’s surface“(Borchers 2014), and reducing of the aquifer's storage capacity. From these trends, the need to improve groundwater recharge became urgent.

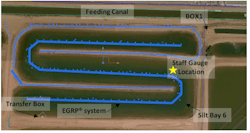

With each GSA in the basin responsible for projects to correct the overdraft by 100% in 20 years, the city of Fresno evaluated opportunities within its existing stormwater infrastructure. At the Leaky Acres facility, a sedimentation basin known as Silt Bay 6 had the footprint, hydraulic access and location needed to contribute meaningfully to the city's recharge plan (Figure 2). Recognizing this, the city initiated a retrofit strategy aimed at recovering the basin’s infiltration potential without large-scale construction or disruption.

Passive infiltration retrofit

Concept and design approach

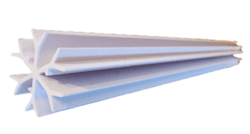

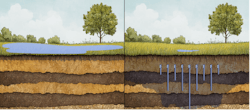

The retrofit focused on transforming Silt Bay 6 from an underperforming four-acre sedimentation cell into a productive recharge basin using Parjana’s IRIS (former EGRP) system (Figure 3), a passive subsurface technology designed to enhance vertical and lateral water movement through undisturbed native soils (Figure 4). Based on seven years of water level data, the project goal was to quadruple the basin’s previous infiltration rate. Relying on natural physical forces such as gravity, capillarity, osmotic pressure, and surface tension to draw water downward and outward, the IRIS system facilitates deeper and more distributed infiltration through heterogeneous soil layers (Figures).

Retrofit installation

A total of 3,195 IRIS devices were installed across the basin floor, creating a dense subsurface network of passive infiltration conduits. Devices were installed at depths ranging from 5 to 40 feet using small diameter (1.75–2.5-inch) compression-auger boreholes. Each device was installed using an interference-fit method that preserved soil structure and prevented preferential flow paths. All devices were capped at 2 feet to avoid direct vertical channeling and to promote natural soil filtration. In total, the retrofit added 43,980 linear feet of passive infiltration conduit beneath the basin.

Installation was completed over a 31-day period using three drilling rigs operating in parallel. Survey control minimized disturbance to the basin floor, and a staged approach was used to ensure structural integrity during drilling. Lower sections were installed first, followed by gradual filling of the basin to stabilize sidewalls. Additional devices were installed in the upper sections once sufficient water depth provided wall support.

The completed configuration converted Silt Bay 6 into a distributed field of passive infiltration nodes, requiring no pumps, energy inputs, or major structural modifications. This low-maintenance design allowed the existing basin footprint to function as a significantly more productive recharge asset without expanding facility boundaries or altering surface infrastructure (Figures 5 and 6) .

Performance monitoring

A two-year monitoring program was implemented to evaluate infiltration performance after retrofit. The approach combined staff-gauge measurements, 3D basin modeling, rainfall and evaporation data, and flowmeter readings between Silt Bay 6 and the adjacent basin.

Seven years of staff-gauge records (2011–2018) were used to establish the pre-retrofit infiltration baseline. To interpret changes in basin water levels accurately, the team paired daily staff-gauge readings with a 3D storage-volume model that converted water elevations into volumetric changes.

These measurements were cross-checked against rainfall data from the NOAA Fresno Yosemite Airport station and evaporation data from UC IPM’s Fresno site to account for atmospheric inputs and losses. Flowmeter readings quantified any transfers between Silt Bay 6 and the adjacent basin, allowing the team to separate internal routing from true infiltration.

Finally, historical analysis of closed-valve conditions confirmed that natural percolation at the site does not exceed 0.07 feet per day, providing a baseline threshold for comparison. Together, these datasets allowed the team to isolate subsurface infiltration from rainfall, evaporation, and inter-bay routing.

Results

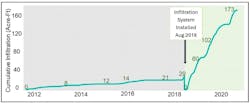

The retrofit ultimately exceeded performance expectations by more than double. Following installation, average infiltration increased from 13,800 gallons per day to 124,000 gallons per day, representing a ninefold improvement, well over the 400% goal. The system responded quickly, demonstrating measurable gains within the first few weeks and reaching full stabilization after roughly 140 days once the subsurface acclimated.

These increases in infiltration capacity translated directly into greater recharge volume. Over the 26-month monitoring period, the basin infiltrated 173 acre-feet of water, compared to just 29 acre-feet over the previous seven years. On a normalized basis, monthly infiltration increased 18× from 0.36 to 6.65 acre-feet per month (Figure 7).

The results were validated through continuous monitoring corrected for rainfall, evaporation and inter-bay water transfers, providing confidence that the gains reflected true changes in subsurface performance.

Conclusion

The Silt Bay 6 retrofit highlights a practical path forward for basins operating under SGMA and similar groundwater requirements. Many communities lack the land, funding or time to construct large new recharge facilities, but meaningful gains can still be achieved by upgrading existing stormwater assets.

By converting an underperforming sedimentation basin into a high-functioning recharge cell, the project offers a scalable, low-disturbance approach for agencies seeking rapid, cost-effective recharge improvements. With transparent monitoring and results that can be validated quickly, Silt Bay 6 shows that progress toward groundwater sustainability does not always require major new infrastructure — it can begin by optimizing what is already in place.

References

Borchers, J. W., et al. Land Subsidence from Groundwater Use in California. Sacramento: California Water Foundation, 2014. https://cawaterlibrary.net/wp-content/uploads/2017/04/1397858208-SUBSIDENCEFULLREPORT_FINAL.pdf

California Department of Water Resources. SGMA Portal – San Joaquin Valley – Kings Subbasin (No. 5-022.08). Sacramento: California Natural Resources Agency. https://sgma.water.ca.gov/portal/gsp/preview/24

California Department of Water Resources (DWR). 2014. Sustainable Groundwater Management Act: Summary Document. Sacramento, CA. Accessed November 11, 2025. https://water.ca.gov/Programs/Groundwater-Management/SGMA-Groundwater-Management

Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC). Climate Change 2007: The Physical Science Basis. Contribution of Working Group I to the Fourth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2007.

NASA Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL). 2017. NASA Data Show California’s San Joaquin Valley Still Sinking. February 28, 2017. https://www.jpl.nasa.gov/news/nasa-data-show-californias-san-joaquin-valley-still-sinking. NOAA National Centers for Environmental Information (NCEI). 2014. “Fresno Yosemite International Airport Weather Data.”

NOAA National Centers for Environmental Information. Fresno Yosemite International Airport Weather Station Data. National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration.

(Referenced for rainfall observations.)

North Kings Groundwater Sustainability Agency. 2022. Groundwater Sustainability Plan. Adopted November 21, 2019; revised and adopted June 13, 2022. Fresno, CA.

Smith, R. G., R. Knight, J. Chen, J. A. Reeves, H. A. Zebker, T. Farr, and Z. Liu. 2017.

“Estimating the Permanent Loss of Groundwater Storage in the Southern San Joaquin Valley, California.” Water Resources Research 53 (3): 2133–2148. https://doi.org/10.1002/2016WR019861.

UC Integrated Pest Management Program (UC IPM). 2018. Fresno CIMIS Station Evaporation Records. University of California Agriculture and Natural Resources. https://ipm.ucanr.edu/weather/#gsc.tab=0

About the Author

Douglas Davis

Douglas Davis is an environmental remediation professional with 30+ years of experience designing groundwater investigation and treatment strategies. He operates Davis Allen, LLC, providing technical content and consulting services for water-sector and remediation projects across the U.S.